If, however, multiple cars with identical traits (such as hundreds of kindred Mustangs, all destined for Shelby American) were ordered, that DSO contained multiple cars. Shelby submitted DSOs for cars to be built to a very specific configuration. These were processed and filled by Ford, just as for any Ford dealer in any district across the United States.

Shelby Mustangs were like no other muscle or performance car of the period. That’s not a subjective evaluation based on the cars’ relative “coolness” (or perhaps, in terms of performance, “hotness”). It’s an objective assessment based on the car’s unique construction method, designed from the beginning with very specific features for the conversion from production sporty cars for the many to specialty sports cars for the few.

The GT350 also contributed to another almost revolutionary aspect of the Mustang. Just as the Model T defined an entirely new class of automobile (affordable, basic transportation for everyone), the Mustang was the first of a new category of car. Before long, cars including Chevrolet’s Camaro, Plymouth’s re-designed Barracuda, and Pontiac’s Firebird (pony cars all) were developed in response to the new market created by Ford’s Mustang.

Although the Ford Mustang defined a new class of automobile, in Shelby form, it also redefined the muscle car. Prior to the arrival of the GT350, muscle cars were large cars, such as the Chevrolet Impala and Pontiac GTO, powered by large engines. The Mustang GT350 took a pony car and gave it true performance potential; it made the pony car Mustang a contender in the muscle car arena. The two different classes of automobile, the pony car and the muscle car, converged in one package. From that point on, muscle cars were never the same again.

Whether production occurred in Southern California or Michigan, prior to each year’s production, Ford determined the configuration of the platform Mustangs to be shipped to Shelby. Receiving those Mustangs in multiple DSOs, or batches, allowed for subtle “tweaks” to be incorporated into each successive group of cars and also relieved Shelby from having to purchase and find storage space for an entire year’s worth of Mustangs at one time. Mustangs destined for GT350/GT500 conversion were so annotated on their individual build sheets. (Photo Courtesy Jack Redeker)

EVOLUTION (INTO LESS REVOLUTIONARY)

Although the ’65 Mustang GT350’s performance was by no means understated, the car’s appearance was. It really didn’t look like anything other than just a plain Mustang with stripes. Performance enthusiasts happily overlooked the visual shortcomings, but the car needed greater visual impact if it were to appeal to a wider audience.

For the tiny microcosm of true performance car enthusiasts, the January 1965 arrival of the Mustang GT350 from Shelby American was as big a deal as the debut of the Ford Mustang to the American automotive universe. Contemporary automobile magazines were enthralled with the GT350 and sang its praises. They described it as “one of the most exciting cars to hit the enthusiast’s market in a long time” and “a car that positively exudes character.”

Unquestionably, the GT350 offered the enthusiast (the car owner who deliberately sought the most convoluted path from Point A to Point B) an enjoyable experience behind the wheel. But there was also the understanding that the pleasure was not without cost. It was a part of a give-and-take package deal. In exchange for the car’s performance, the enthusiast (happily) paid with heavy steering, a stiff clutch, even stiffer brakes, a bone-jarring ride, and side-exiting exhausts that sounded (to the car’s occupants) as though they were routed directly into their ears. The automotive magazines sang the praises of the GT350 and described the machine as “a brute of a car.”

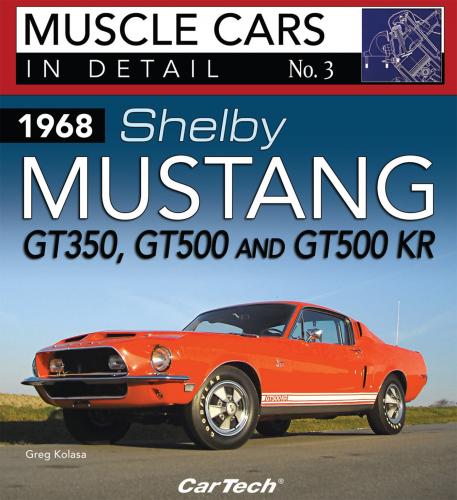

Also at issue was the car’s appearance. When it was designed, the GT350 was deliberately created with an understated appearance, differing only minimally from the Mustang on which it was based. But despite the car’s considerable capabilities (which had to be experienced to be believed), it appeared to be little more than a slightly made-over Mustang. Sales of the first Shelby Mustang suggested that there were more car buyers for whom it was important that the world know that they were driving what looked like a hot car than there were those who didn’t care. Even Shelby American recognized the shortcomings of the GT350’s Mustang-like appearance, acknowledging that it could have sold more if the car looked less like the Mustang.

SELLING OUT MEANS SELLING MORE

As Shelby American sat down to plan the second-year GT350, it recognized that the car would have to evolve to survive. “Evolve” actually meant incorporating characteristics that may have been distasteful to Carroll Shelby and the Southern California hot rodders who built the first GT350: refined, soft, and even luxurious. But distasteful or not, it was the first step on an evolutionary journey necessary to ensure the continued survival of the model. They accepted that compromises had to be made in two significant aspects of the GT350: appearance and the rough character that defined the first GT350.

More visual separation from the base Mustang was needed. Shelby accomplished this through the addition of what may well be the two best-known features of any year of the Shelby Mustang: quarter windows and side air scoops. Those design cues, which are iconic today, provided the Shelby with an identity that was much more visually separated from the Mustang. It was still too easy, however, to characterize the Shelby GT350 as “just a Mustang with stripes” because the two still shared much body sheet metal.

Ford and Shelby made a few more additions to the GT350 that were intended to make the Shelby product more appealing to a larger client base. These included the availability of colors other than white, a rear seat, and an automatic transmission. A conscious effort was made to lower the cost of the car. Some subtractions were made that enthusiasts would likely miss but that the general driving populace would not. These deletions included the Koni shock absorbers, lowered front upper A-arms, and pricey (and noisy) Detroit Locker differential, which were either shifted to the “added cost” column of the window sticker or deleted entirely. The side-exiting low-restriction exhausts also went.

All of these revisions, although perhaps not palatable to true performance enthusiasts, nevertheless had a favorable effect on the car’s economics. With the same powerplant and underpinnings as the first-year GT350, the 1966 edition still had the flavor of its brash forefather. However, the car was clearly pursuing a path to a softer (and therefore larger) group of enthusiasts. Although it was certainly not to the true performance enthusiasts’ taste (and perhaps not even to the manufacturer’s), it clearly was appealing to the masses (and to Ford’s bottom line); softer was better.

Shelby American recognized that, for 1966, its GT350 needed more, not in the performance area, but in the “looks different from a Mustang” area. One of the solutions was a pair of features that have come to be described over the years as “iconic”: side scoops and quarter windows. Not only did they differentiate the GT350 from the Mustang, they channeled air to the rear brakes and provided better visibility for the driver. With the GT350 now available with a rear seat (another move to widen the car’s appeal), back seaters also enjoyed a better view.