Several customers came and went, but they remained anonymous to him because they were disposed of quickly and easily.

He began studying some of the more recent additions to his stock. There was an old Kodak Autographic, a zither of ancient make, an almost new electric traveling iron. The things people lived by! But it was no use trying to recall the owners by the shapes of the things they had pawned. The objects were dead and characterless, had been unique and part of life only while they were in use. Oh, he was so tired, and it wasn’t even eleven o’clock. Forty-five wasn’t old . . . but he was old.

The young Negro wore gaudy clothes whose vividness was obscured by the grime and grease that made it look as though he had been wearing them without letup for years. He had the terrified, twitching face of a jackal, with pupils like tiny periods in his ocherous eyes. Under his arm was a small white table radio.

“Whatta you gimme, Unc, how much? Hey, dis worth plenty rubles. Dis a hot li’l ol’ radio, plenty juice. Got short wave, police call, boats from d’sea. Even get outer space on a clear night. Yeah, space, real-far space like from satlites an’ all. C’mon, Unc, make a offer. Hey, dis a hundred-dollar radio. How much you gimme? C’mon, dis powaful, clear tone, clear like a . . . a mother-f—n ol’ bell.” The saliva flew from his mouth as from a leaky old steam engine, and he kept snuffling through his nose and making queer jig steps for emphasis.

Sol took the radio and plugged it into the socket under the counter. He watched the light glow brighter as it warmed up, his face impassive while the young Negro in his filthy Ivy League cap twitched and muttered encouragement, as though the radio could redeem him.

“C’mon, baby, show d’man you power . . . blast him . . . Give him dat tone! Man, dat radio . . . O, dat mother . . .”

There came a few whistles, a loud electrical gibberish, and then the nerve-racking sound as of stiff cellophane being steadily crumpled by many hands. The youth stopped twitching and aimed his pin-point gaze at the radio. His mouth dropped open at the sound of his betrayal.

“Give you four dollars,” Sol said. Ah, our youth, the progenitor of our future. Maybe the earth will be lucky, maybe they will all be sterile.

“Hey, dat dere radio always play better dan dat,” he accused. “It mus’ be ’count of d’weather. Make it eight bucks. I mean, man, dat my mother’s radio!”

“Four dollars, take it or leave it.”

“Oh say, you tryin’ to bleed me, you suckin’ a man’s guts. I takin’ a awful chance hockin’ my mother’s radio. She sell me when she fin’ out.”

She ought to sell you. Sol massaged the bridge of his nose as he fumbled in his mind for the profit to all this.

“Six bucks?”

“Four.”

“C’mon, at least five skins, you bloodsuckin’ Sheeny!”

Sol felt a dangerous blue flicker behind his eyes. He began to move menacingly toward the little gate that led from behind the counter. “All right, animal, get out of here! Come on, out! Go peddle your junk in the street!”

“Okay, okay, mister, don’ go gettin’ all hot like. Gimme the four rubles, I take the four,” he said, his hands trembling and flying around with his need. “Hurry, hurry up, man, please.” His face showed the agony of some inner burning, an unbearable expression that filled the Pawnbroker with rage.

“Go on now,” Sol said, pushing the money at him. “And don’t go bothering me with your foul mouth any more. This is a place of business. I don’t have to have human rubbish in here.”

“Yes, man, O yes,” the youth said, not even hearing the Pawnbroker’s words. He took the money and gave it a quick kiss before stuffing it into his pocket. Then he cool-stepped out of the store with a beatific, lost smile on his writhing face. He left the pawn ticket on the floor behind him.

