‘And what brings you here, sir?’ Hakesby asked.

‘An enquiry, sir. And you?’

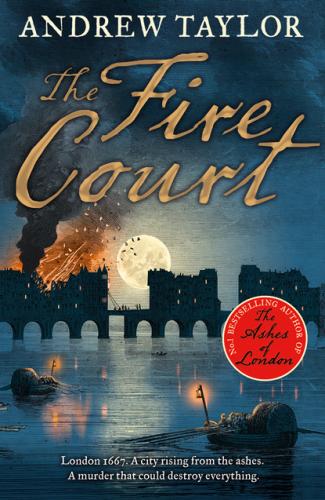

Hakesby nodded towards the hall. ‘The Fire Court has been in session.’

‘Do you often attend?’

‘As occasion requires. When I have clients whose interests are concerned.’

Marwood drew closer. ‘I wonder – indulge me a moment, pray – do the names Twisden, Wyndham or Rainsford mean anything to you?’

‘There’s Sir Wadham Wyndham – he’s a justice of the King’s Bench, and he sits sometimes at the Fire Court. In fact, he was one of the judges sitting there today. Could it be him?’

‘Perhaps. And the others?’

‘I don’t know the names. Could they be connected with the Fire Court as well? You should ask Theophilus Chelling. He’s the Fire Court’s assistant clerk. He will know if anyone does.’

‘I’m not acquainted with him.’

‘I’ll introduce you now, if you wish.’ Hakesby’s eyes moved to his maid and then back to Marwood. ‘I believe there can’t be any harm in it.’

Marwood murmured his thanks, and Hakesby led the way to a doorway in the building that joined the hall range at a right angle. Marwood walked by his side. Jane Hakesby trailed after them, as a servant should.

They climbed stairs of dark wood rising into the gloom of the upper floors. Hakesby’s trembling increased as they climbed, and he was obliged to take Marwood’s arm. The two doors leading to the first-floor apartments were tall and handsome modern additions. On the second floor, the ceilings were lower, the doorways narrower, and the doors themselves were blackened oak as old as the stone that framed them.

Hakesby knocked on the door to the right, and a booming voice commanded them to enter. Mr Chelling rose as they entered. His body and head belonged to a tall man, but nature had seen fit to equip him with very short arms and legs. Grey hair framed a face that was itself on a larger scale than the features that adorned it. The top of his head was on a level with Jane Hakesby’s shoulders.

‘Mr Hakesby – how do you do, sir?’

Hakesby said he was very well, which was palpably untrue, and asked how Chelling did.

Chelling threw up his arms. ‘I wish I could say the same.’

‘Allow me to introduce Mr Marwood.’

‘Your servant, sir.’ Chelling sketched a bow.

‘I am sorry to hear that you’re not well, sir,’ Marwood said.

‘I am well enough in my body.’ Chelling puffed out his chest. ‘It’s the fools I deal with every day that make me unwell. Not the judges, sir, oh no – they are perfect lambs. It’s the authorities at Clifford’s Inn that hamper my work. And then there’s the Court of Aldermen – they will not provide us with the funds we need for the day-to-day administration of the Fire Court, which makes matters so much worse.’

Uninvited, Hakesby sank on to a stool. His maid and Marwood remained standing.

Chelling wagged a plump finger at them. ‘You will be surprised to hear that we have already used ten skins of parchment, sir, for the fair copies of the judgements, together with a ream of finest Amsterdam paper. Scores of quills, too – and sand, naturally, for blotting, and a quart or so of ink. I say nothing of the carpenter’s bill and the tallow-chandler’s, and the cost of charcoal – I assure you, sir, the expense is considerable.’

Hakesby nodded. ‘Indeed, it is quite beyond belief, sir.’

‘It’s not as if we waste money here. All of us recognize the need to be prudent. The judges give their time without charge, for the good of the country. But we must have ready money, sir – you would grant me that, I think? With the best will in the world, the court cannot run itself on air.’

Chelling paused to draw breath. Before he could speak, Hakesby plunged in.

‘Mr Marwood and I had dealings with each other over St Paul’s just after the Fire. I was working with Dr Wren, assessing the damage to the fabric, while my Lord Arlington sent Marwood there to gather information from us.’ When he had a mind to it, Hakesby was almost as unstoppable as Mr Chelling himself. ‘I met him as I was coming out of court just now. He has a question about the judges, and I said I know just the man to ask. So here we are, sir, here we are.’

‘Whitehall, eh?’ Chelling said, turning back to Marwood. ‘Under my Lord Arlington?’

Marwood bowed. ‘Yes, sir. I’m clerk to his under-secretary, Mr Williamson. I’m also the clerk of the Board of Red Cloth, when it meets.’

‘Red Cloth? I don’t think I know it.’

‘It’s in the Groom of the Stool’s department, sir. The King’s Bedchamber.’

Mr Chelling cocked his head, and his manner became markedly more deferential. ‘How interesting, sir. The King’s Bedchamber? A word in the right ear would work wonders for us here. It’s not just money, you see. I meet obstructions at every turn from the governors of this Inn. That’s even worse.’

Marwood bowed again, implying his willingness to help without actually committing himself. There was a hint of the courtier about him now, Jane Hakesby thought, or at least of a man privy to Government secrets. She did not much care for it. He moved his head slightly and the light fell on his face. He no longer looked like a courtier. He looked ill.

She wondered who was dead. Had there been a mother? A father? She could not remember – she had probably never known. For a man who had changed her life, she knew remarkably little about James Marwood. Only that without him she might well be dead or in prison.

‘Mr Marwood has a question for you, sir,’ Hakesby said.

Marwood nodded. ‘It’s a trifling matter. I came across three names – Twisden, Wyndham and Rainsford. I understand there is a Sir Wadham Wyndham, who is one of the Fire Court judges, and—’

‘Ah, sir, the judges.’ Chelling rapped the table beside him for emphasis. ‘Mr Hakesby has brought you to the right man. I know Sir Wadham well. Indeed, I’m acquainted with all the judges. We have a score or so of them. They use the set of chambers below these, the ones on the first floor, which are larger than ours. We have given them a remarkably airy sitting room, though I say it myself who had it prepared for them, and also a retiring room and a closet. Only the other day, the Lord Chief Justice was kind enough to say to me how commodious the chambers were, and how convenient for the Fire Court.’

‘And do the judges include—’

‘Oh yes – Sir Wadham is one, as I said, and so is Sir Thomas Twisden. Sir Thomas has been most assiduous in his attendance. A most distinguished man. I remember—’

‘And Rainsford?’ Marwood put in.

‘Why yes, Sir Richard, but—’

‘Forgive me, sir, one last question. Do any of the other judges have the initials DY?’

Chelling frowned, and considered. ‘I cannot recall. Wait, I have a list here.’ He shuffled the documents on his table and produced a paper which he studied for a moment. ‘No – no one.’ He looked up, and his small, bloodshot eyes stared directly at Marwood. ‘Why do you ask?’

‘I regret, sir, I am not at liberty to say.’

Chelling winked. ‘Say no more, sir. Whitehall business, perhaps, but I ask no questions. Discretion is our watchword.’

Marwood bowed. ‘Thank you for your help, sir. I mustn’t keep you any longer.’

‘You must let me know if there is any other way I can oblige you.’ Chelling tried to smile but his face refused to cooperate fully. ‘And if the opportunity arises,