[Conceit and humbug! End of extract – G. de R.]

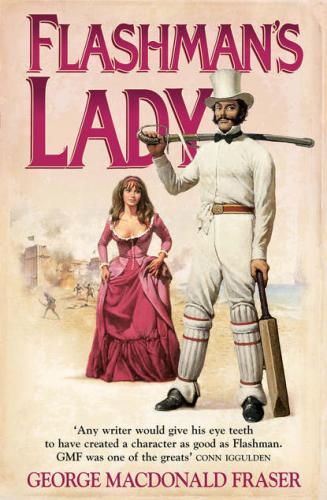

There’s no doubt that a good gallop before work is the best training you can have, for that afternoon I bowled the best long spell of my life for Mynn’s Casuals against the All-England XI: five wickets for 12 in eleven overs, with Lillywhite leg before and Marsden clean bowled amongst them. I’d never have done that on cold baths and dumbbells, so you can see that what our present Test match fellows need is some sporting female like Mrs Leo Lade to look after ’em, then we’d have the Australians begging for mercy.

The only small cloud on my horizon, as we took tea afterwards in the marquee among the fashionable throng, with Elspeth clinging to my arm and Mynn passing round bubbly in the challenge cup we’d won, was whether Solomon had recognised me in the drawing-room that morning, and if so, would he keep his mouth shut? I wasn’t over concerned, for all he’d had in view was my stalwart back and buttocks heaving away and Mrs Lade’s stupefied face reflected in the mirror – it didn’t matter a three-ha’penny what he said about her, and even if he’d recognized me as t’other coupler, it wasn’t likely that he’d bruit it about; chaps didn’t, in those days. And there wasn’t even a hint of a knowing twinkle in his eye as he came over to congratulate me, all cheery smiles, refilling my glass and exclaiming to Elspeth that her husband was the most tearaway bowler in the country, and ought to be in the All-England side himself, blessed if he shouldn’t. A few of those present cried, ‘Hear, hear,’ and Solomon wagged his head admiringly – the artful, conniving scoundrel.

‘D’ye know,’ says he, addressing those nearest, who included many of his house party, as well as Mynn and Felix and Ponsonby-Fane, ‘I shouldn’t wonder if Harry wasn’t the fastest man in England just now – I don’t say the best, in deference to distinguished company’ – and he bowed gracefully towards Mynn – ‘but certainly the quickest; what d’you think, Mr Felix?’

Felix blinked and blushed, as he always did at being singled out, and said he wasn’t sure; when he was at the crease, he added gravely, he didn’t consider miles per hour, but any batter who faced Mynn at one end and me at t’other would have something to tell his grandchildren about. Everyone laughed, and Solomon cries, lucky men indeed; wouldn’t tyro cricketers like himself just jump at the chance of facing a few overs from us. Not that they’d last long, to be sure, but the honour would be worth it.

‘I don’t suppose,’ he added, fingering his earring and looking impish at me, ‘you’d consider playing me a single-wicket match, would you?’

Being cheerful with bubbly and my five for 12, I laughed and said I’d be glad to oblige, but he’d better get himself cover from Lloyd’s, or a suit of armour. ‘Why,’ says I, ‘d’you fancy your chance?’ and he shrugged and said no, not exactly; he knew he mightn’t make much of a show, but he was game to try. ‘After all,’ says he, tongue in cheek, ‘you ain’t Fuller Pilch as a batter, you know.’

There are moments, and they have a habit of sticking in memory, when light-hearted, easy fun suddenly becomes dead serious. I can picture that moment now; the marquee with its throng of men in their whites, the ladies in their bright summer confections, the stuffy smell of grass and canvas, the sound of the tent-flap stirring in the warm breeze, the tinkle of plates and glasses, the chatter and the polite laughter, Elspth smiling eagerly over her strawberries and cream, Mynn’s big red face glistening, and Solomon opposite me – huge and smiling in his bottle-green coat, the emerald pin in his scarf, the brown varnished face with its smiling dark eyes, the carefully dressed black curls and whiskers, the big, delicately manicured hand spinning his glass by the stem.