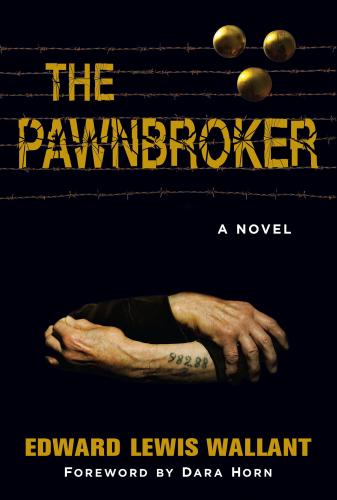

Sol felt the throbbing start of a bad headache. “It is getting hot,” he said aloud, as though to excuse the pain. He began rolling up the sleeves of his shirt for the first time that summer, disturbed at this first concession to the heat.

Jesus Ortiz came downstairs with a pair of suits on hangers. All morning he had sorted and stacked and labeled. He had looked at the clothing stacked in dusty hundreds to the ceiling of the stifling loft and each suit had seemed a building block for some odd edifice he was erecting without conscious design. Now he had reached a point where he was obsessed with perfection, and two ordinary suits had seemed to mar the aesthetic daze he worked in.

“These here suits, Sol,” he began, and then stared in puzzlement at the crudely tattooed numbers on his employer’s thick, hairless arm. “Hey, what kind of tattoo you call that?” he asked.

“It’s a secret society I belong to,” Sol answered, with a scythelike curve to his mouth. “You could never belong. You have to be able to walk on the water.”

“Okay, okay, mind my own business, hah,” Ortiz said, his eyes still on the strange, codelike markings. How many secrets the big, pallid Jew had! “I mean, like these here suits is like brand new,” he went on in an absent voice, no longer concerned with his mission. “They worth thirty-five, forty bucks easy. Got Hickey-Freeman labels inside.”

“I leave it to you, Ortiz. Be creative, use your own initiative,” the Pawnbroker said sardonically.

Ortiz just looked steadily at him for a minute before turning away with an equally secluded expression. He had secrets, too; secrets gave you a look of vast dignity, a feeling of power.

Just before twelve, as was his habit, Ortiz went out. He ate his own lunch in the cafeteria diagonally across the street and then bought Sol’s never-varying cheese sandwich and coffee, and brought them back to the store. He handled the traffic alone for some fifteen minutes while Sol sat in the little windowed office eating and staring out sightiessly through the glass like some exhibited creature from another clime. And while Ortiz worked, treating the predominantly Negro customers with a show of better-humored hardness than his employer’s, he was constantly aware of the odd, blind gaze on his back. He felt tense with a mysterious excitement, for the sense of his apprenticeship assumed an unfathomable importance then, seemed to possess the key to Sol’s buried treasure.

At least half the clocks hovered near one when three men came in pushing a motorized lawn mower. Sol stared at it for a moment, reminded of how incredible and silly his atmosphere was. Then he nodded in mild disgust, as though bowing to some nasty omnipotence. “Oh yes, here’s an item, fine, fine.”

He had seen two of the men around the neighborhood; the gaudy little Tangee in a wide-shouldered, checked suit, and Buck White, with his majestic tribesman face of almost pure black, who appeared elemental in his dignity until you noticed the foolish, childish dreaminess of his eyes. But it was the third man who took Sol’s attention. He was an oddly plain-clothed Negro in a shapeless, ash-gray suit and with a battered, styleless hat square on his head. With his clean white shirt and drab brown tie, he might have been some poor but discreet civil servant of decent education who was determined to avoid the Negro cliché in dress. Until you looked at his face, which was bony and gaunt and dominated by blue eyes filled with restless, darting menace. And in the presence of that face, the ridiculous transaction suddenly became oppressive out of all proportion.

“What’s this here worth, Uncle?” Tangee asked with a smile that was all flash. “Brand new, never been use. S’pose to have a real strong engine. I mean what do they get for these?” As he talked, his eyes, like those of his companions, roved over the vast assortment of merchandise with an insolent and covetous look.

“Where’d you get it?” Sol asked, rubbing his cheek.

“What kind of question is that? Why, it was a gift, man, a gift! I woulda return it to the store my friend bought it, on’y I was embarrass to ask him where. Didn’t want to let on I had no use for it,