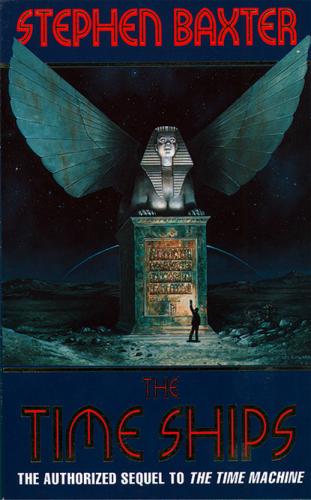

Well, here I was again, a hundred and fifty thousand years before that date. The bushes and lawn were gone – and would never come to be, I suspected. That sunlit garden had been replaced by this bleak, darkened desert, and now existed only in the recesses of my own mind. But the Sphinx was here, solid as life and almost indestructible, it seemed.

I patted the bronze panels of the Sphinx’s pedestal with something resembling affection. Somehow the existence of the Sphinx, lingering from my previous visit, reassured me that I was not imagining all of this, that I was not going mad in some dim recess of my house in 1891! All of this was objectively real, and – no doubt, like the rest of Creation – it all conformed to some logical pattern. The White Sphinx was a part of that pattern, and it was only my ignorance and limitation of mind that prevented me from seeing the rest of it. I was bolstered up, and felt filled with a new determination to continue with my explorations.

On impulse, I walked around to the side of the pedestal closest to the Time Machine, and, by candlelight, I inspected the decorated bronze panel there. It was here, I recalled, that the Morlocks – in that other History – had opened up the hollow base of the Sphinx, and dragged the Time Machine inside the pedestal, meaning to trap me. I had come to the Sphinx with a pebble and hammered at this panel – just here; I ran over the decorations with my fingertips. I had flattened out some of the coils of the panel, though to no avail. Well, now I found those coils firm and round under my fingers, as good as new. It was strange to think that the coils would not meet the fury of my stone for millennia yet – or perhaps, never at all.

I determined to move away from the machine and proceed with my exploration. But the presence of the Sphinx had reminded me of my horror at losing the Time Machine to the clutches of the Morlocks. I patted my pocket – at least without my little levers the machine could not be operated – but there was no obstacle to those loathsome creatures crawling over my machine as soon as I was gone from it, perhaps dismantling it or stealing it again.

And besides, in this darkened landscape, how should I avoid getting lost? How should I be sure of finding the machine again, once I had gone more than a few yards from it?

I puzzled over this for a few moments, my desire to explore further battling with my apprehension. Then an idea struck me. I opened my knapsack and took out my candles and camphor blocks. With rough haste I shoved these articles into crevices in the Time Machine’s complex construction. Then I went around the machine with lighted matches until every one of the blocks and candles was ablaze.

I stood back from my glowing handiwork with some pride. Candle flames glinted from the polished nickel and brass, so that the Time Machine was lit up like some Christmas ornament. In this darkened landscape, and with the machine poised on this denuded hill-side, I would be able to see my beacon from a fair distance. With any luck, the flames would deter any Morlocks – or if they did not, I should see the diminution of the flames immediately and could come running back, to join battle.

I fingered the poker’s heavy handle. I think a part of me hoped for just such an outcome; my hands and lower arms tingled as I remembered the queer, soft sensation of my fists driving into Morlock faces!

At any rate, now I was prepared for my expedition. I picked up my Kodak, lit a small oil lamp, and made my way across the hill, pausing after every few paces to be sure the Time Machine rested undisturbed.

I raised my lamp, but its glow carried only a few feet. All was silent – there was not a breath of wind, not a trickle of water; and I wondered if the Thames still flowed.

For lack of a definite destination, I decided to make towards the site of the great food hall which I remembered from Weena’s day. This lay a little distance to the north-west, further along the hill-side past the White Sphinx, and so this was the path I followed once more – reflecting in Space, if not in Time, my first walk in Weena’s world.

When last I made this little journey, I remembered, there had been grass under my feet – untended and uncropped, but growing neat and short and free of weeds. Now, soft, gritty sand pulled at my boots as I tramped across the hill.

My vision was becoming quite adapted to this night of patchy star-light, but, though there were buildings hereabout, silhouetted against the sky, I saw no sign of my hall. I remembered it quite distinctly: it had been a grey edifice, dilapidated and vast, of fretted stone, with a carved, ornate doorway; and as I had walked through its carved arch, the little Eloi, delicate and pretty, had fluttered about me with their pale limbs and soft robes.

Before long I had walked so far that I knew I must have passed the site of the hall. Evidently – unlike the Sphinx and the Morlocks – the food palace had not survived in this History – or perhaps had never been built, I thought with a shiver; perhaps I had walked – slept, even taken a meal! – in a building without existence.

The path took me to a well, a feature which I remembered from my first jaunt. Just as I recalled, the structure was rimmed with bronze and protected from the weather by a small, oddly delicate cupola. There was some vegetation – jet-black in the star-light – clustered around the cupola. I studied all this with some dread, for these great shafts had been the means by which the Morlocks ascended from their hellish caverns to the sunny world of the Eloi.

The mouth of the well was silent. That struck me as odd, for I remembered hearing from those other wells the thud-thud-thud of the Morlocks’ great engines, deep in their subterranean caverns.

I sat down by the side of the well. The vegetation I had observed appeared to be a kind of lichen; it was soft and dry to the touch, though I did not probe it further, nor attempt to determine its structure. I lifted up the lamp, meaning to hold it over the rim and to see if there might be returned the reflection of water; but the flame flickered, as if in some strong draught, and, in a brief panic at the thought of darkness, I snatched the lamp back.

I ducked my head under the cupola and leaned over the well’s rim, and was greeted by a blast of warm, moist air into the face – it was like opening the door to a Turkish bath – quite unexpected in that hot but arid night of the future. I had an impression of great depth, and at the remote base of the well I fancied my dark-adapted eyes made out a red glow. Despite its appearance, this really was quite unlike the wells of the first Morlocks. There was no sign of the protruding metal hooks in the side, intended to support climbers, and I still detected no evidence of the machinery noises I had heard before; and I had the odd, unverifiable impression that this well was far deeper than those Morlocks’ cavern-drilling.

On a whim, I raised my Kodak and dug out the flash lamp. I filled up the trough of the lamp with blitzlichtpulver, lifted the camera and flooded the well with magnesium light. Its reflections dazzled me, and it was a glow so brilliant that it might not have been seen on earth since the covering of the sun, a hundred thousand years or more earlier. That should have scared away the Morlocks if nothing else! – and I began to concoct protective schemes whereby I could connect the flash to the unattended Time Machine, so that the powder would go off if ever the machine was touched.

I stood up and spent some minutes loading the flash lamp and snapping at random across the hillside around the well. Soon a dense cloud of acrid white smoke from the powder was gathering about me. Perhaps I would be lucky, I reflected, and would capture for the wonderment of Humanity the rump of a fleeing, terrified Morlock!

… There was a scratching, soft and insistent, from a little way around the well rim, not three feet from where I stood.

With a cry, I fumbled at my belt for my poker. Had the Morlocks fallen on me, while I daydreamed?

Poker in hand, I stepped forward with care. The rasping noises were coming from the bed of lichen, I realized; there