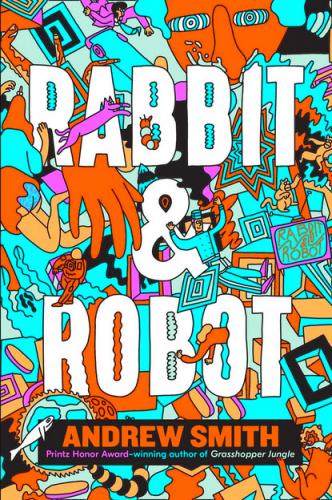

“There was a time when people theorized the moon was made of cheese.

Up here on the Tennessee, though, I can see it is more likely made of ash. Probably all the ashes from all the fires of all our pasts, forever and ever.

And I can turn and, in one direction, see the surface of this enormous cratered ashball as it skims below us like a moving sidewalk; and, in the other, the smoke-shrouded Earth—our lost home—burning itself out, exhaling ash one last time.

Among the enterprises that made my father one of the five wealthiest people in America (and those ventures included a television program called Rabbit & Robot, as well as a line of lunar cruise ships like the one Billy and I were trapped on) is transporting deceased loved ones— not their ashes, but their actual bodies—to the surface of the moon, where they are laid out like vigilant sentinels, eternally gazing down, or up, or wherever, at the planet of their origin. They never decay, never change. Billy and I can see the bodies every time the Tennessee passes above Mare Fecunditatis, which oddly enough means “Sea of Fertility.”

There are more than thirteen thousand fertile and dead sentinels floating there atop that sea of ash, staring down at everything that had come before them, and everything that came after.

They just lie there, dressed in their outfit of unquestioned permanence—military uniforms or perfect white smocks, every last dead and fertile one of them.

Billy Hinman and I are trapped inside a moon to our moon called the Tennessee.

Because Billy Hinman and I nicked a fucking lunar cruise ship that belongs to my dad.

Well, to be honest, it was kind of an accident. We didn’t mean to steal it, but it’s ours now, no question about it.

It kind of just fell into our hands, you could say.

And we are at the end of everything.

So, let me back up a bit.

Here are some of the things Billy Hinman and I have never done: At sixteen years of age, we have never attended school like other kids. And we also have never seen my father’s television program, Rabbit & Robot, which, like school, is only for other kids—definitely not for Billy and me.

And Billy Hinman, who never lied to me, has also never taken Woz, which is something they only give to other kids, to help them learn, so they can become proper bonks or coders, to help them “level down” when watching Rabbit & Robot.

Billy never took it, but I am an addict.

It does not embarrass me to admit my addiction to Woz. It’s about the same thing as admitting my feet are size fourteen, and that I have a painfully acute sense of smell: all true, all true. The drug became the glue that held me together, even if the source of my cohesion was, according to my caretaker, Rowan, destined to kill me.

This is why Billy and Rowan concocted the scheme to get me up to the Tennessee.

Their plan ended up saving—and condemning—all of us.

Cager Messer hears me.

Sometimes when he wakes up in the mornings—no, let’s be honest, it’s more like the afternoon, and frequently it’s evening—he says he feels good and strong, and his head is clear, and he thinks he’s not going to smoke or snort or suck down the worm, and I tell him, Cager, who are you fooling? I’ll tell you who you’re not fooling: all of creation minus one, kid.

The kid listens to me, but only because I never tell him what to do. Maybe “listens” is the wrong boy word. He hears me. Yeah, that’s what he does.

He hears me.

Which is an unbalanced social dynamic, you might say. Right? I’ve got ears. Look at me. I hear him. I know what he wants; what he isn’t getting; what he will never get; how he’s passively letting that monster-size ball roll down the hill. Gravity, take control, because Christ knows the kid doesn’t want to.

I am the Worm.

There was an episode of his father’s program, Rabbit & Robot, titled “I Am the Worm.”

Oddly prophetic, that one.

I need a cigarette, and I don’t even smoke. Whenever I ask Cager to bring me some cigarettes, he laughs and tells me I can’t smoke. So I say, fine, then bring me a gin and tonic.

In the episode called “I Am the Worm,” there are these blue space creatures who can turn themselves into anything they want to be—alligators, Abraham Lincolns (Or is it Abrahams Lincoln? This is why I need a cigarette), Phillips-head screwdrivers, frying pans, whatever—and they send out this little blue worm, wriggling through the solar system, and it ends up crawling up inside Mooney’s nose.

The worm, not the solar system.

Mooney is one of the main characters—the robot.

The worm that went up his nose reprogrammed him and made him go insane.

Bad things like that happen to Mooney in practically every episode.

Formula.

The “Rabbit,” who doesn’t really have a name, is a bonk—a soldier who’s come back from one or three, or eighteen, wars. He’s insane too.

It’s a lot of fun.

And Cager is not allowed to watch it.

Mr. Messer doesn’t want the worm to crawl up his son’s nose.

Cager Messer’s List of Things He’s Never Done

There are things that your friends will do for you that you just don’t have the guts to do for yourself.

Because, let’s face it: Cager Messer— me— I was a messed-up drug addict who had one foot—and probably most of the rest of my body too—in the grave by the time other guys were stressing over getting driver’s licenses, and losing or not losing their virginity.

Most people who were allowed to have an opinion on guys like Billy and me would conclude that I was a loser, and that we were both spoiled pieces of shit.

But Billy Hinman was my best friend. I know that now.

He saved me.

Unfortunately, saving me resulted in things no one could ever have foreseen.

Because Billy Hinman and I nicked a fucking cruise ship.

Billy stared out the window as we drifted away on the R&RGG transpod, sad and bleary-eyed. Billy was terrified of flying.

He said, “Good-bye, California. Have a happy Crambox, Mrs. Jordan.”

It was two days before Christmas; two days before Billy Hinman and I would find ourselves trapped on the Tennessee.

It was also my sixteenth birthday.

Happy birthday to me!

Billy Hinman kept no secrets from me. He and Mrs. Jordan—our friend Paula’s mother—had been having sex since Billy was just fifteen years old.

Of course I was jealous, in a sickening kind of way. What sixteen-year-old virgin guy wouldn’t be jealous of a best friend who had actual sex as often as Billy Hinman did? He had sex with just about everyone.

But