The president’s own unpredictable personality also weakened the movement he headed. His decision to become a Catholic in 1932 alienated many in Plaid’s naturally Nonconformist constituency. Yet it was a typically bold Lewis gesture that won Plaid international attention in 1936 and put Alun Pugh’s devotion to the cause to the test. Lewis’s firebomb attack on an RAF training base near Pwllheli on the Lleyn peninsula caused outrage. The ‘bombing school’, as Lewis dubbed it, represented for him British military imperialism in Wales.

For Alun Pugh this was a crucial moment. As a member of the Bar, he could not but deplore breaking the law. Yet as historian Dafydd Glyn Jones has argued, the fire was ‘the first time in five centuries that Wales had struck back at England with a measure of violence … to the Welsh people, who had long ceased to believe that they had it in them, it was a profound shock.’ Such an awakening was what Alun Pugh had been yearning for.

Already before the ‘bombing-school’ episode, the strain between the different elements in Alun Pugh’s life had emerged in his letters to J. E. Jones, a London-based teacher and Plaid’s secretary. ‘The time has come,’ he acknowledged in March 1933, ‘for us to have secret societies to work for Wales – two sorts of societies – one of rich supporters to give advice to us without coming into the open, and the other of more adventurous people willing to destroy English advertisements that are put up by local authorities.’ For all his bravado and implied association with the second group, Alun Pugh’s role was largely confined to the first, as a later letter to Jones in June 1934 testifies when he offers to make a loan to the party.

In the following month he sent some legal advice to Jones but insisted that, if it were used, ‘don’t put my name to it’. In March 1936 he was urging Jones or ‘someone else’ to write a letter to The Times on ‘some other burning issue’, but was obviously unwilling to do so himself. The possibility of compromising his position at the Bar was already exercising his mind. Yet in the same month he told Jones that he was lobbying Lloyd George, through a contact of Kathleen Pugh’s, to give public support to Lewis, who had already embarked on his fire-bombing campaign.

In responding to Lewis’s arrest and trial after the attack on the bombing school, Alun Pugh took a big risk. He gave the defendant legal advice-the case against him and two co-conspirators was transferred from a Welsh court, where the jury could not reach a decision, to the Old Bailey, where the three were sentenced to nine months. ‘Thank you very much,’ wrote J. E. Jones to Alun Pugh in September 1936, ‘for your work in defending the three that burnt the bombing school.’ Alun Pugh clung to the fact that Lewis was advocating violence against public installations, not individuals or private property, but it was a difficult circle to square, his heart ruling his head and potentially posing a threat to his career. His solution was, it seemed, to put different parts of his life into boxes – Wales, the law and, separate from both, his family.

‘As a small child,’ recalls his daughter Ann, ‘I used to be terrified that we would have a knock on the door at three o’clock in the morning and it would be the police coming for my father because he was part of it. There was an attack on a reservoir in the north that supplied Liverpool. The Welsh nationalists were indignant that Welsh water was being piped to England.’

Alun Pugh’s relationship with Lewis underwent further strains with the coming of the Second World War. Lewis’s insistence that it was an English war and nothing to do with the Welsh offended Alun Pugh’s sense of patriotism and ran counter to his own determination to contribute as fully as his injury allowed to the war effort. The detachment of Alun Pugh from active involvement in the Welsh cause gathered pace in the post-war years: his appointment as a judge reduced his freedom for manoeuvre and also crucially provided him with an alternative source for self-definition to his Welsh roots. Yet a link endured through Lewis’s two decades in the wilderness following his defeat by a Welsh-speaking Liberal in a by-election for the only Welsh university seat in 1943, subsequent splits in Plaid about tactics, and on to the great nationalist and Welsh language surge of the 1960s.

