I wake up gagging and run to the toilet, throwing up slippery water, and even when there is nothing left I do not feel better.

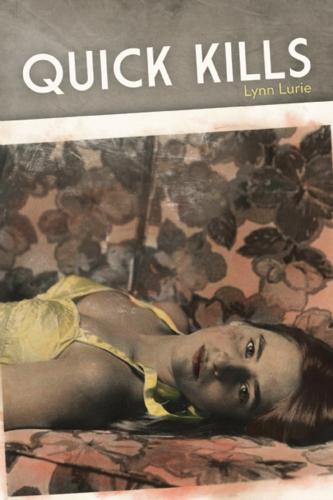

If Mother had asked to see the photographs the Photographer took I could not have shown her, not even one, as in almost every shot I am naked, and if I am clothed, I am either posed or making an expression that is inappropriate.

You said things to me, all sorts of things about my talent for photography. I now know it isn’t a talent. But this was not your crime. You were nearly the same age as Father.

Young girls, you said, fill canvasses, and gave me a book of photographs of paintings by Renoir and Gauguin. I liked the one by Renoir where the girls, I imagined them to be sisters, maybe even twins in identical party dresses, are draped alongside a grand piano. They are awkward in their bodies and it shows in the way their shoulders are positioned. Still, they know how to be watched.

Helen preferred a photograph of a painting by Gauguin. A bare-breasted woman looks directly at the painter without shame, but without joy either.

You catalogue the pictures of me and file the negatives in a locked metal cabinet, occasionally offering me a print if there is one you are especially proud of. Anything you gave me is gone now, as are mostly all of the photographs I took then. I never took one of your face and I always had my camera with me.

The Photographer and I shower in my parent’s bathroom just one time. Afterwards, I don’t know where to take him, so we go to dinner at the same restaurant we went to as a family on Sunday nights. Mother and Father would sit on the opposite side of the three of us. It always happened that Jake had to switch seats with Mother because he and Helen fought.

The Photographer is soon on his third bourbon.

I can’t eat what I always order, a small steak served on white bread where the blood from the meat turns the bread a brownish red. It had always been my favorite part of the meal, the doused bloody bread.

When we return as a family I tell the waiter steamed mussels. Mother notices but doesn’t ask why. I wish she had asked.

The first funeral I went to was on a day of record cold. The son delivered the eulogy, and when he finished, the family took seats in a perfect line in the back of a limousine. The old lady wore black satin gloves that disappeared into her coat sleeves. A caravan of cars followed with their lights on. A thin veil of snow hit our windshield and made an icy sound that echoed. The ice stayed ice, it didn’t melt or run.

No one took photographs even though he was painted back to life and his shirt collar was pressed. His cologne was so sweet it filled the funeral parlor and made my eyes tear. It seems now, because his frozen face is still so vivid, that I had been given a photograph of him as he lay there to take with me.

The coat Mother was wearing had once been alive. Silver fox, she said even though the fur was not silver and in picture books foxes were always red or brown. I rubbed my hand up and down her furry back until she pushed me away. I couldn’t help myself and kept going back. There was nothing about the feel that made me think it was something that had died or that had been killed. Finally she said loudly, go away. Others must have heard because at that moment the machine lifting the casket paused and the creaking stopped. The casket, now lightly dusted in white, was suspended above a gaping hole.

When he was lowered into the ground, each mourner was expected to throw a shovelful of dirt across the coffin’s shiny-varnished surface. My fingers were numb and Mother had forgotten my mittens. Still, she made me take the shovel, heavy with soil. The skin on the palm of my hand stuck to the handle the way my tongue stuck to cherry ice in summer. Helen turned away when I tried to give it to her. Rather than make a fuss, Mother took the shovel and passed it to the old man next to her. For that one time I wanted to be Helen.

The story we heard the rest of that winter and into the spring was how Patty Hearst had been kidnapped and sealed inside a coffin buried in the ground, even though she was still alive. The dead man looked so alive I was sure he, too, was breathing, that a mistake had been made. Even the newscaster couldn’t say if Patty Hearst was kidnapped or if she had gone willingly, and he didn’t answer the question everyone was asking, was she dead or was she alive?

Mother didn’t cry at the funeral, and when I asked why, she said there wasn’t anything that could have been done.

Father was a hunter. He turned into our driveway after having been away all weekend. Strapped to the roof of his gold-colored Buick were two dead deer. A trail of blood had hardened on the back windshield. I stared at the carcasses because at first I didn’t know what they were. At the same time Helen realized it, so did I. She screamed so loudly Mother rushed outside wearing her apron with the pine trees, her hands covered in ground meat. Daddy, Helen cried in the direction of the house, killed Bambi and her little sister.

He didn’t mount the heads or preserve the skins but he did gut them on our drive, the same drive where we rode our bicycles and played hopscotch after drawing the outline of the board with chalk. And even though he washed the pavement when he was finished, I was sure little pieces of bone or skin had caught in the rutted surfaces or settled in a shallow corner. I avoided all the corners, sure there was something remaining, a tuft of fur, a tooth. He scrubbed the car windows clean, the metal door handles, too.

Mother froze the deer meat in plastic but never made us eat it. She didn’t touch it either, except to fry it in the pan. Father was the only one.

Father wants to capture us as children and hang us on the wall above the love seat in the living room. To do this Mother takes us to the artist’s house to the part out back he calls his studio. We have to sit an hour a week and each of us goes on a different day because we can’t patiently wait our turn and then be poised and obedient.

Monday is my day. Monday mornings Mother worries about the creases in my jumper. I come to breakfast dressed but still she makes me remove the jumper and has me stand in my socks, shoes, and underwear at the ironing board while the maid runs the iron up and down the front of my dress. There are three pleats that begin at the collar and come to an end at the hemline, which is stitched in a zigzag of red. Father sips his coffee and watches me, not even pretending to read the morning paper. When Mother says the pleats are perfect, I put the dress on without waiting for it to cool. I would rather burn my skin than stand in front of Father for even one more second half-dressed.

Mother reminds me to hurry outside to the car as soon as the last bell rings. But I make her wait, having told my teacher Monday is a good day for me to wash the blackboards, which is why I am never the first one out and why, when I do appear, I am covered in chalk dust.

Mother doesn’t like the drive, especially in winter when it gets dark early. The unpaved road cuts through the woods where men come to shoot deer. I open the car window and listen for the sound of shots even though I have never heard any. Mother gets cold easily and insists I close the window. With my forehead pressed against the glass, I look for bloodstained patches of ground but I have never seen any.

The artist tells me to fold my hands and when he isn’t satisfied he comes over and bends down on one knee. Using both of his hands he moves mine, touching my fingers, placing them like tiny sculptures across my pink lap. It is each finger he wants to see. I don’t like him watching me so closely. Even so, I ask Mother if she has a ring I can wear. I imagine a pink stone in the shape of a diamond, but she doesn’t have a ring or any other jewelry, not for me.

Now when I think of my brother and sister as children, the faces I see are the ones the artist painted. Helen’s hair is parted slightly off-center. He captured the dazed look she already had in her