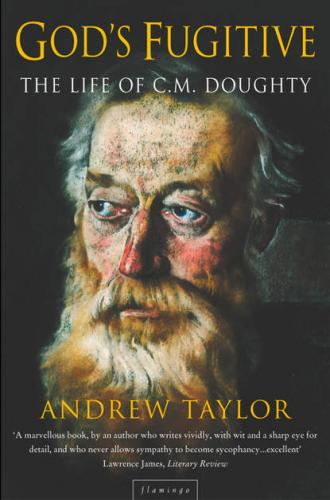

GOD’S FUGITIVE

The Life of Charles Montagu Doughty

Andrew Taylor

Looking in one direction,

this book is dedicated to

HARRY TAYLOR

and in the other

to

SAM, ABIGAIL AND REBECCA

The traveller must be himself in men’s eyes, a man worthy to live under the bent of God’s heaven, and were it without a religion; he is such who has a clean human heart and longsuffering under his bare shirt: it is enough, and though the way be full of harms, he may travel to the ends of the world.

Travels in Arabia Deserta, i, p. 56

CONTENTS

Charles Montagu Doughty was the foremost Arabian explorer of his or any other age. His two years of wandering with the bedu through the oasis towns and deserts started a tradition of British exploration and discovery by travellers who acknowledged him as their master, and he returned to England to write one of the greatest and most original travel books.

He was that unlikely adventurer for his day, a man who would not kill – and yet he had strength and passion, and could face the threat of his own death without flinching. As a writer, he believed in his writing and in his vision when nobody else did; turning his back on exploration, he dedicated his life to poetry and struggled singlehandedly to change the direction of English literature. He lived through the greatest revolution in thought the world had ever seen, and spent a lifetime wrestling with his conscience over its consequences.

Among his admirers as an artist were George Bernard Shaw, who found Arabia Deserta inexhaustible. ‘You can open it and dip into it anywhere all the rest of your life,’ he declared.1 There were F. R. Leavis, Edwin Muir, Wyndham Lewis and, most ardent of all, T. E. Lawrence. Seven Pillars of Wisdom is, in its way, Lawrence’s own homage to Doughty.

And now he is virtually forgotten, his dense and idiosyncratic works valued by antiquarian booksellers and lovers of Arabia, but practically unknown to the readers of a simpler, less painstaking age. The achievement of his travels on foot and by camel seems overshadowed in the days of four-wheel-drive vehicles, helicopters, satellite navigation systems, supply-drops and commercial sponsorship. The great desert journeys are now all in the past. The tradition of Arabian exploration can never be recovered: it is as much a part of history today as the crossing of the Atlantic, or the search for the source of the Nile.

It was Wilfred Thesiger, another great Arabian explorer, who observed that there could never again be a camel-crossing of the desert like his own in the 1940s, or those of the explorers who went before him. ‘I was the last of the Arabian explorers, because afterwards, there were the cars,’ he said. ‘When I made my journeys in Arabia, there was no possibility of travelling in any other way than the way I went. If you could go in a car, it would turn the whole journey into a stunt.’2

Thesiger was the last of a line that included Harry St John Philby, father of the Russian spy and the dedicated servant of Ibn Saud, King of Arabia; there was Bertram Thomas, the civil servant who saved up his holidays for his desert expeditions, and became the first European to cross the Empty Quarter; and Gertrude Bell, who travelled to Arabia in the shadow of a disastrous love affair,3 and demanded that the rulers of Hail treat her like the lady she was and cash her a cheque for £200.

There were the Blunts, Wilfrid and Lady Anne,