Today’s Jamaicans are the descendants of the Amerindians, the European colonists, the African slaves, and those who came later—Germans, Irish, Indians, Chinese, Lebanese, Syrians and Arabs.

Jamaica’s cuisine is the product of this diverse cultural heritage, and its food tells the story of its people. The cuisine’s unique flavors include mixtures of tanginess and burning hot pepper, the rich complexity of slowly stewed brown sauces, the spice of intense curries and the cool sweetness of its many tropical fruits.

Some of the most authentic examples of the island’s food are found in the most humble roadside eateries. And some of its best new fusions can be discovered in the island’s hotels and restaurants, being prepared by chefs who are joining traditional flavors with new ingredients.

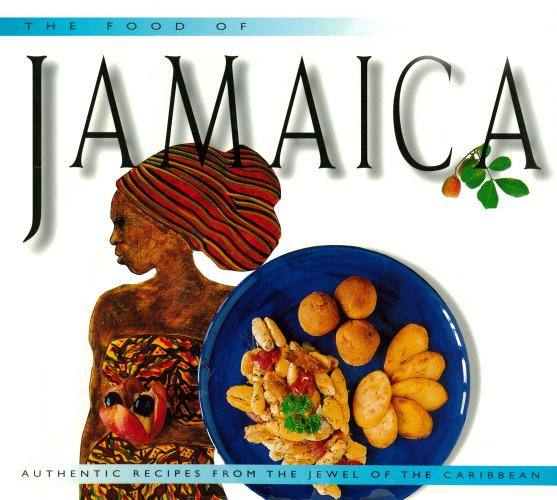

This book aims to unravel Jamaica’s many-faceted culture and make it come alive for you. Whether you have visited often or never, these pages will cast light onto the island’s history, culture and, most of all, its cuisine. The recipes offered here run the gamut of the island’s offerings—from the most humble, but tasty, fried bread to its spiciest jerk chicken.

Perhaps by reading in these pages about Jamaica’s history, landscape, people and food, you will begin to share the pleasures of this multilayered island paradise, which is as complicated as its stormy history and many cultures, as beautiful as its rare wildlife and flowers and as unforgettable as its easy yet knowing Caribbean smile.

Native Soil

An Eden-like land of fertile fields and sandy beaches

From its primal beginnings, Jamaica was ripe for harvest. “The fairest land ever eyes beheld,” scribbled an eager new arrival in his journal. “The mountains touch the sky.” This visitor was hardly the last to be awestruck by Jamaica’s beauty, but he was probably the first to write anything down. The year was 1494. The visitor was Christopher Columbus on his second voyage to the New World, and he had come to claim this “fairest land” for God, for himself, and for Spain.

Hardly a set of eyes has settled on these mountains, waterfalls and hills that roll and dive down to the palm-fringed sand, without the beholder thinking he was seeing the biblical Garden of Eden. It is important, however, to understand the interworkings of nature and man that have shaped Jamaica.

Known to Jamaica’s first residents, the Arawaks, as Xaymaca (land of wood and water), the island was just that before the arrival of Europeans. It featured the two elements in its name—both important to the Arawaks and anyone else hoping to settle here—but little else except a tangle of mangroves. For all the human suffering they brought, the Spanish and British also covered the island with colorful, edible vegetation. The tropical fruits and flowers of this beautiful island are transplants from places like India, China, and Malaysia. Still, nature has been bounteous, offering its many colonists fertile fields in addition to beauty and other resources. The colonizers visited many other Caribbean islands, leaving most of them as spits of sand dotted with a few palm fronds. But in Jamaica they stayed, shaping the island to their own image.

Collecting and counting bunches of bananas to fill the cargo holds of boats destined for North America. On the return trip the boats were filled with a very different sort of cargo—tourists escaping the bleak northern winter.

