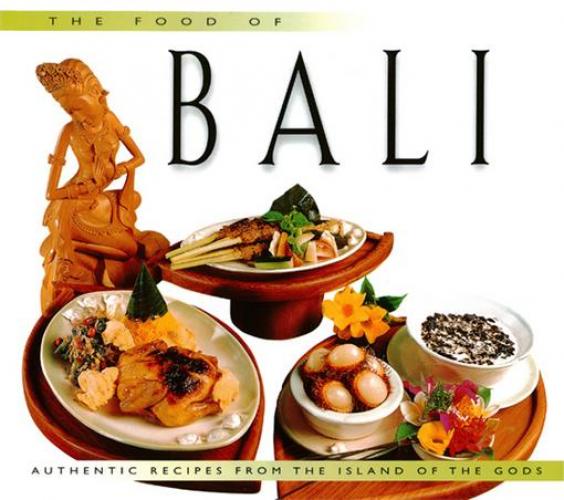

Balinese meal of Sate Lilit (top), Festive Turmeric Rice, Urap and Grilled Chicken (right) and Black Rice Pudding with fresh rambutans (left).

Garden of the Gods

Tropical bounty in the shadow of volcanoes:

geography, climate and cultivation

Bali's landscape is characterized by abundance: thousands of verdant rice fields, graceful coconut palms and a myriad of tropical fruit trees, coffee plantations and even vineyards make up the cultivated areas. On the slopes of the mountains, lush tangles of vines and creepers link huge trees, many dripping with orchids and ferns. It is not hard to understand why the island is often described as "the morning of the world," "island of the gods" and "the enchanted paradise."

Lying between 8 and 9 degrees of the equator, Bali is only 143 kilometres east to west and 80. 5 kilometres north to south. Its extraordinary richness is the result of a combination of factors. The island, and most of Indonesia, lies above the join of two of the earth's seven tectonic plates, and the toweling volcanoes that dominate the landscape are responsible for much of Bali's fertility. Occasional eruptions, while potentially destructive, paradoxically increase fertility as they scatter rich ash and debris over the soil.

Rice terraces cannot function without irrigation. The irrigation cooperatives, or subaks, ensure that sufficient water is available year-round.

The tall mountains (Gunung Agung is 3,142 metres and neighbouring Gunung Batur 1,717 metres) help generate heavy downpours of rain, which collects in a number of springs and lakes. The water flowing down the mountain slopes creates rivers that carve deep ravines as they make their way down to the sea.

Bali experiences two seasons, a hot wet season from November to March, and a cooler dry season from April to October. Long periods of sunshine and adequate rainfall create a monsoon forest (as opposed to rainforest, which grows in tropical regions without a dry season). Natural vegetation, however, covers only about a quarter of Bali (mainly in the west). The rest of the countryside has been extensively modified through cultivation.

The Balinese eat only very small amounts of meat, poultry or fish. Rice is the centrepiece of every meal, accompanied by a variety of vegetables, spicy condiments or sambals, crunchy extras such as peanuts, Crispy-Fried Shallots, fried tempeh (a fermented soybean cake) or one of dozens of types of crisp wafer (krupuk). Although rice is the staple, certain other starchy foods such as cassava, sweet potatoes and corn are also eaten, sometimes mixed with rice, not just as an economy measure (they cost less) but because they provide a variation of flavour.

Many of the leafy greens enjoyed by the Balinese are gathered wild, such as the young shoots of trees found in the family compound (starfruit is one favourite), or young fern tips and other edible greens found along the lanes or edges of the paddy fields. Immature fruits like the jackfruit and papaya are also used as vegetables. The Balinese cook uses mature coconut almost daily, grating it to add to vegetables, frying it with seasonings to make a condiment, or squeezing the grated flesh with water to make coconut milk for sauces that accompany both sweet and savoury dishes.

