Nobody moved. They preferred to die than denounce anyone.

When it was time to bury the dead, a soldier found a baby that was still alive. He asked Villa what to do with him. “Are you going to take care of him?” Villa asked. When he didn’t get a response, he ordered the soldier to kill the baby.

Colonel José María Jaurrieta, the Centaur of the North’s loyal secretary, wrote that this massacre made him think of Dante’s inferno. The horror of those 90 women massacred by Villista bullets stayed in his memory forever.

“It was a scene out of Dante. I doubt whether any pen can faithfully describe the visions of suffering and terror that took place that morning of December 12, 1916. Wailing! Blood! Despair! Ninety sacrificed women, piled up one on top of the other, with skulls shattered and chests perforated by Villista bullets.”

Friedrich Katz also cites Jaurrieta, who suggests that Villa did it out of self-defense. But not quite. Maybe one of the soldaderas did try to kill him, but he eliminated all of them. In his book, Pancho Villa, Friedrich Katz explains: “The massacre of these soldaderas and the rape of the women of Namiquipa were the most serious atrocities that he committed against the civilian population in his years as a revolutionary. They constituted a fundamental change in his behavior after his defeat in 1915. Until that moment, practically every observer had been impressed by the discipline that Villa maintained and by his efforts to protect civilians, especially the members of the lower classes.”

Soldaderas ended up with the worst of the revolution. We’re told this by the painter Juan Soriano.

Soriano is the only one among the intellectual class who has revealed that his mother was a soldadera. Amelia Rodríguez Soriana, alias “The Lioness,” followed her husband Rafael to the north. Near Torreón, according to Soriano, the women stayed in the rear with the assistants and the equipment. Since combat seemed to go on forever, some of the young men started playing the guitar and dancing with the soldaderas. Soriano’s mother told them: “Don’t dance. Over there they’re risking their lives in battle and here you are making a big racket. If they find out, they’ll kill you.”

Said and done, the soldiers returned and killed their women as well as the gallant young lovers.

In 1916, Elisa Grienssen Zambrano, 13 years old, became “The Provocadora.”

The American troops entered the town of Parral, Chihuahua, in search of Pancho Villa after his attack on Columbus, New Mexico. When the girl saw that no one said anything, she yelled at the mayor: “What? Aren’t there any men in Parral? If you can’t kick them out of here, we, the women of Parral, will.”

Elisa Grienssen got the women and children together. She asked them to bring whatever was at hand: weapons, sticks and stones. Infuriated, with their arms in the air, the women surrounded the American commander and forced him to shout: “Viva Villa, Viva México!” as he ordered a retreat.

If Villa, in the north, was the scourge of women, Zapata on the other hand, never humiliated them, as John Womack relates in his book Zapata and the Mexican Revolution: “In Puente de Ixtla, Morelos, the widows, wives, daughters and sisters of the rebels formed their own battalion to ‘seek vengeance for the dead.’ Under the command of a stocky former tortilla-maker by the name of China, they carried out savage incursions throughout the Tetecala district. Some dressed in rags, others in elegant stolen clothes—silk stockings and silk dresses, huaraches, straw hats and cartridge-belts—these women became the terror of the region. Even De la O treated La China with respect.33

Genovevo de La O was one of the chief leaders of the Zapatista insurrection in central Mexico.

Josefina Bórquez, in her account Hasta no verte Jesús mío, states that Emiliano Zapata treated women very well. To back it up, she describes how she and four married women were detained in Guerrero—a Zapatista nest—between Agua del Perro and Tierra Colorada.

The Zapatistas came out to meet them. They took them to General Zapata himself. He asked them if they had machine guns and Josefina answered no to all his questions. Zapata put her at ease: “Well, you’re going to stay here with us until the detachment arrives.”

They remained in the camp for fifteen days and were treated well. Zapata ordered a tent set for them and saw to it that no provisions were lacking for them: sugar, coffee, rice. The women ate a lot better than with the Carrancistas.

When General Zapata found out that the Carrancistas were in Chilpancingo, he told the women that he would take them himself. He took off his general’s uniform, put on cotton trousers and escorted them unarmed. He gave orders to his soldiers: “Stay behind. Nobody goes with me. I want to show the Carrancistas that I fight for the Revolution, not to take possession of their women.”

At the door of the barracks, they asked him, “¿Quién vive? Who goes there?” and he answered: “Mexico.”

The sentry asked: “Who are you?”

“Zapata.”

“You’re Emiliano Zapata?”

“I am.”

“Well, I find it strange that you come without protection.”

The father of Josefina Bórquez came out.

“Yes, I come alone escorting the women that I am about to deliver to you. No one has touched them; I bring them back to you exactly as we found them. You should vouch for the four married women because they told me they were taking care of Josefina Bórquez. You have to make sure that the married ones won’t suffer any consequences at the hands of their husbands.”

“Yes, very well.”

Zapata turned around and disappeared.

Josefina Bórquez, alias Jesusa Palancares, also tells of how she confronted Venustiano Carranza at the Palacio Nacional, in Mexico City. “Goat Whiskers” had promised to pay military wages and the pensions for the widows and the soldaderas, but at the last moment he changed his mind:

“If you were old, the government would give you a pension, but because you’re very young and any day you’ll marry again, your dead husband shouldn’t have to support the new husband you’ll soon have.”

José-Jesusa, enraged, tore her legal documents and flung them toward Venustiano Carranza’s face.

“Oh, you’re a coarse woman!”

“You are the one that is coarse! You steal money from the dead.”

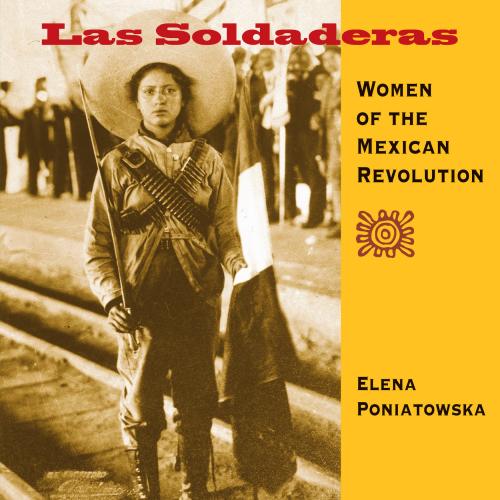

In the photographs of Agustín Casasola, the women—with their percale petticoats, their white blouses, their delicate washed faces, their lowered gaze that hides the embarrassment in their eyes, their candor, their modesty, their dark-skinned hands holding bags of provision or handing a Mauser to their men—don’t look at all like the coarse, foul-mouthed beasts that are usually depicted by the authors of the Mexican Revolution. On the contrary, although they’re always present, they remain in the background, never defiant. Wrapped in shawls, they carry both the children and the ammunition. Standing or sitting by their man, they have nothing to do with the greatness of the powerful. Quite the opposite, they are the image itself of weakness and resistance. Their smallness, common to the Indians, helps them survive. On the bare ground, or sitting on top of the train cars (the horses are transported inside), the soldaderas are small bundles of misery exposed to all the severities of both man and nature. In La Cucaracha, actress María Felix plays the butch—with a cigar in her mouth and a raised eyebrow—who slaps men left and right and carries a jug of aguardiente strapped around her back and shoulder. Did such a soldadera ever exist? There’s no proof of it. Instead,