The first Forum Against Extradition is held in Medellín. Pablo invites me to sit at the main table beside the priest Elías Lopera, who is sitting to his right. There, for the first time, I hear his fiery nationalist speech against that legal concept. Over time, the fight against extradition will become his obsession, his cause and his fate, the plight of an entire nation. It will affect millions of our countrymen and claim thousands of victims, and it will be a cross for him and for me to bear. In Colombia, justice almost always takes twenty years or more in coming—if it comes at all, because along the way it’s often sold to the highest bidder. The system is designed to protect the criminal and wear down the victim, which means that someone with Pablo’s financial resources is destined to enjoy the most egregious impunity throughout his life. But a black cloud has now appeared, not only on his horizon but on that of everyone in his trade: the possibility that any accused Colombian can be requested for extradition by the U.S. government. In other words, they could be tried in a country with an efficient judicial system, high-security prisons, multiple life sentences, and the death penalty.

In that first forum, Pablo speaks before his peers using much more belligerent language than I have heard from him. He doesn’t hold back in his fierce attacks on the rising political leader Luis Carlos Galán. Pablo berates the presidential candidate for having expelled him from his movement, Renovación Liberal (Liberal Renewal), whose main cause is the fight against corruption. In 1982, after Galán found out where Pablo’s money really came from, he had notified Escobar of his expulsion—though without mentioning him by name—in front of thousands of people gathered in Berrío Park in Medellín. As long as he lives, Pablo will never forgive him for that.

I had met Luis Carlos Galán twelve years before in the house of one of the nicest women I ever remember meeting: the beautiful and elegant Lily Urdinola, from Cali. I was twenty-one years old, and I had just divorced Fernando Borrero Caicedo, an architect who looked exactly like Omar Sharif and was twenty-five years older than me. Lily had just separated from the owner of a sugar mill in the Cauca del Valle, and now she had three suitors. One night she invited them all to dinner, and she asked her brother Antonio and me to help her choose among them. There was the Swiss millionaire who owned a bakery chain, the rich Jewish owner of a clothing chain, and the shy young man with an aquiline nose and enormous blue eyes whose only capital seemed to be a brilliant political future. Although that night neither of us voted for Luis Carlos Galán, a few months later, at twenty-six years old, the quiet young man with light eyes became the youngest minister in Colombia’s history. I never told Pablo about this “defeat,” but for the rest of my life I would regret not having given my vote to Luis Carlos that night, because if Lily had let him court her, between the two of us I’m sure we could have fixed that blessed problem between him and Pablo, and thousands of deaths and millions of horrors could have been avoided.

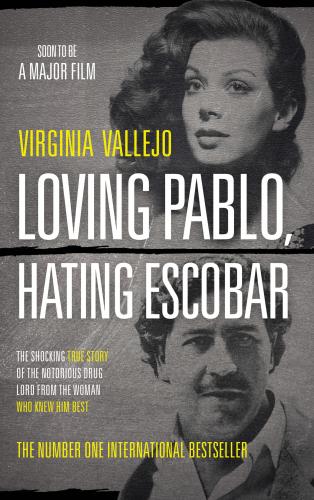

The photograph of Pablo and me at the first Forum Against the Extradition Treaty becomes the first of many to document the beginning of the most well-known part of our relationship. A few months later, the magazine Semana will use it to illustrate an article on “the paisa Robin Hood,” and with that generous description, Pablo will begin to build his legend, first in Colombia and then in the rest of the world. After that, in all our encounters, Pablo will greet me with a kiss and a hug followed by two spins, and then he’ll always ask me:

“What are they saying in Bogotá about Reagan and me?”

And I’ll tell him in detail what everyone thinks of him, because what they say about President Reagan is only interesting to Nancy’s astrologist and the Republican congresspeople in Washington.

For the second Forum Against the Extradition Treaty we travel to Barranquilla. We stay in the presidential suite of a recently opened grand hotel, instead of El Prado, one of my favorites. Pablo likes only the most modern things, while I like only the most elegant, and we will always argue over what he considers “antiquated” and what I see as “magical.” The event takes place at Iván Lafaurie’s splendid residence. The house was beautifully decorated by my friend Silvia Gómez, who has also done all my apartments since I was twenty-one.

This time, the media has not been invited. Pablo tells me that the poorest of the participants has ten million dollars, while the fortunes of his partners—the three Ochoa brothers and Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha, “the Mexican”—plus his own and Gustavo Gaviria’s, total several billion dollars and far exceed those of Colombia’s traditional tycoons. While he is telling me that almost all the attendees are members of MAS, I’m reading disconcertion in the expressions on many faces when they see a well-known TV journalist is present.

“Today you will witness a historic declaration of war. Where do you want to sit? In the first row down below, looking at me and the bosses of my movement, who you met in Medellín? Or at the main table, looking out at the four hundred men who are going to bathe this country in blood if that extradition treaty is approved?”

As I’m starting to get used to his Napoleonic speaking style, I choose to sit at the far right of the main table. It’s not that I want to get to know those four hundred faces of the new millionaires who could eventually replace—and even guillotine—my powerful friends and ex-lovers in the traditional oligarchy (a thought that produces mixed emotions in me, from deepest fear to the most exquisite delight). Rather, I want to try to read on those hardened and leery faces what people really think of the man I love. While I don’t like what I see, what I hear makes my blood run cold. I don’t know it, but this starry night, in this mansion surrounded by gardens beside the Caribbean Sea, is the baptism by fire of the Colombian narco-paramilitarism. And I am attending it as the only woman, the only witness, and the only possible historical chronicler.

When the speeches are over and the forum ends, I descend from the stage and walk toward the pool. Pablo stays, chatting with the hosts and his partners, who all congratulate him effusively. A crowd of curious people surrounds me, and several of the attendees ask me what I’m doing here. One man, who looks like a traditional landowner and livestock breeder from the Coast—with one of those last names like Lecompte, Lemaitre, or Pavajeau—emboldened by rum or whiskey, says in a loud voice for all to hear:

“Now, I’m too old for one of these kids to come in and tell me who to vote for! I’m a godo [member of the Conservative Party], the old-fashioned and lifelong sort, and I’m voting for Álvaro Gómez, period! That’s a serious guy, not like that rascal Santofimio! Where does this Johnny-come-lately Escobar get off, thinking he can barge in and give me orders? Does he think he has more money and more cattle than me, or what?”

“Now that I know you can get a TV star with the coke money, I’m going to get rid of Magola, my wife, and marry the actress Amparito Grisales!” brags another one behind me.

“Does this poor girl know that the guy was a ‘trigger man’ who’s got more than two hundred deaths under his belt?” taunts