On the dancefloor, I heard someone say that the Most Important Artist in Mexico was there. That phrase, it seems, has the same atomic number as uranium. Some people went over to talk to him. Later, the Most Important Artist in Mexico took a young woman by the waist and they danced psychedelic cumbias. I thought he was a good dancer. Every so often, people interrupted his dancing to engage him in conversation. It’s a shame the woman who prefers the cracking to the nuts didn’t dance psychedelic cumbias with the Most Important Artist in Mexico. The dancefloor would have gone up in flames.

The secret of those people going over to interrupt the Most Important Artist in Mexico while he was dancing, now that I think about it, must lie in the very word ‘important’. In this city, we could form a cult around that word.

We left the party at the gallery and went to pick up a few things for dinner. I thought I saw Oscar Wilde in the supermarket. I once saw Fernando Pessoa choosing fruit at the Thursday market.

Today is Sunday. Jonás is at his friend Marcos’ house right now. Here at home, it’s a Sunday for puzzles. What came to nothing first, the corny aunt or the corny poetry she liked to read?

A Sunday for making up pointless sayings.

All texts are grey in the dark.

Stories, like buildings and wars, begin with drafting.

Bookkeeper, keep to your books.

And you know what? A notebook can be a Milky Way of letters.

What does ideal mean? The ideal weight. The ideal height. The ideal house, salary, job. The ideal book. The ideal person. To me, the bell they ring when the rubbish truck is coming is ideal: no accident, no disaster, no catastrophe has the good manners to announce its arrival like that.

I’m swimming diagonally, look. It’s getting late, why aren’t you back from Marcos’ house? I’m not going to ask you the Proust questionnaire; I think the Beckett questionnaire would be better. Come and see.

1 Right leg or left leg?

2 Company or solitude?

3 How would you translate the word lessness into Spanish?

4 How many times do you suck on a stone before putting it in your pocket?

5 A dark room, a voice speaks to you. What does it say?

6 Your loved ones live in dustbins and you have a single chocolate-chip cookie. How do you share it?

7 A king with a supermarket trolley or a tramp with a cardboard Burger King crown?

8 What do we talk about when we talk about Godot?

One way of turning into a swallow is by writing: I’m a swallow. But can the written word break the silence like a song?

Oh, music. I like music so much. But not the birds’ kind. I like music I can sing in the kitchen while I’m cooking, or in the street while I’m walking along. I know what song you have in your head, Jonás. Sing it to me. You’re a good singer, come on.

What genre, what kind of music do we like? It’s hard to say, if Ovid is the first punk and Ramones tracks are classics. And they are, aren’t they, now the internet is our Alexandria and we’re all Aristophanes of Byzantium?

Music. It’s so good. If I had to pick ten songs out of all the music I know, I’d pick one by Bob Marley and one by Bach. The two of them would sit together on the same list, with the same panache. The songs that are furthest apart would be like strangers who hit it off right away.

Jonás plays the piano really well. He has beautiful hands, long fingers. He’s no good at working music out by ear. Most of the time, he plays from memory, but when he forgets something he looks over the sheet music on the piano at his parents’ house. His repertoire is what’s contained in those seven or ten notebooks with missing pages: his father’s favourite pieces. Jonás plays Bach’s preludes and fugues wonderfully. If I tried to play Bach on the piano, the part I’d do best would be grunting like Glenn Gould.

The other night, while his sister and I were making quesadillas, Jonás tried to work out ‘Wild is the Wind’ on the piano. It was a disaster.

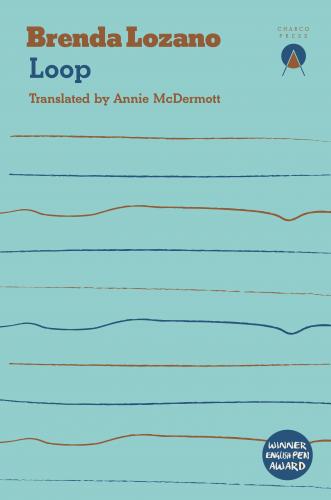

What do I do? What’s my job? Aside from working in an office, how do I spend my time? I spend my time drawing all sorts of lines. This Sunday I drew a lot of lines like this one:

____________________________________________

I drew lines with a blue pencil. Navy-blue lines, about as many as there are ruled on each page. I drew them with my eyes open and with my eyes closed. With my right hand and my left. Now I’m closing my eyes as I write this line. Like letting go of the steering wheel, look how I’m veering off course. Still, you need a notebook if you want to experience all the different kinds of lines a person can draw.

I drew the lines with a blue school pencil. I’ve realised that lines repeated from the top to the bottom of the page look like waves. To quote the sea:

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

‘The sea is the purest and foulest water: for fish drinkable and life-sustaining; for men undrinkable and deadly’, I read in a book by Simone Weil. In other words, the stairs that go up and the stairs that go down are one and the same.

It’s true, I’m in the middle of the sea. I thought I was swimming forwards, but I’m getting further away. What a strange sensation, thinking you’re getting closer when really you’re getting further away. Maybe I should ask Tania’s cousin for more detail, or enquire on the strip in Acapulco.

There are three thick lines in this Ideal notebook: the sea, the dwarf and the swallow. They’re three siblings talking about Jonás. My Jonás. The sea is the oldest, the dwarf is in the middle, and the swallow is the youngest, my favourite. The sea has always been jealous of his sister, the swallow. When they were children, he tried to give her away to the rag-and-bone man.

The rag-and-bone man must have had a Greek equivalent. In some corner of Greek mythology, the original rag-and-bone man drew things towards his cart with the power of his mind.

My Ideal notebook can be an iPod.

An ideal notebook is also a karaoke booth. In its infancy, an ideal notebook can be a drinks coaster, and in later years it can be used to wedge doors open. An ideal notebook of reproductive age opens its two pages even if it’s late, it opens its pages even if it’s a Sunday morning, like now. An ideal notebook is also a telephone. An ideal notebook allows a Greek metamorphosis to take place in the middle of an office like the one where I work. An ideal notebook isn’t written in the third person, or in the first or second, it’s written in all three because it’s ideal. The same goes for the verb tenses. An ideal notebook can be short, fragmentary, disconnected, long and in-depth, or superficial. It does everything, it allows everything, because Hermes is the almighty father of notebooks.

An ideal notebook has special effects, listen:

A building collapses.

A city crumbles.

The sea parts in two.

A storm breaks.

An ideal notebook knows, above all, that it can’t be ideal because being ideal means always being just out of reach – and not right in front of you, Bic pen.

I searched for the Ideal notebook brand online,