I continued through the Hall, reading the plaque inscriptions. Some of the more recent ones were far from impressive. Arky Vaughan’s: Homered Twice in 1941 All-Star Game. Wow. And Ernie Lombardi, who according to the tablet author suffered from Slowness Afoot. So much for my “fleet-of-foot” expectations.

I next went into the three-story brick structure that housed the Baseball Museum. I felt this was where I belonged, an artifact from another era.

I was pushed along by the crowd into the Modern Baseball room. Baseball kitsch is more like it. The floor was covered with Astroturf; the green crinkly plastic looked like the stuff used to line Easter-egg baskets and made a crunching noise with each footstep that fell on it. The walls were lined with garish uniforms cased in chrome and glass: the Seattle Pilots uniform with gold braid and epaulets, the Chicago White Sox short-pants outfit, the Houston Astros uniform with horizontal stripes of Day-Glo yellow and orange. This wasn’t where I belonged.

As soon as I could, I sidled my way out of the crowded room. The nearest exit led to a staircase that I slowly climbed to the third floor. The crowd was much sparser here, and the exhibits much older. Sturdy oak display cases sat in neat rows on quiet, mottled beige carpeting. Fading photographs and browning prints hung on the walls in dark wood frames.

The first display I encountered was a long wall covered with a century of baseball cards. I’d forgotten how far back those cardboard icons went. Sepia studio portraits from the 1880s showed players frozen in carefully set “action” shots, reaching up to catch baseballs hanging from visible strings.

Cards from the turn of the century were in bold primary colors. Some of them seemed strangely familiar to me, and I felt certain that as a boy I had seen them when they were clean and uncreased, fresh from a package of candy or tobacco.

A decade later, the images were pastel-colored drawings of hatless ball players. Some were so crudely sketched and colored that they looked like comic strip characters. I started to play a game of seeing if I could identify a player by his picture before looking for his name at the bottom of the card. I picked out the faces of Tris Speaker, Smoky Joe Wood, and Jake Stahl; when I checked the bottoms of the cards I noticed their formal names were used—Tristram, Joseph, Jacob.

I was batting about .500 in the identification game when I came to a narrow-faced, wide-eyed player with sandy hair. He looked far too young to be in the big leagues. Drawing a blank on him, I glanced down for the name. Michael Rawlings. I looked back at the picture, and startled some bystanders by exclaiming, “Hey! That’s me!” The name wasn’t quite right—my given name is Mickey, not Michael—but it was me all right. Did I really ever look that young? Below the name was Boston (Am. L.). I was tempted to call everyone in the room over to see my card. I’m in the Hall of Fame!

I continued to scan the other cards, eager to pick out old teammates and friends. Every couple of minutes I’d glance back to check that my own card hadn’t vanished.

Most of the prints in this series showed the players’ portraits against a solid red background. One had a dark blue setting: Harold Chase, New York (Am. L.) whose rust-red hair required the different backdrop. Another’s color scheme made me wince in its similarity to the Houston Astros uniform I had seen downstairs: a head of blazing orange hair was set against a bright yellow background. The face under the hair was even more boyish than the one that appeared on my card. The name read John Corriden. John Corriden ... Red Corriden? Of course it was Red—with that hair color who else could it be?

I thought I had forgotten Red Corriden. But he must have lived on in some corner of my brain, because memories that I hoped were buried in 1912 now came roaring to mind.

Chapter Two

The Yankee Flyer finally screeched into South Terminal Station at 5:22, three hours and twenty-two minutes after the scheduled start of the Saturday game against Detroit. The train should have brought me to Boston in time for batting practice, but a derailment near Bridgeport voided the timetable.

Because I was so late, a cab seemed more a necessity than an extravagance. I hustled out of the station with a suitcase in one hand and a canvas satchel in the other. I ran up to the first taxi at the cab stand. “Can you take me to Fenway Park?”

The driver stood with one foot on the passenger side running board. His response seemed to come from the black Dublin pipe rooted in his mouth. “Do ye suppose I’m in this business if I can’t find Fenway Park, now?” I gave the cabbie a sheepish half smile and threw my bags on the back seat of the dust-spattered Maxwell. While I followed them in, the driver went to the front of the car and turned the starter crank until the engine coughed to life.

As the taxi clattered down Commonwealth Avenue approaching Governors Square, the heavy traffic coming the other way suggested the game had already ended. The cab driver’s next question confirmed it. “Now why would ye be heading to the ballpark with the game already over?”

“Well ... the Red Sox just bought my contract—from Harrisburg. I have to report to them today ... to play baseball ... I’m a ball player.”

“Are ye now? And what position might ye play?”

A simple enough question, but it threw me for a loss. “Well ... I play just about everywhere ... except pitcher. I’ve caught a few times ... but I’m not really a catcher. I guess I’ll play either outfield or infield someplace.”

The cabbie didn’t ask any more questions, and I was content to keep my mouth closed. The wheels of the passing carriages and automobiles were churning up dried horse manure into a fine powdery mist that rushed at me through the open cab. The biting spray made talking a distasteful labor and added another layer of filth to the gritty film of soot that had been wafted onto me by the Flyer locomotive. Late, dirty, and smelly—what a way to start a new job.

“Well, here ye are me boy. Good luck to ye.”

I paid the driver, hopped out of the taxi, and took my first look at Fenway Park.

Last year I had gotten into fifteen games, the full scope of my major-league career so far, with Boston’s National League team, the Braves. Home field was the South End Grounds on Walpole Street. It was a cramped, rickety wooden stadium badly in need of renovation or an extensive fire.

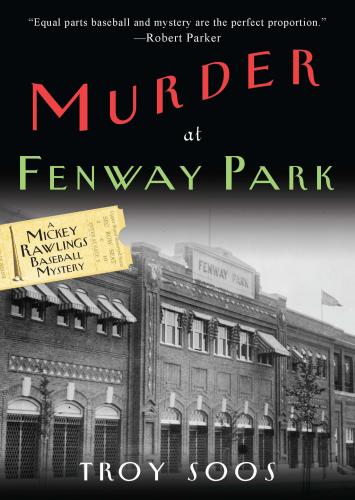

Now I gazed in awe at an enormous new ballpark. Fenway Park had opened just a week before as one of the most modern arenas in baseball. With my eyes fixed on the towering structure, I drifted along the sidewalk, my hurry to get there forgotten.

There was a simple majesty to the ballpark’s construction. The crisply new red bricks of the high walls; the graceful beckoning arches over the entrances, each with a gray stone inlay at its crest; and crowning it all, a massive white slab atop the left field wall with FENWAY PARK chiseled on it in clean sharp lines. It looked to be a baseball cathedral.

I finally hoisted my bags and strode purposefully to the main entrance. Even the stragglers had left the park by now. The only person visible was a slender, silver-haired attendant who wore his navy blue uniform with a dignified authority.

Respectfully, I called out, “Excuse me! Could you let me in please?”

The attendant walked to the gate at a deliberate pace and politely declined my request. “I’m sorry. I can’t let anybody in here.”

“But I have to get in. I have to see the manager. I’m his new—” Again I wished I could have said “shortstop” or “left fielder,” but I could only finish the sentence by spitting out, “—ball player.”

The attendant glanced down at my bags and appeared to notice the three weathered bat handles sticking out of my satchel. Looking back up, he scrutinized my face and announced, “You’re Mickey Rawlings.” The tone of his voice suggested that I couldn’t possibly be Mickey Rawlings without his say so.

“Yes! Did they tell you I was coming?”

“No,