ibidem-Press, Stuttgart

Table of Contents

Chapter 1. Introducing Egon Erwin Kisch, the Raging Reporter

Chapter 2. Notes on the Plays: Sources and Translation

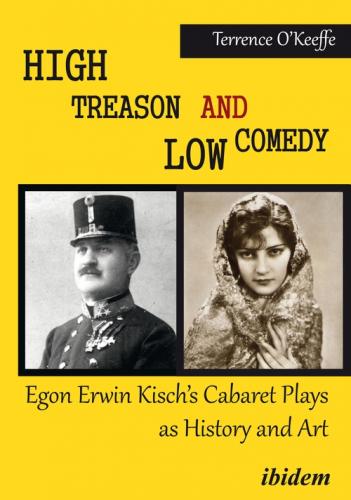

Chapter 4. Kisch and the Redl Case: Reportage into Melodrama

Chapter 5. The Ascension of Toni Gallows to Heaven

Chapter 6. Toni Gallows, a Real Prague Legend: Feuilleton into Comic Fantasy

Chapter 7. Kisch’s Career as Playwright

Chapter 8. Theatrical Context: German Playwrights and Weimar Comedy and Cabaret

Chapter 9. Afterlife of the Redl Story: Films, on the English Stage, a Slovak Novel

Chapter 10. The Toni Gallows Story on Film, the Prague Stage Again, and Television

Chapter 11. Transformations: History, Historical Fiction, and Fantasy

Bibliographical Note on earlier Kisch editions and the Kisch Gesammelte Werke

Preface and Acknowledgments

This book is the offspring of an earlier unfinished manuscript to which I had given the provisional title The Posthumous Lives of Colonel Redl. I came to the topic of Egon Erwin Kisch and the role he played in ‘breaking the Redl espionage case’ in 1913 (and continuing to write about it throughout his colorful career as a journalist) after seeing István Szabó’s film, Oberst Redl. “Excellent film,” I thought, but, as I began to read biographies of Redl and Kisch and the works of historians interested in the Redl affair, I realized the film was almost entirely fictitious, even fantastic, in its treatment of a scandal that had rocked the Habsburg military and political leaderships on the eve of World War One. From there my research spread into the many different social, political and cultural streams that wound their way through Kisch’s life. And I discovered that the Redl story continued to interest not just Szabó (70 years after the event) but a number of artists, right up to the present day.

The wave of First World War histories that began to appear in 2013 (many of which were ‘revisionist’ in their framing) usually mentioned the Redl case, sometimes in garbled fashion. So, Kisch and the espionage affair were still known and discussed in certain quarters, though, in English, much of this discussion was superficial or misleading. Although he had been well-known during the interwar years, Kisch’s reputation receded into an undeserved obscurity in the English-speaking world after his death in 1948. However, there are serious works that explain this trend and try to counter it. Kisch’s most recent major biographers (who published their books in 1997, one in German, the other in English) suggested that his earlier international renown had diminished in Western Europe, the UK, and the US as a result of the polarized opinions of the Cold War era (Kisch had been a prominent leftist activist during the last three decades of his life). The exception to this was Germany, where his works are still a subject of literary and historical discourse.

My research into the espionage affair led me to read Kisch’s 1920s play about Redl’s last day and then look at his other plays, none of which had come over into English. Among these works for the stage one stood out immediately. This was his comedic treatment of the story of a rowdy Prague prostitute (nicknamed ‘Toni Gallows’) who argues her way into heaven. I translated the two plays and began to build the present book around themes the plays address and the role this ‘theatrical’ phase of Kisch’s life played in his writing as he soon became ‘the raging reporter’ and the star of international reportage during the years between the two world wars. As the reader can see, these are diverse topics, but I have tried to tie them together in a sensible fashion. Remote from Kisch’s day and concerns, but culturally significant as a gloss on his work, is the present book’s examining the long afterlives of both of these stories in several media over the last century, a topic that informs my ideas of what happens when historical events become the basis of artistic transformations.

The preceding is the specific background of how my interest in Kisch and his writing evolved. This had a ‘prehistory’ of many years of reading Central European history and literature, supplemented by numerous trips to that part of the world, which led me to write essays about the region’s writers, history and culture that were published in small magazines, starting in 2011. For these earliest opportunities to publish I owe thanks to Dr. Ewa Thompson, editor of The Sarmatian Review, who accepted long pieces about Andrzej Stasiuk. Similar gratitude is due Zsófia Zachár, who opened the pages of the The Hungarian Quarterly to an essay about Hungary’s beloved Gyula Krudy. Regarding the Redl affair, my personal experience as a sergeant in the US army’s military intelligence branch during 1968–1969 whetted my curiosity about the once-famous espionage case. But, in order to write the present book, I had to expand my reading to include a large number of specialized historical works, critical writing about Kisch, and a variety of Central European novels in translation. I also needed directional guidance and practical help.

Over the years I received advice, encouragement, and assistance from numerous people who took an interest in my writing about Kisch in general or the Redl espionage affair and the ‘Toni Gallows’ play in particular. Here is where I thank them. My earliest advisor and supporter was the talented linguist, translator, and writer about Central European culture, the late Harold B. Segel. In the course of doing research about John Osborne’s Redl play I received similar support from Osborne’s biographer, Luc Gilleman, also sadly deceased before his time. I thank Charles Sabatos as well―he is the skilled translator of two novellas and one short story written by the inventive Pavel Vilikovský, and he was happy to correspond with me about Vilikovký’s writing. In discussing the complexities and unresolved details of the historical Redl case I received sound advice from Dr. Ian Armour, who has written about Central European history and military intelligence matters in the old Dual Monarchy. In acknowledging help with matters pertaining to the complicated Czech-German-Jewish nexus, I thank Dr. Gary Cohen for useful suggestions, and similarly, with respect to Weimar-era theater, Dr. William Grange. I owe a debt of gratitude to James Walker of Camden House, who read an early draft of the manuscript and gave me useful advice about rewriting and reorganization of the text. For their enthusiastic and encouraging responses to a late draft of the manuscript, which elevated my mood, I thank Dr. Leslie Morris of the University of Minnesota and Dr. Todd Herzog of the University of Cincinnati.

Researchers and staff members of several institutes in Germany, Austria, and the Czech Republic also assisted me by sending documents and downloads of old films and television plays that are often difficult to locate. Dr. Viera Glosiková, of Prague’s Charles University faculty, was invaluable, sending me her articles on Kisch as a dramatist and remarking on this part of his life. With regard to old plays, films, and contemporaneous critical reactions to them, I thank the following for bibliographical guidance and help in securing hard-to-get materials: Karolina Koštálóvá of the National Library of the Czech Republic; Matĕj