16 The Strange Case of the Missing Pictures

19 El Día de la Virgen de la Merced

21 Charlie Carver’s Gold Watch

Some Sources and Further Reading

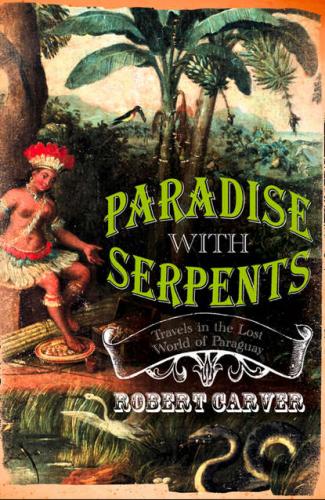

‘When I first came to Asunción from Spain, I realised that I’d arrived in paradise. The air was warm, the light was tropical, and the shuttered colonial houses suggested sensual, tranquil lives. At night we’d go out walking the streets and I’d be aware of two things; the smell of jasmine and the sound of voices in the dark. But like any paradise, this one had serpents.’

Josefina Plá, Spanish poet

In the closing years of the 19th century a forgotten man returned to his home town in the Midlands of England, after an absence of more than thirty years. He had long been given up for dead. His father had been a wealthy man, an industrialist who owned lace factories and coal mines. This man had two sons, one who stayed at home and entered the family businesses, the other who went off to seek his fortune in the United States of America; he was never heard of again, and when the head of the family died his great fortune was left to both of his sons, in equal parts, though one of them had vanished, apparently for ever. In his will he had specified that advertisements in every English-language newspaper around the world should be run, each week, for a year, to inform the lost son of his new fortune, so that he could return to claim it, if he was still alive. At the end of that period, if the missing son had not appeared, his half of the family fortune was to go to charity, to found a theatre and a public hospital. His will was done. No one stepped forward to claim half of the great fortune. As a result, at the end of the year, the Nottingham Playhouse and the Nottingham Free Hospital came into being, founded and funded by half this man’s wealth.

Then, years later, sensationally, a man returned from abroad, claiming to be the missing son. My grandfather Roy, at the time a schoolboy, recalled this event vividly. In his sixties, in the 1950s, Roy told me about this prodigal returned: a tall, massively built man who dressed in ‘the American style’, with broad-brimmed hat, long coat, embroidered high-heeled boots, silver Mexican spurs, and a fancy multicoloured waistcoat. He spoke with a marked American drawl, though spoke little but listened attentively to what others said. This man was Charlie Carver, my great-great-grand-uncle. He had returned home, at last, and he had a very strange tale to tell.

He had left England as a restless young man, determined to seek his fortune in the post-1845 gold and silver diggings of Western America. He had taken ship for San Francisco, and had arrived safely. Several letters had been received by the family back in England. Then nothing – silence for over thirty years. What had happened was as follows: in a bar-room brawl Charlie had been hit over the head, and was knocked unconscious. When he came to he could not remember who he was. He had been robbed and had no papers or possessions to give him any clues as to his identity. He found that he had been shanghai-ed and was on board a sailing clipper bound for Australia, enrolled by persons unknown for a bounty, as a common seaman. For the next five years he served, first as an ordinary seaman, then as ticketed mate, on board the big sailing vessels that crossed the Pacific. For all this time he still had no idea who he was, nor where he came from. He acquired an American accent and mannerisms. Then, tiring of the sea, and taking his savings, he disembarked in the States, determined to seek his fortune on land. He tried many trades and moved from town to town, one of the legion of homeless men drifting around the West in the 1970s and 1980s as the frontier closed in. Finally, he found a good position as a mining supervisor, south of the border, in Mexico. He still had no idea who he was, and was known to many simply as ‘Jack’, or el hombre sin nom – the man with no name. One day, inspecting a shaft deep inside the mine, a distant rumble was heard; it could mean only one thing – a fall. The miners, including Charlie Carver, alias ‘Jack’, all rushed for the distant pinpoint of light that was the entrance. They were too late. Dust, rock, pit props rained down upon them. Amid curses and cries of terror they fell to the ground, crushed under the weight of debris. More than twenty men died in that fall, but Charlie Carver was not one of them. He had a broken wrist and a dislocated shoulder, was bruised and cut about the head, but when the rescue party finally managed to dig the survivors out of the rubble, a shocked, semi-delirious voice cried out, in English, for he could no longer recall any Spanish, ‘I’m Charlie Carver from Nottingham – what am I doing here?’ The blows to his head caused by the rockfall had brought back his knowledge of who he was – and erased his memories of the previous thirty years. He had no idea at all what he had done or where he had been in the missing decades. His last memory was of a fight in a low saloon on the Barbary Coast of San Francisco. This time, however, there were clues – his bankbook, his mate’s ticket and discharge papers, his clothes with their tell-tale maker’s labels from San Francisco and Sydney. And there were people at the mine who had known where he had been, where he had worked before, because he had told them before the accident.

After he recovered his health he became a detective on the trail of his own past. He retraced his steps, back to San Francisco. There, in the shipping offices and newspaper stacks where the back-numbers were kept, he was able to trace his life as an anonymous seaman from the arrivals and departures of the grain ships, the muster lists and crew signings-on; on his mate’s ticket he was described simply as ‘Jack of England, Full Mate and Master-Mariner’. He had made his mark on the ticket, not signed it, indicating that in that other life he could not write. Somewhere in his travels he had learnt to use a knife and revolver. He found a keenly whetted blade in a leather sheath hidden in his left boot, and a pair of old, battered, but very serviceable Navy Colt .45 revolvers wrapped in oilskins. On his own body he found scars which he had a doctor examine: they were from the cat-o’-nine-tails, from fist fights, from knife wounds, and at least two puckered scars were old bullet wounds. On his back the doctor also discovered a tattoo of a Polynesian type then only found in Tahiti, made with native ink. It was in the newspaper offices in San Francisco that he saw the advertisements placed for him all those years ago, after his father died. He said afterwards, when he returned to England, that this was the only moment he lost himself, when, alone and surrounded by mounds of yellowing newsprint, he broke down and wept uncontrollably. He said he could still remember the bay rum lotion his father had used after shaving, the memory of it driving him to despair in his loss and pain.

He was now two men. In his mind he was still the young, foolhardy, naive