Although the seas surrounding the island are rich in fish, the Balinese, even those living near the coast, eat surprisingly little seafood. Mountains are regarded as the abode of the gods and therefore holy, while the lowest place of all-the sea-is said to be the haunt of evil spirits and a place of mysterious power. On a more pragmatic level, the coastline of Bali is dangerous for boats and possesses few natural harbours.

The majority of the fish caught are a type of sardine, tuna and mackerel. Fresh fish is available in coastal markets and the capital, Denpasar, but owing to the limited availability of refrigeration, other markets sell these fish either preserved in brine or dried and salted, like ikan teri, a popular anchovy. Sea turtles have long been regarded as a special food and are eaten on festive occasions along the coast and in the south of Bali.

A beautiful tan-coloured cow with a white rear end that makes it look as if it has sat in talcum powder is being successfully raised in Bali, although beef itself is seldom eaten by the Balinese.

Pork is the favourite meat and appears on most festive occasions. Duck is also featured frequently on Balinese festival menus, usually stuffed with spices and steamed before being roasted on charcoal or minced to make satay.

The Balinese eat creatures that not everyone would consider candidates for the table, including dragonflies, small eels, frogs, crickets, flying foxes and certain types of larvae. Visitors are advised to dismiss any preconceptions and sample whatever is offered.

A balmy climate gives Bali an abundance of lush tropical fruit, ranging from familiar bananas to giant jackfruit and thorny durians.

Rice, the Gift of Dewi Sri

Soul food, the life force and

the rice revolution

Terraced rice fields climb the slopes of Bali's most holy mountain, Gunung Agung, like steps to heaven. When tender seedlings are first transplanted, they are slender spikes of green, mirrored in the silver waters of the irrigated fields. Within a couple of months, the fields become solid sheets of emerald, which turn slowly to rich gold as the grains ripen. Although irrigated rice fields cover no more than 20 percent of Bali's arable land, the overwhelming impression is a landscape of endless fertile paddy fields slash ed by deep ravines and backed by dramatic mountains.

Rice, the staple food of the Balinese, nourishes both body and soul. As elsewhere in Asia, the word for cooked rice (nasi) is synonymous with the word for meal. If a Balinese has a bowl of noodles, it's regarded as just a snack-with out rice, it cannot be considered a meal.

Red, black, white and yellow are the four sacred colours in Bali, each representing a particular manifestation of God. Although the majority of rice cultivated on the island is white, reddish-brown rice and black glutinous rice are also grown. The vivid juice of the turmeric root is added when yellow rice is needed on festive occasions.

A big plate of steamed white rice (usually eaten at room temperature) is the usual way rice is presented, although it appears in countless other guises. The most common Balinese breakfast is a snack of boiled rice-flour dumplings sweetened with palm sugar syrup and freshly grated coconut. All types of rice are made into various other sweet desserts and cakes.

Dewi Sri, the Rice Goddess who personifies the life force, is undoubtedly the most worshipped deity in Bali. The symbol representing Dewi Sri is seen time and again: an hourglass figure often made from rice stalks, woven from coconut leaves, engraved or painted onto wood, made out of old Chinese coins, or hammered out of metal. Shrines made of bamboo or stone honouring Dewi Sri are erected in every rice field.

Rice cultivation determines the rhythm of village life and daily work, as well as the division of labour between men and women. Every stage of the rice cycle is accompanied by age-old rituals. The dry season, from April to October, makes irrigation essential for the two annual crops. An elaborate system channeling water from lakes, rivers and springs across countless paddies is controlled by irrigation cooperatives known as subak Consisting of all the landowners of a particular district, the subak: is responsible not only for the construction and maintenance of canals, aqueducts and dams and the distribution of water, but also coordinates the planting and organises ritual offerings and festivals. The subak: system is extremely efficient and computer studies have found that, for Bali, its methods cannot be further improved.

Recently introduced rice varieties dictate that threshing takes place in the field.