She touched her gloved hands to her heated cheeks. How perfectly lovely it was to be in love and to know that she was loved in return. When she came back to London on the arm of her husband, glowing with happiness, Papa would have no option but to acknowledge that Cordelia, and not her father, knew what was best for her. A month, perhaps three, if they made their marriage trip to the Continent. Rome. Venice. And Paris of course, for she would need new gowns, having been forced to leave most of her coming-out wardrobe at home.

‘Six months at most,’ she said dreamily, ‘and then I shall return, the Prodigal Daughter, and Papa shall be forced to kill the fatted calf.’ On that most satisfying image, Cordelia closed her mind to the troubles she was leaving behind her, and turned instead to the night of passion which lay ahead.

Chapter One

Cavendish Square, London—spring 1837

Though he wore the familiar livery, the footman who opened the door was a stranger to her. The name inscribed on her visiting card would mean nothing to him, so she did not place it on the silver salver he held out— The same one as had always been used, she noted. ‘Please inform Lord Armstrong that Lady Cordelia is here,’ she said. ‘He is expecting me.’

The startled look the servant gave her informed her that he knew her by reputation if nothing else, but he had been trained well, and quickly assumed an indifferent mask. Cordelia had no doubt, however, that she would be the topic of the day in the servants’ hall, and that every inch of her appearance would be recounted within minutes of her arrival.

The marbled hallway had changed surprisingly little in the nine years since she had last been here, but instead of ascending the grand central staircase that led to the formal drawing room where visitors were received, Cordelia was ushered through a door directly off the reception area. The book room. A choice of venue which spoke volumes.

‘I shall inform his lordship of your arrival.’

The door closed behind the footman with a soft click, leaving Cordelia alone, suddenly and quite unexpectedly shaking with nerves. The walnut desk before her was as imposing as ever. Behind it, the leatherbound chair held the indent of her father’s body. In front of it, as ever, two wooden chairs whose seats, she knew from old, placed the person who took them at a lower level than the man behind the desk. The scent of beeswax polish mingled in the air with the slightly musty smell from the books and ledgers which lined the cases on the walls. From the empty grate came the faint trace of ash. No fire burned, though there was a nip in the spring air. Another trick of her father’s. Lord Armstrong never felt the cold—or at least, that was the impression he liked to give.

Nine years. She would be thirty next birthday, and yet this room made her feel like a child waiting to be scolded. There was a similar room at Killellan Manor, where she and her sisters had been reprimanded and instructed in their duties as motherless daughters of an ambitious diplomat and peer of the realm.

Memories assailed her, things she had not thought of in years, of the pranks they had played, and the games. In the days before Celia married, they had been a tight-knit group. She had forgotten how close, or perhaps she had not allowed herself to remember, in the Bella years. She smiled to herself, remembering now. Unlike Cressie, who had always been too confrontational, or Caro, who had always been the dutiful sister, Cordelia’s strategy had been to give the appearance of compliance while going her own way. It had worked more often than it had failed. Rarely had her father perceived her to be the ringleader—that honour fell to poor Cressie. Cordelia had thought herself a master manipulator by the time she arrived in London for the Season. She had been so naive, thinking that her father was the only man in her orbit with a game to play.

The clock ticking relentlessly on the mantel showed her that she had been standing before the desk for almost fifteen minutes. Another of her father’s favourite ruses, to keep his minions waiting, ensuring that they understood their relative unimportance. She felt quite sick. Her stomach wasn’t full of butterflies but something far more malicious. Hornets? Too stingy. Toads? Snakes? Too slimy. Cicadas? She shuddered. Revolting things.

She checked the time on the little gold watch which was pinned to the belt of her carriage dress. By her reckoning, her dear father would keep her at least another ten minutes. Not quite the full half-hour. She would be better occupied preparing herself for the ordeal that lay ahead than making herself ill.

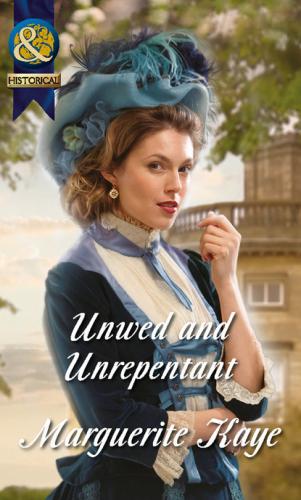

For a start, she should not be caught standing here like a penitent schoolgirl. Cordelia peeled off her gloves and laid them on the polished surface of the desk. Her fringed paisley shawl she folded neatly over the back of one of the wooden chairs. The high-crowned bonnet she had purchased, as she did most of her clothes, in Paris, was next. The wide brim was trimmed with knife-pleated silk the same royal blue as her carriage gown, a colour she favoured, for not only did it suit her, it gave her a deceptive air of severity which she liked to cultivate simply because contradictions had always amused her. The expensive bonnet joined her shawl on the chair. Pulling out a hand mirror from her beaded reticule, Cordelia shook out the curls which had taken the maid she had hired an age to achieve with the hot tongs. Far more elaborate than the style she normally favoured, her coiffure, with its centre parting and top knot, was the height of fashion and, in her opinion, the height of discomfort, but it added to her confidence, and that was, she admitted unwillingly to herself, in need of as much boosting as she could manage.

A quick mental check of the latest statement from her bank and an inventory of her stocks helped. The knowledge that her father could have no inkling of either made her smile and calmed the roiling in her stomach a little. She had no need to read the missive which had been his reply to her own request for an interview, but she did anyway, for those curt lines were a salient reminder that despite all her sisters’ assertions, her father had not changed. She would need every ounce of her resolution and backbone if she was to have any chance of succeeding.

I have granted this interview in the hope that sufficient time has passed for you to have regretted your gross misdemeanour, and for mature reflection to have inculcated in you the sense of duty which was previously sadly lacking. While the pain of your wilful disobedience must always pierce my heart, I have concluded that my own paternal duty requires me to permit you a hearing.

Your self-enforced exile has wounded others than myself. Your brothers scarce recall you. Your youngest sister has never met you. You should be aware too, that my own sister, your aunt Sophia, has been made decrepit by the passing years and has likely very few left to her on this earth.

Sincere contrition and unquestioning obedience in the future will restore you to the bosom of your injured family. If you come to Cavendish Square in any other frame of mind, your journey will have been pointless. On this understanding, you may arrange a time convenient to me with my secretary.

Yours etc.

Cordelia curled her lip at the reference to his heart, which she was fairly certain her father did not possess. Not that it precluded him tugging on the heartstrings of others. He knew her rather too well. The stories Caro shared with her, of their half-brothers and half-sister, were bittersweet. She had missed so much of their youth already that she would be a stranger to them. She even harboured a desire to become reacquainted with Bella, whose many foibles and viciousness of temperament she thought she understood rather more— For who would not be twisted by the simple fact of being married to one such as the great Lord Armstrong? Her feelings for Lady Sophia were both simpler and more complex, for while she had wronged her aunt, she could not help feeling that her aunt had wronged her too. And as to her father...

Cordelia folding the letter into a very small square and stuffed it back into her reticule. Neither salutation nor signature. He thought he was summoning an impoverished and contrite dependant. She wondered what penance he had in mind for her, and wondered, with some trepidation, how he would react when he discovered her neither contrite nor in need of financial support, but set upon reparation. In her father’s eyes, she had committed a heinous crime. His punishment had been extreme and it had taken Cordelia, her own fiercest critic,