‘Oh, her! Well, she’s apparently known as a princess, according to the maid, so she’ll certainly regard you as an inferior, Quintus. Very high status.’

‘Hmm! Does she understand our tongue, sir?’

‘So far, we haven’t had a word from her in any tongue, but I think she has a fair understanding of what’s being said. You can take her along as your slave, if you wish, or you may prefer to sell her to a merchant when she’s fulfilled her purpose. It’s up to you. You’d get a good price. She’ll have knowledge of cures and such. These tribal women often do, you know. She might even be quite useful to you, but just get her away from here. Far away.’

Quintus was puzzled. Where was the catch? There had to be one. ‘Would she be of no use to the Lady Julia Domna?’ he said, grasping at straws.

‘No,’ said Severus, irritably. ‘None at all.’

‘Does she ride, sir?’

The frown disappeared as the Emperor passed the scroll to Quintus and scratched into his curling beard. His white bushy brows, stark against the dark skin, lifted and lowered in time to the opening and closing of his mouth; Quintus saw that he’d been about to say something else about the captive before thinking better of it. He began to shuffle through a pile of scrolls, quickly losing interest. ‘On that score I have no suggestions to offer,’ he said, callously. ‘You may have to drag her there by the hair. Have you ever had the pleasure of trying to make one of these tribal women do something they don’t want to?’

‘No, sir. Not yet.’

‘Well, then, I have high hopes of you, lad. If a Tribune of equestrian rank can’t do it, I shall eat one of my socks.’

‘Only one, sir?’

Severus kept on shuffling. ‘Only one.’ He smiled. ‘Get somebody to take you down there. And don’t let me hear the rumpus.’

Quintus bowed. ‘Do we know her name, sir?’

The Emperor looked up with an unusually blank stare. ‘Damned if I know,’ he said. ‘See if the maid will tell you.’

No matter what standard of accommodation the captive had been given, it would not have found favour with her, for the heavy door was locked, confining her to four walls and depriving her of every Brigantian woman’s right: freedom. The room was, in fact, generous as prisons go, plastered walls, red-tiled floor, a barred window above head height, a low wooden sleeping-bench with a few blankets. That was all, apart from heaps of broken earthenware in the corners and one whole pottery beaker towards which one skinny arm was waving in the hope of attracting attention.

‘Please,’ a faint voice whispered. ‘Please?’

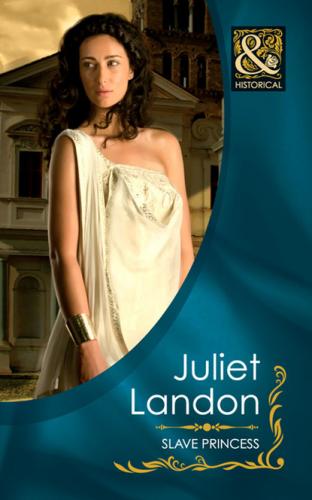

The bench had been pulled up below the window with the curled-up body of a young maid lying motionless at one end, covered with a rich cloak. Trying not to stand on her, her regal mistress of the Briganti tribe balanced on the tips of her toes to see out of the window where the spring sun beamed between scudding clouds, showing her that she was facing home, miles away to the north of Eboracum. The princess, a tall slender woman of twenty-two summers, swayed dangerously as she let go of the bar with one hand to look down at the poor waif. ‘Wait,’ she whispered.

The movement made her dizzy and faint, her legs trembling with the effort of reaching up, her usual robust energy sapped by hunger. Warily, she began her descent, clenching her teeth, commanding her feet to tread where they would do no further damage. In mid-step, she let go of the window-bar as the echoing rattle of a key in the door held her, poised and swaying like a reed, narrowing her eyes in anger at the intrusion. Every time the guard brought food, she was aware of the room’s appalling smell of unwashed bodies, rats, sickness and despair, the very idea of eating almost turning her stomach.

But this time, the armour-plated guard stood back to allow a stranger to enter, a tall white-clad man, obviously an official, who frowned at the sight of the young woman in the belted green tunic with a head of bright copper-coloured hair some way above his, glowing like a halo with the sun behind it. Her lips parted, then closed again quickly. The angry expression remained.

Years of discipline held Quintus’s initial reaction where it would not show, yet his eyes faced the sun and the captive Brigantian caught that first fleeting glimpse of shock before the haughty lids came down like shutters. Clearly, he would have preferred it if she’d been on his level, or even lower, but he took the opportunity her position afforded him to take in the intricately woven green-and-heather plaid, the borders of gold-thread embroidery, the tooled leather shoes and patterned girdle. There was heavy gold on her wrists and neck, a wink of red garnets through the hair, and the cords that wrapped her thick plait were twisted with glass beads from the Norse countries, cornelians and lapis from the other side of the world.

Pretending to ignore her perilous position, Quintus glanced round the room. ‘What’s been happening here?’ he said to the guard, indicating the broken pottery.

‘Her food, sir,’ said the man, expressionless. ‘Everything I bring in gets thrown against the wall. The rats like it well enough.’

‘How long?’

‘Since she set foot in the place, sir. The maid’s ready to pack it in, by the look of things. All she gets is water. Tyrannical, I call it, sir.’

‘Seven … eight days?’

‘Aye, sir. Look ‘ere.’ The guard pointed to his bruised cheek. ‘She threw a bowl at me. They can starve for all I care.’

‘That’s what you get if you don’t wear your helmet,’ Quintus said, dismissively. No wonder the Emperor wants rid of her, he thought. He’d not want her death here in Eboracum. Miles away, perhaps, but not here under his roof. Another glance up at the captive’s face, however, alerted him to the probability of that fate if something was not done immediately to reverse it. She was swaying dangerously, her eyes half-closed in pain.

‘Come down,’ he said, sternly. ‘Take my arm. Come on.’

The guard looked dubious. ‘She’ll not let you touch her, sir.’

But the stern command had reached through a cold haze as if from a long way away, and the hand she put out to steady herself touched something firm and warm that supported her, keeping her from falling. Not for the world would she willingly have allowed any Roman to touch her, nor would she have touched one, but now she found herself being placed carefully upon the floor and helped to sit unsteadily beside her maid’s feet that stuck out from beneath the gold fringe of a cloak. Seated on the edge of the bed, she felt her head being pushed slowly down between her knees in a most undignified manner.

‘Let me up!’ she gasped. ‘I’m all right.’

The guard let out a yelp. ‘Ye gods! That’s the first time she’s said a word, sir. Honest. We all thought she was word-struck!’

‘There’s something to be said for it, in a woman,’ Quintus remarked, removing his hand from her head, ‘but I have a suspicion we shall hear a lot more of it before we’re much older.’ Bending, he picked up the beaker of water from the floor and placed it in the woman’s hand. ‘Take a sip of that,’ he said. ‘Then you’d better listen to me.’

She refused his command, preferring instead to place a hand under her maid’s head and offer the water to her parched lips. With closed eyes sunk deep into brown sockets, the girl could take only a sip before bubbling the rest of it away down her chin, coughing weakly.

‘Are you going to let her die, then?’ said Quintus. ‘Can you not see she has no strength? You may be able to last out a few more weeks, but she won’t. Do you want her death on your hands? No one regards your protest, woman. You’re wasting life for no good reason.’

The captive pulled herself up straight, her back like a ramrod, a token of inflexibility. Her hands