Located in the western Caribbean, Jamaica is larger than all but Cuba and Hispaniola. Millions of years ago the island was volcanic. The mountains that soar to nearly 7,500 feet are higher than any in the eastern half of North America. These peaks run all through the center of Jamaica. The island has a narrow coastal plain, no fewer than 160 rivers and a dramatic coastline of sand coves. Much of Jamaica is limestone, which explains the profusion of underground caves and offshore reefs—not to mention the safe and naturally filtered drinking water that first impressed the Arawaks. In the mountains of the east (the highest, Blue Mountain Peak, rises to 7,402 feet) misty pine forests and Northern Hemisphere flowers abound. Homes there actually have fireplaces, and sweaters are slipped on in the evenings. In places, the mountains plunge down to the coast creating dramatic cliffs.

The hotter, flatter southern coast can look like an African savanna or an Indian plain, with alternating black and white beaches and rich mineral springs. There are tropical rain forests next to peacefully rolling and brilliantly green countryside that, save for the occasional coconut palm, could be the south of England. It is surely one of history’s quirks: many parts of Jamaica (a small place by the world’s standards) resemble the larger countries from which so much of its population hails.

In the heyday of the British Empire, flowering and fruit trees were brought from Asia, the Pacific and Africa; evergreens came from Canada to turn the cool slopes green; and roses and nasturtiums came from England. The ackee, which is so popular for breakfast, came from West Africa on the slave ships. Breadfruit was first brought from Tahiti by no less a figure than Captain Bligh of the Bounty. Sugar cane, bananas and citrus fruits were introduced by the Europeans.

A late nineteenth-century print of Muirton House and Plantation, Morant Bay.

Jamaica did send out a few treasures. One of the island’s rare native fruits, the pineapple, was sent to a faraway cluster of islands known as Hawaii. Its mahogany was transplanted to Central America. There are varieties of orchids, bromeliads and ferns that are native only to Jamaica, not to mention the imported fruits like the Bombay mango that seem to flourish nowhere else in this hemisphere.

The island is clearly a paradise if you are a bird, simply based on the number of exotics that call it home. Native and migratory, these range from the tiny bee hummingbird to its long-tailed cousin the “doctor bird” to the mysterious solitaire with its mournful cry. Visitors to Jamaica’s north coast become acquainted with the shiny black Antillean grackle known as kling-kling, as it gracefully shares their breakfast toast. And those hiking through the high mountains can catch a glimpse of papillo homerus, one of the world’s largest butterflies. Unlike most of the population, animal or human, papillo homerus is a native.

You don’t have to rough it to see gorgeous views in the Blue Mountains. Spectacular scenery can he viewed from the roads that wind across the region.

A tropical climate prevails in Jamaica’s coastal lowlands, with an annual mean temperature of about 80 degrees Fahrenheit (26.7 degrees Celsius). Yet the heat and humidity are moderated by northeastern trade winds that hold the average to about 72 degrees Fahrenheit (22.2 degrees Celsius) at elevations of 2950 feet (900 meters). Rain amounts vary widely around the island, from a mere 32 inches annually in the vicinity of Kingston to more than 200 inches in the mountains in the northeast. The rainiest months are May, June, October and November with hurricane season hitting the island in the late summer and early autumn.

The Jamaican economy relies heavily on agriculture, though the island is blessed with mineral deposits of bauxite, gypsum, lead and salt—the bauxite constituting one of the largest deposits in the world. Despite its significant diversification into mining, manufacturing and tourism, the island continues to struggle against a budget deficit each year. Agriculture still employs more than 20 percent of the Jamaican population. While sugarcane is clearly the leading crop, other principal agricultural products include bananas, citrus fruits, tobacco, cacao, coffee, coconuts, corn, hay, peppers, ginger, mangoes, potatoes and arrowroot. The livestock population takes in some 300,000 cattle, 440,000 goats, and 250,000 pigs.

This is the lush backdrop to life on this Caribbean island. Of course, no profile of Jamaica would be complete without a description of its single most unforgettable resource: its people.

Out of