“Thanks,” Arnold said again. He touched the leaves and they crossed over themselves primly, like a woman crossing her legs under her skirt.

“You’re welcome,” Gloria said. “Oh, and please tell your big sister to come in and introduce herself. Alison’s her name, right?”

CHAPTER 2

While Arnold sneaked out the emergency exit in hopes of avoiding the bullies who had chased him into the library earlier in the day, Alison had to run her own gauntlet walking home from school. She didn’t have to worry about the likes of Matt Walters or Jared Nichols lying in wait—they were the ones who should be worrying about her, if they laid a hand on her kid brother again—but she did have to worry about running into Barry Freed. The balding old hippie was tall and stringy and smelly, and somehow he was always in her path even if she took the long way home, around the trailer park.

Home was already in sight when he stepped out suddenly from the alley between the Value-Mart and the Church of Christ. Alison stifled a scream. It wouldn’t do to let Barry know she was afraid of him, especially if the rumors were true and he really was an old pervert.

“It’s all a lie, you know,” he said, his wandering, cloudy right eye seeming to linger where it shouldn’t, on her chest, before rolling up to the blank gray sky.

I’m annoyed, not afraid, Alison told herself, and tried to make her voice show it. “Can we talk about this some other time? I have to get home, Mr. Freed.”

His good eye focused on her face and began to tear up. “That’s what they want. For you to go home and do your homework like a good little girl, be an obedient cog in their machine.”

Alison had inherited her father’s sharp tongue. “A cog can’t be obedient, Mr. Freed. It’s just a piece of metal.”

“And you might as well be just a piece of metal, if you do what they want all the time.”‘

“Who are they, Mr. Freed?”

Alison regretted asking the question immediately, but it was too late. The old hippie leaned in and breathed sour breath in her face. The stink his clothes gave off showed why all the kids in town called him Barry Peed. “They, them. The President, the FBI, the CIA. J. Edgar Hoover—”

“Is dead, Mr. Freed. A long time ago.”

“That’s what they want you to think.” There was no point arguing with him. Not when he still called the High Satrap “the president,” which hadn’t been his official title in, like, forty years. Dad said that poor Mr. Freed was delusional, which meant there was no talking him out of the crazy stuff he believed in. On the other hand, plenty of people believed crazy stuff, and nobody thought any worse of them as long as they didn’t go to the bathroom in their clothes.

He tilted his head back, and Alison clapped her hands over her ears a moment too late—he had already started his infamous imitation of the most famous moment in history. “That’s one small step for a man, one giant step for—what in God’s name is that?” Alison unblocked her ears and tried to edge around Mr. Freed, who was talking in his normal cracked voice. “I mean, does that even sound plausible to you? The government goes to all that trouble and expense to put a man on the moon, and the High Ones choose that very moment to show up and announce their presence to the world?”

“You’re spitting, Mr. Freed. And you’re not making any sense.” Not that that ever stopped him. “They’ve explained a million times how that was the best way they could be sure of reaching everyone at the same time, since, like, a billion people were watching the moon landing on TV, and what better way to show everyone they were friendly than picking up all three Apollo astronauts and putting them down on the South Lawn of the White House an hour later—”

“Ha!” They were starting to attract an audience. Alison hoped the cops would show up soon. When Mr. Freed got too worked up, a sheriff’s deputy usually came to get him and let him sleep it off in a nice warm cell. But no cops were in sight.

“Tell it like it is, Barry!” someone yelled, just to rile him up.

Alison ground her teeth. That was just mean. It was really no better than that rotten Matt picking on Arnold just because he was a brainiac and had a hard time making friends.

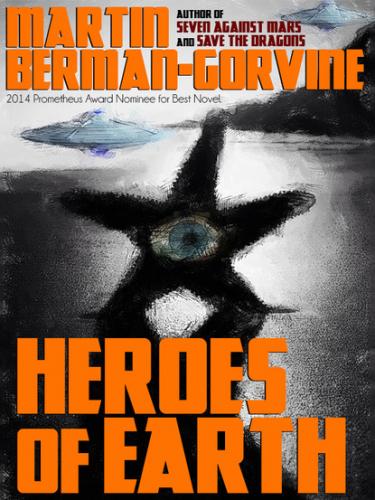

“You bet I’ll tell it like it is!” The old hippie had jumped up on the Birches’ white picket fence, which teetered dangerously beneath his weight. “There ARE no High Ones! It’s all a lie! There’s no such thing as big blue starfish, or little green men, either! They faked the moon landing just to make people think there could be aliens, so they’d have an excuse to crush the Movement. Then they got everyone hooked on their mind-control devices, which they have the chutzpah to claim are ‘neural readers’ that are an educational gift from the imaginary aliens!”

That hit a little too close to home. Alison seized the chance to slink away. Her house was just the other side of Maddox Boulevard, the main road to the beaches on Assateague Island. In bleak autumn weather like this, of course, no one was heading out that way, and all the ice cream shops and tourist traps that gave the town a holiday feel in the summer were closed. A lot of the lifelong islanders, the “from-heres,” depended on beachgoers for their living but also resented all the noise and crowding they brought. Alison didn’t mind the summer crowds at all. When all those people came down from Baltimore and Washington, Chincoteague almost felt like home—her real home back in Pikesville.

Dad had fixed up their new house so it looked a lot like the old one, painted white with green trim. With the money he made at the fusion plant, he could have afforded instead to tear it down and replace it with a new house and a swimming pool in the backyard. But he wanted to keep it, because it was “historic,” meaning it was over a hundred years old, with a living room ceiling that bulged downward in the middle as if it was about to collapse, though Dad’s engineer buddy Bruce Nomura claimed there was no danger. This would have been more reassuring if Mr. Nomura had been a structural engineer instead of an expert on the High Ones’ nuclear fusion technology. If it was so safe, Alison wondered why it was so noisy. Sometimes she’d lie awake at night wondering if there were ghosts making all those creaks and groans, even though at seventeen she was much too old to believe in such things. Would I be happier if it was a burglar? she sometimes wondered, by daylight.

Alison let herself in with her key. Dad wouldn’t be home for another two hours at least, and it would be dark by then. She set a snack out for Arnold, who was doubtless daydreaming on his way home. Her little brother liked peanut butter sandwiches on whole wheat with sliced banana instead of jelly. She thought that was gross, but it reminded him of when Mom used to make them for him, back before she started spending the whole day in bed with her migraines. Then she tiptoed upstairs to peek into the master bedroom. Sure enough, Mom was lying in bed with the shades pulled and a damp washcloth over her eyes. Good, she’s asleep, Alison thought, but as she turned to go that familiar cranky voice started up.

“You’re not going to watch tri-vee before getting your homework done, are you, Allie?”

“Of course not, Mom.”

The graying head turned from side to side but the eyes never opened. Since they’d moved to Chincoteague Mom hadn’t found a hairdresser who could get her color right, or so she said, but Alison thought that since she’d gotten so much sicker over the past year she just didn’t care what she looked like anymore. And she looked like hell, with her face wrinkling up and her hair going wild as weeds in an untended garden. The darkness she craved could only hide so much, and then there was her B.O. Allie didn’t know how Dad could stand it. Basically it sucked having a mother with NINA—Network-Induced Neuronal Atrophy, a disease that struck fewer than one in a million n-net users. It was getting hard to remember what Mom had been like before, when she used to play her guitar and make Dad go out dancing with her. She’d taught Alison to play a little, but the guitar had sat untouched in a corner of the master bedroom ever since they’d moved to Chincoteague. Even if she’d