On Christmas Eve –

Rosellen ladles mulled wine into the punch glass she picked up for a quarter at the Denman Mall thrift shop. It once belonged to a set: bowl, dipper, goblets. She lifts the orphan to her lips, avoids the chip in the rim.

“To you. To us. To the Santa Maria, too. Bless this ship and all who sailed on her.”

She can tell by her visitor’s impatient radiance, by the thickening perfume and the unaccustomed current in the room, that J.C. would rather forego the speeches. If he had a foot, he’d stamp it. He wants what he’s come for. He wants their game. He wants Hunt the Angel.

“Hold your horses, Mr. Pushy-Pants.”

She takes a long, slow sip.

“I waited long enough for you.”

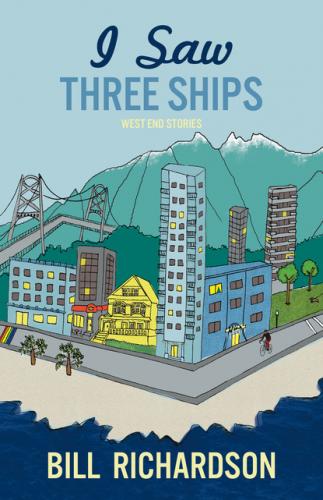

This strained foreplay precedes the wide-ranging probe that will be their main business. They’ll start, as traditions dictates, in 101, not that Rosellen has any thought of finding it there. It’s 422 square feet, with no surfeit of angel-sized hidey-holes. Also, she’s been “decrapifying.” Everyone in the building – those few who still remain – has been similarly engaged. The Santa Maria’s end is nigh, ditto the Nina and the Pinta on either side: three-storey walk-ups, stucco-clad, ordinary structures that for sixty years have given ordinary shelter to ordinary people leading lives that are as ordinary as any life is allowed to be.

It’s not as though they haven’t all seen it coming. They’ve been waiting on death row for the last eighteen months, ever since a developer scooped them up, all three, as though in a game of jacks. The Nina, the Pinta, the Santa Maria, taking up all that space, three minutes from the park, three minutes from the beach, three sisters past their prime, arm in arm in arm, waiting for the streetcar named Expire.

Now, passersby study the promissory eyesore of a billboard besmirching the little lawn outside the building. It depicts a fanciful rendering of a brave new world, populated by happy, young, hand-holding couples – all combinations/permutations of genders and races – walking cheek-by-jowl with smiling oldsters who are similarly diverse in their depictions, on whom has been conferred a range of physical abilities, some supporting themselves on walkers, some on scooters, some jogging with unseemly avidity, while all around are rainbow-coloured children clutching balloons or holding leashes attached to well-mannered puppies with Frisbees in the clench of their drool-free jaws: these are the blessed, the well-contented, the eventual inhabitants of the 150 units – some market rate, some subsidized – that will comprise “Three Ships,” as the new edifice is to be called. Occupancy by late fall 2020. Move in in time for the holidays. Come home to Three Ships, your Utopia-by-the-Bay.

On Christmas Eve –

“In here?” asks Rosellen, teasingly; J.C. is beginning to jostle.

She opens a closet, opens the small wooden box where she keeps paper clips, eraser nubs, opens a cutlery drawer, the freezer compartment of her fridge; a fridge so old it needs weekly defrosting. Rosellen thinks she won’t miss the fridge. She will miss the fridge.

“Or here, or here, or here? Where can it be?”

J.C. tolerates this foolishness, barely. Once, a wine glass fell, seemingly of its own accord; toppled from the counter for no good reason, shattered on the hard tile floor. A month later she was still finding tiny shards. Rosellen took note. This was how it was. Unpredictable when riled. Men were, in her experience. Well. She understands his reluctance to linger. 101 was where he cut the tie. That much Rosellen knows about J.C., knows for sure.

Brigitte Hensel found him. Brigitte lived in 102. She thought to look in because it had snowed and the walk hadn’t been cleared. That was unlike J.C., always quick off the mark with a shovel and a broom and salt. Brigitte knocked. No reply. She yoo-hooed. Silence from the other side. Her third eye opened. A sixth sense warmed. She happened to have a key for the apartment, a spare given her by J.C.’s predecessor, Keith, a nice enough man, but careless, prone to locking himself out. Brigitte kept the key in a safe place, in the left shoe of a pair she no longer wore – they were stylish but bothered her bunions.

Brigitte shared all this with Rosellen her first day on the job, sought her out within hours of her arrival, recounted how she’d held her breath, had steadied herself, had feared the worst. She turned the key. Brigitte told Rosellen – who put the kettle on, for it was clear this would not be a brief visit – what she saw when she stood in the doorway, saw too vividly even though the blinds were drawn, the room was dim, told her about the silence, eerie and dense, about a suffusing clamminess she wasn’t just imagining, told her how she debated whether to call the police or an ambulance, then summoned both, the fire department came too, there were emergency service vehicles lined up all down the block, told her all about what J.C. had done, told her in more procedural detail, with more causal and casual speculation than Rosellen thought necessary.

Brigitte had lived in the Santa Maria since 1954. She was the last of the original tenants, had outlasted Sandra Healey by a full ten years. Sandra was a loner, moody, no friends in the building, no friends anywhere, really, no family in the city, a niece somewhere in the interior, Revelstoke perhaps, maybe Trail, also a sister in Edmonton from whom she was known to be estranged. It wasn’t unusual for weeks to go by without a Sandra sighting. She bought in bulk, didn’t subscribe to any magazines or newspapers, never seemed to receive any mail, so of course no one thought anything of it, why would they? Brigitte didn’t have a key to Sandra’s apartment. No one had a key to Sandra’s apartment. An axe was deployed to enter Sandra’s apartment.

“Can you guess how we knew she was gone?”

“I’m sorry I don’t have any biscuits,” said Rosellen.

“J.C. always had Digestives.”

Brigitte, the Santa Maria’s living memory and conscience, was anxious to impress upon Rosellen that she, the new janitor – Rosellen, a certified property manager, bristled silently – cleave to the high bar established by her predecessors in the custodial arts, of whom there had been but two, both men. At stake was the honour of not just the building but also her sex. Brigitte made it known, with force, that the Nina, and the Pinta, and the Santa Maria were famous in the neighbourhood for the quality and quantity of their seasonal decorations. The Nina laid claim to Halloween, the Pinta to Valentine’s Day. It fell to the Santa Maria to go all out at Christmas. There had never been a time when this order of high holy day precedence was not observed. Never. For a few years, a fellow named O’Rourke had tried, for obvious reasons, to whip up some froth around St. Patrick’s Day, but it never took. He grew bitter. He moved. Good riddance.

There was one storage unit, Brigitte explained, the largest of them, in which building supplies were located: cleaning equipment, fire-exit replacement bulbs, the Suite for Rent sign, etc. Also, there were several packing crates containing everything ornamental required to make the season bright. Rosellen would find grade-A plastic greenery, holly and cedar boughs and frosted pine cones, also foil garlands that blared out festive wishes: “GOOD WILL TO MEN!” “PEACE ON EARTH.!” There was an inflatable St. Nicholas that glowed with an inner light. There was a darling crèche cobbled together entirely out of sponges and pipe cleaners, handcrafted by Mr. Parker, who had lived in 301, who perished from snake bite while visiting the Grand Canyon. Travel was fraught; Brigitte herself preferred to be at home. There