This one was nervous but not hungry. My stomach growled as we rode in. In response to the Lady Electra's imploring looks, I had pulled a corner of my mantle over my face and head, so I saw little as I was ushered inside the new house. I could smell bread baking and I was suddenly very hungry.

'The horses stay with us,' I said. Chryse asked, 'Travel sense or intuition?'

'Intuition,' I told him. Chryse nodded and lifted Electra down from the saddle. She was so muffled in wrappings that it would have taken a seer to identify her.

'No one's looking,' said the Asclepid patiently. Electra shed a few ells of peplos and shook her head. 'Oh, I'm so stiff!' she complained.

'Horses always come first,' I said. Diomenes and Eumides went out and shut the door behind them, leaving only two small openings to shed light on the interior, which was entirely empty and newly whitewashed. The floor was of beaten earth and I knew that horse dung and water was mixed with it to make a hard surface which can be swept. Our mounts added considerable flooring material as I taught Electra and Orestes how to unsaddle and rub down the beasts.

'You must always clean out the hoof,' I demonstrated, picking up Nefos' back foot. He did not like this but he had been tended before and was resigned to it - as long as I didn't extend the process unduly. 'Just pick out any mud or stones, and watch the creature's reaction. See, look at Nefos. His skin is twitching and his ears are laid flat. If I don't give him his hoof back, he's going to kick.'

He did, but I dodged, and the hoof hit the door, which boomed.

'Instructive,' said Electra. 'Now, Banthos, you're not going to kick me, are you?' She put her arms round the horse's neck and he lowered his muzzle and snuffled her hair. Being Banthos, he might have thought it was edible. But Electra was touched and proceeded to groom him to a gloss which the Amazon cavalry might have appreciated.

Orestes was willing, but not strong. Once we finished with the horses, our next need was water.

An amphora stood inside the door. I hefted it. It was almost empty.

'Will you go for water, or shall I?' I asked. Electra blushed fiery red, as though I had offered her a terrible insult.

'I will not,' she managed to say. Orestes was also staring at me. Deciding that all Argives were quite mad, I lifted the water jug to my hip.

'Take my veil,' she offered, draping it over my head. My arms were full of terracotta so I let it stay, walked into the square, and filled the jug from the well. There were ten men in the square, shepherds and farmers. They followed my every move, some levering themselves off their bench to try and stare through my veil. They talked about me as though I was not there, though luckily their dialect was so thick that I could not understand all the words. They seemed to be discussing my childbearing potential. They stared at me, those peasants, as though I was carrion and they were crows. Comforting myself with the reflection that I could kill any one of them with a single arrow, I paced back to the house and Electra let me in.

It was not at all amusing to be an Achaean woman. I resolved to stop doing this as soon as I could.

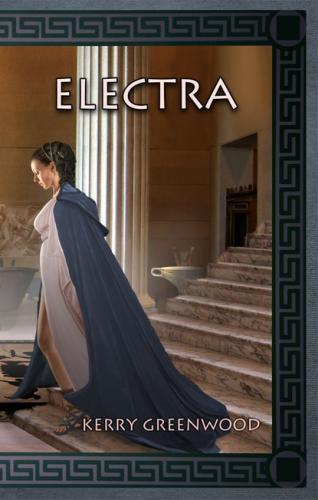

Electra

I had never ridden on a horse before. It was exhilarating, though I was still unsteady and I hadn't even dared to inspect my bruises. Orestes was interested in the conversation and looked well, though I kept listening for his cough. He had coughed all the time as a baby, until Neptha had declared that my mother would never raise him.

Banthos let me groom him. I found something very soothing in brushing the horse's coat, with a wisp of plaited straw, until it began to shine. It was as satisfying as raising gloss on worked leather, and the technique is the same, except that this was a living beast who enjoyed the attention. He turned around and nudged the hand to keep going even if the wrist was tired, which mine was.

I had become almost reconciled to poor mad Cassandra, who had been quite entertaining company during the day and very brave in the village, but then she suggested that I fetch water.

I just stared at her. She must have realised her error, because she went out herself. It probably isn't her fault - she is a barbarian, a stranger and a captive - but I didn't know what to say. Neither did Orestes. Slaves fetch water. Only slaves.

When she came back she seemed short of breath, but she didn't say anything, and we watered the horses. I found that Banthos could drink out of a dish, such a clever creature. That used up all the water, so Cassandra hoisted the amphora and went out again, unveiled. I heard silence fall in the square outside. This time she came slowly back, not hurrying at all.

'Didn't they stare at you?' I asked. She laughed.

'Oh, yes,' she said indifferently. 'I don't mind being stared at, as long as I can stare back, and not one of them would meet my eyes. Hecate is with me. They might have sensed that.'

'Hecate? You are a priestess of the Black Mother?' I pushed Orestes behind me. Hecate's worship includes human sacrifice.

'No. I was a priestess of Apollo - but I have belonged to the Gods since I was a child. The Gods of Troy are Gaia the Mother and Dionysos the Dancer. But the others are there if I need them,' she said, grimly pleased, and tipped some water into the dish to wash her face.

Diomenes and Eumides returned laden with bread and wine and a squashy basket which proved to be full of soft sheep's-milk cheese. We sat down on the floor and shared it out, and it was delicious. The wine was better than the night before and the bread was crisp and hot from the oven. I ate my share and gave Banthos a crust, which he took off my palm with great care. His lips were soft and he snuffled.

'Now, we're off to make spearheads,' Diomenes said. 'You can sleep, Maiden. Cassandra will watch.'

'So she will,' said Cassandra flatly. 'Be alert, friends, I don't like this place.'

'I'm coming too,' Orestes insisted.

'No, you'll stay here with me,' I said. He set his jaw and said, 'I am a man. I should be with the men.'

Diomenes knelt down until he was eye-to-eye with the boy. 'Possibly, little brother, but not this time. If you are lucky enough to travel with a prophetess, then it is wise to listen to her. She says this place is unsafe. Therefore, you will stay here with the women, on guard. You have your knife?'

Orestes nodded, one small hand to his hip. He had a dagger such as is used at feasts to cut one's meat. It was a present from the King; bronze work of Mycenae, set with running bulls. A pretty toy for a lady. A weapon for a boy.

Cassandra, noticing me vainly trying to order my hair, took the comb from me and in a few rapid strokes had it tamed and coiled. She divided it into three strands and began to plait it, quickly and without pulling. I wondered that someone who could not sew could be so deft.

'I used to plait my little sister's hair,' she said, looping the ends back through the tail.

'What was her name?'

'Polyxena. My doomed little sister.'

'What happened to her?'

'Agamemnon sacrificed her on the grave of Achilles.'

'Then we are bound together,' I reasoned.

'How?' She did not sound either friendly or unfriendly.

'The same man sacrificed my sister Iphigenia for a wind to Troy, and they told us that she was going to be married to Achilles. She died, like your sister.'

We did not say anything, but our hands crept out and clasped, warmly, in the darkness. We sat like that for a long time, then I lay down to sleep and she sat upright, watching, in the night.

The attack came without warning. I was jolted and rolled face down on the floor, breathing mud. I heard Cassandra shout a sentry's warning like a soldier. 'Ware enemies!' and there was a solid thud