‘I suppose I’ve grown used to supporting myself.’

‘And a wife supported her husband in other ways. Made a home for him.’ Unexpectedly, she laughed, a bubbling hiss from the back of her throat. ‘And in the case of a vicar’s wife, she usually ran the parish as well. You’ll have plenty to do here without going out to work.’

‘It’s up to Vanessa, of course,’ I said. ‘By the way, how are you feeling?’

‘Awful. That damned doctor keeps giving me new medicines, but all they do is bung me up and give me bad dreams.’ She waved a brown, twisted hand at the box on the stool. ‘I dreamt about that last night. I dreamt I found a dead bird inside. A goose. Told the girl I wanted it roasted for lunch. Then I saw it was crawling with maggots.’ There was another laugh. ‘That’ll teach me to go rummaging through the past.’

‘Is that what you’ve been doing?’ Vanessa asked. ‘In there?’

‘I have to do something. I never realized you can be tired and in pain and bored – all at the same time. The girl told me that the Oliphant woman had written a history of Roth. So I made her buy me a copy. Not as bad as I thought it was going to be.’ She glared at me. ‘I suppose you had a hand in it.’

‘Vanessa and I edited it, yes, and Vanessa saw it through the press.’

‘Thought so. Anyway, it made me curious. I knew there was a lot of rubbish up in the attic. Papers, and so on. George had them put up there when we moved from the other house. Said he was going to write the family history. God knows why. Literature wasn’t his line at all. Didn’t know one end of a pen from another. Anyway, he never had the opportunity. So all the rubbish just stayed up there.’

Vanessa leant forwards. ‘Do you think you might write something yourself?’

Lady Youlgreave held up her right hand. ‘With fingers like this?’ She let the hand drop on her lap. ‘Besides, what does it matter? It’s all over with. They’re all dead and buried. Who cares what they did or why they did it?’

She stared out of the window at the bird table. I wondered if the morphine were affecting her mind. James Vintner had told me that he had increased the dose recently. Like the house and the dogs, their owner was sliding into decay.

I said, ‘Vanessa’s read quite a lot of Francis Youlgreave’s verse.’

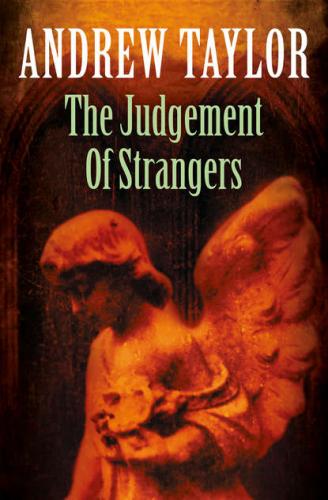

‘I’ve got a copy of The Four Last Things,’ Vanessa said. ‘The one with “The Judgement of Strangers” in it.’

Lady Youlgreave stared at her for a moment. ‘There were two other collections, The Tongues of Angels and Last Poems. He published Last Poems when he was still up at Oxford. Silly man. So pretentious.’ Her eyes moved to me. ‘Pass me that book,’ she demanded. ‘The black one on the corner of the table.’

I handed her a quarto-sized hardback notebook. The seconds ticked by while she opened it and tried to find the page she wanted. Vanessa and I looked at each other. Inside the notebook I saw yellowing paper, unlined and flecked with damp, covered with erratic lines of handwriting in brown ink.

‘There,’ Lady Youlgreave said at last, placing the open notebook on her side table and turning it so it was the right way up for Vanessa and me. ‘Read that.’

The handwriting was a mass of blots and corrections. Two lines leapt out at me, however, because they were the only ones which had no alterations or blemishes:

Then darkness descended; and whispers defiled

The judgement of stranger, and widow, and child.

‘Is that his writing?’ Vanessa asked, her voice strained.

Lady Youlgreave nodded. ‘This is a volume of his journal. March eighteen-ninety-four, while he was still in London.’ The lips twisted. ‘He was the vicar of St Michael’s in Beauclerk Place. I think this was the first draft.’ She looked up at us, at our eager faces, then slowly closed the book. ‘According to this journal, it was a command performance.’

Vanessa raised her eyebrows. ‘I don’t understand.’

Lady Youlgreave drew the book towards her and clasped it on her lap. ‘He wrote the first half of the first draft in a frenzy of inspiration in the early hours of the morning. He had just had an angelic visitation. He believed that the angel had told him to write the poem.’ Once more her lips curled and she looked from me to Vanessa. ‘He was intoxicated at the time, of course. He had been smoking opium earlier that evening. He used to patronize an establishment in Leicester Square.’ Her head swayed on her neck. ‘An establishment which seems to have catered for a variety of tastes.’

‘Are there many of his journals?’ asked Vanessa. ‘Or manuscripts of his poems? Or letters?’

‘Quite a few. I’ve not had time to go through everything yet.’

‘As you know, I’m a publisher. I can’t help wondering if you might have the material for a biography of Francis Youlgreave there.’

‘Very likely. For example, his journal gives a very different view of the Rosington scandal. From the horse’s mouth, as it were.’ Her lips twisted and she made a hissing sound. ‘The trouble is, this particular horse isn’t always a reliable witness. George’s father used to say – but I mustn’t keep you waiting like this. You haven’t had any sherry yet. I’m sure we’ve got some somewhere.’

‘It doesn’t matter,’ I said.

‘The girl will know. She’s late. She should be bringing me my lunch.’

The heavy eyelids, like dough-coloured rubber, drooped over the eyes. The fingers twitched, but did not relax their hold of Francis Youlgreave’s journal.

‘I think perhaps we’d better be going,’ I said. ‘Leave you to your lunch.’

‘You can give me my medicine first.’ The eyes were fully open again and suddenly alert. ‘It’s the bottle on the mantelpiece.’

I hesitated. ‘Are you sure it’s the right time?’

‘I always have it before lunch,’ she snapped. ‘That’s what Dr Vintner said. It’s before lunch, isn’t it? And the girl’s late. She’s supposed to be bringing me my lunch.’

There was a clean glass and a spoon beside the bottle on the mantelpiece. I measured out a dose and gave her the glass. She clasped it in both hands and drank it at once. She sat back, still cradling the glass. A dribble of liquid ran down her chin.

‘I’ll leave a note,’ I said. ‘Just to say that you’ve had your medicine.’

‘But there’s no need to write a note. I’ll tell Doris myself.’

‘It won’t be Doris,’ I said. ‘It’s the weekend, so it’s the nurse who’ll come in.’

‘Silly woman. Thinks I’m deaf. Thinks I’m senile. Anyway, I told you: I’ll tell her myself.’

I could be obstinate, too. I scribbled a few words in pencil on a page torn from my diary and left it under the bottle for the nurse. Lady Youlgreave barely acknowledged us when we said goodbye. But when we were almost at the door, she stirred.

‘Come and see me again soon,’ she commanded. ‘Both of you. Perhaps you’d like to look at some of Uncle Francis’s things. He was very interested in sex, you know.’ She made a hissing noise again, her way of expressing mirth. ‘Just like you, David.’

Vanessa and I were married on a rainy Saturday in April. Henry Appleyard was my best man. Michael gave us a present, a battered but beautiful seventeenth-century French edition of Ecclesiasticus; according to the bookplate it had once been part of the library of Rosington Theological College.

‘It