However, in the early days there was a strong contrast between Alun Pugh’s middle-class enthusiasm in London and the custom, in many primary schools in the valleys in the 1920s and 1930s, of placing the ‘Welsh knot’ – a rope equivalent of the dunce’s hat – over the head of any child caught speaking Welsh. Practical as many of Alun Pugh’s concerns were for Wales, they were tinged with idealism. He could afford his principles and time off to attend Plaid’s most successful innovation of the period – summer schools. Others, at a time of record unemployment, could not.

The reality of events on the ground is demonstrated by the fate of Ty Newydd (New Cottage), the house in Llanon where Alun Pugh’s mother had grown up with her aunt and uncle. It was bequeathed to him some time after the First World War and later he in turn gave it to Plaid Cymru on condition that it was used only by Welsh-speakers to further the cause. Within a short period of time it was being used, according to Ann, by ‘all and sundry’. The fact that he gave a valuable property to the cause – and not to his family – is evidence, she feels, of the extent to which he could separate his obligations to one or the other in his head and discard the conventional route of leaving such an asset to his children. Yet there were deep ambiguities in Alun Pugh’s attitude: he insisted that a plaque commemorating his son David, who had by that time died, had to be erected in the house before it could be handed over to Plaid.

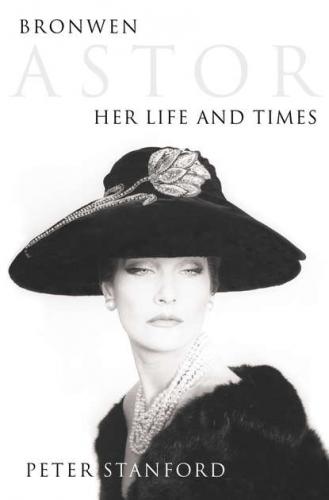

If he placed each of his responsibilities into separate categories, Alun Pugh never failed to convey the importance of their Welsh roots to his children. ‘We were always very conscious that we were different from most people,’ Bronwen recalls. ‘Primarily it was because we were Welsh, but other things led from that. We were taught to be classless, apart from the class system, and our parents encouraged us to look at things differently. The general atmosphere in our family was not rebellion but revolution. It’s a subtle difference. Outwardly you conform, but all the time you are doing things and thinking things in a different way from others.’ When later she found herself in the class-ridden world of Cliveden, this alternative side of her upbringing gave her the resilience to withstand those who would judge her on the basis of her parents’ income and social standing.

At home Alun Pugh’s conversation over breakfast every morning was always in Welsh. The children became adept at remembering the right word for bread or butter or milk. Sunday worship would often be in the Welsh chapel, though later the Pugh became more solidly and conventionally Church of England. And when it came to schooling, Alun Pugh decided – despite his wife’s reluctance – to send their daughters to boarding school in Wales.

The Pugh children fell into two distinct duos, based on age and emphasised by their names, one pair solidly English, the other ringingly Welsh. David and Ann, thirteen and ten respectively when Bronwen was born, formed one unit, while their new sister and five-year-old Gwyneth were another. In 1926, with the help of Kathleen’s parents, the Pughs had purchased an empty plot of land in Pilgrims Lane two streets away in Hampstead and built a larger house. Number 12 still stands to this day, a suburban version of a gabled country house in Sussex vernacular style, with leaded windows and a formal garden sweeping round the house and down the hill towards the Heath.

Alun and Kathleen Pugh had intended to have no more than three children. Bronwen was not planned. Her parents decided the baby was going to be a boy. They even chose a name – Roderick. Two girls, two boys would have made for a neat symmetry, but there was a more particular reason. David, already away at boarding school, was proving a sickly child, undistinguished in his academic work, poor in exams, unable to participate in sport, underdeveloped physically, mentally and emotionally. At the age of sixteen, Bronwen recalls, he was still insisting that a place be set at the dining table for his imaginary friend, Fern. The contrast with Ann, three years his junior and a robust, practical, natural achiever, could not have been greater. Even if it had not been their original intention, circumstances meant that the Pughs, unusually for the time, made no distinction between their treatment of their son and