‘Just for fun,’ says he. ‘Give me something to boast about, anyway – play on my lawn at the house. Come on’ – and he poked me in the ribs – ‘I dare you, Harry,’ at which they chortled and said he was a game bird, all right.

I didn’t know, then, that it mattered, although something warned me that there was a hint of humbug about it, but with the champagne working and Elspeth miaowing eagerly I couldn’t see any harm.

‘Very good,’ says I, ‘they’re your ribs, you know. How many a side?’

‘Oh, just the two of us,’ says he. ‘No fieldsmen; bounds, of course, but no byes or overthrows. I’m not built for chasing,’ and he patted his guts, smiling. ‘Couple of hands, what? Double my chance of winning a run or two.’

‘What about stakes?’ laughs Mynn. ‘Can’t have a match like this for just a tizzy,’fn1 winking at me.

‘What you will,’ says Solomon easily. ‘All one to me – fiver, pony, monkey, thou. – don’t matter, since I shan’t be winning it anyway.’

Now that’s the kind of talk that sends any sensible man diving for his hat and the nearest doorway, usually; otherwise you find yourself an hour later scribbling IOUs and trying to think of a false name. But this was different – after all, I was first-class, and he wasn’t even thought about; no one had seen him play, even. He couldn’t hope for anything against my expresses – and one thing was sure, he didn’t need my money.

‘Hold on, though,’ says I. ‘We ain’t all nabob millionaires, you know. Lieutenant’s half-pay don’t stretch—’

Elspeth absolutely reached for her reticule, d--n her, whispering that I must afford whatever Don Solomon put up, and while I was trying to hush her, Solomon says:

‘Not a bit of it – I’ll wager the thou., on my side; it’s my proposal, after all, so I must be ready to stand the racket. Harry can put up what he pleases – what d’ye say, old boy?’

Well, everyone knew he was filthy rich and careless with it, so if he wanted to lose a thousand for the privilege of having me trim him up, I didn’t mind. I couldn’t think what to offer as a wager against his money, though, and said so.

‘Well, make it a pint of ale,’ says he, and then snapped his fingers. ‘Tell you what – I’ll name what your stake’s to be, and I promise you, if you lose and have to stump up, it’s something that won’t cost you a penny.’

‘What’s that?’ says I, all leery in a moment.

‘Are you game?’ cries he.

‘Tell us my stake first,’ says I.

‘Well, you can’t cry off now, anyway,’ says he, beaming triumphantly. ‘It’s this: a thou. on my side, if you win, and if I win – which you’ll admit ain’t likely’ – he paused, to keep everyone in suspense – ‘if I win, you’ll allow Elspeth and her father to come on my voyage.’ He beamed round at the company. ‘What’s fairer than that, I should like to know?’

The bare-faced sauce of it took my breath away. Here was this fat upstart, with his nigger airs, who had proclaimed his interest in my wife and proposed publicly to take her jaunting while I was left cuckolded at home, had been properly and politely warned off, and was now back on the same tack, but trying to pass it off as a jolly, light-hearted game. My skin burned with fury – had he cooked this up with Elspeth? – but one glance told me she was as astonished as I was. Others were smiling, though, and I saw two ladies whispering behind their parasols; Mrs Lade was watching with amusement.

‘Well, well, Don,’ says I, deliberately easy. ‘You don’t give up in a hurry, do you?’

‘Oh, come, Harry,’ cries he. ‘What hope have I? It’s just nonsense, for you’re sure to win. Doesn’t he always win, Mrs Lade?’ And he looked at her, smiling, and then at me, and at Elspeth, without a flicker of expression – by G-d, had he recognised my heaving stern in the drawing-room, after all, and was he daring