I began to read more widely in this area, including, amongst many other writings, the work of the top contemporary Egyptologist Eric Hornung. Most of today’s Egyptologists are chiefly concerned with archaeological discoveries and specific artifacts, but Hornung has made a study of the more esoteric, religious aspects of his field. For example, in The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West, he wrote: “Early Christianity was deeply indebted to ancient Egypt . . . There was a smooth transition from the image of the nursing Isis, Isis lactans, to that of Maria lactans. The miraculous birth of Jesus could be viewed as analogous to that of Horus . . .” I also discovered that the scholar Karl W. Luckert at the University of Chicago had written a book in 1991 about the huge debt that Christianity owes to Egyptian sources. It was called Egyptian Light and Hebrew Fire. One of many well-known authorities in the area of mythology, Joseph Campbell, said in his highly popular PBS TV series of interviews with Bill Moyers, “When you stand before the cathedral of Chartres, you will see over one of the portals of the western front an image of the Madonna as the throne upon which the child Jesus blesses the world as its Emperor. That is precisely the image [Isis and Horus] that has come down to us from most ancient Egypt. The early Fathers and the early artists took over these images intentionally.” In similar fashion, I noted that in his classic book Man and His Symbols, Carl Jung, the renowned psychiatrist and expert on mythology, said, “The Christian era itself owes its name and significance to the antique mystery of the god-man, which has its roots in the archetypal Osiris–Horus myth.”

The process of digesting all of this previously unknown material is given some space in chapter 1 of The Pagan Christ. I wrote there: “What if it is true? The implications were enormous. It meant . . . that much of the thinking of much of the civilized West has been based upon a ‘history’ that never occurred, and that the Christian Church had been founded on a set of miracles that were never performed literally . . . And that has made all the difference, a huge and immensely positive difference for my understanding of my faith and my own spiritual life. Simultaneously, it has transformed my view of the future of Christianity into one of hope.” Many things came together in a synchronism of influences, ripening ideas and insights that together gave me the courage and conviction necessary to write The Pagan Christ, to promote it through the media, and then to defend it against what I correctly foresaw would be a very formidable storm of criticism.

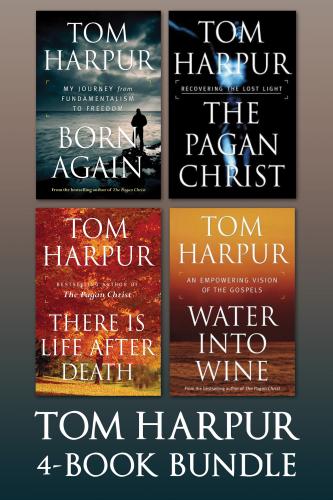

Looking back at the 2004 publication of The Pagan Christ, followed in 2007 by its sequel, Water into Wine, I have a deep awareness now of how perfectly it flows from all that had gone before. One has only to look at the earlier books and columns to see how the realization was already there that the only way forward for any rationally based religion of the future was that of a cosmic-oriented faith. The realization that the old creeds were now defunct and that they presented rigid, irrelevant obstacles rather than means to wider understanding was there almost from the very beginning. So too was the birth (for me) of the perception that the Jesus Story was not only a very old story but an archetypal drama of the Self in every one of us. In fact, chapter 14 in Life After Death (which offended some theologians at the time) was actually titled “The Christ Myth as the Ultimate Myth of the Self.” It was written in 1990, fourteen years before The Pagan Christ.

The part of The Pagan Christ that was the most striking and that stood the most apart from anything that had come before—also the part that I laboured over the hardest and that the media naturally exploited—was the chapter called “Was There a Jesus of History?” Other scholars as early as a hundred years ago had questioned the historicity of Jesus—and definitely the number of those doing so is growing today—but nobody mentioned them in divinity schools and certainly never from the pulpit. Indeed, if Christianity has been marked by any one single development beyond others in the past 150 years, it has been a paradoxical trend in North America particularly: on the one hand, an ever greater idolizing of a literal Jesus, who has usurped the place of God; and on the other hand, the work of critical scholars who have been busy removing the credibility of almost everything the historical Jesus is alleged to have said and done. The California-based Jesus Seminar’s twofold research projects—one into the words of Jesus, the other into his “acts”—eventually resulted in two books which between them said that less than 20 percent of either category had any claim to authenticity. Had the scores of participating scholars been less tightly connected with various Christian denominational schools and seminaries, there is no doubt in my mind that this figure would have been much smaller still.

The truth is that when my research for The Pagan Christ first began, the last thing on my mind was the possibility that it would lead where eventually it did on this issue. Once I realized that it might, I redoubled my efforts to get at the truth at all costs. Using all that I had learned at the feet of Professor Peter Brunt, my old tutor in Greek and Roman history, I checked and rechecked the very few lines of testimony that come to us from the second century CE. There is no secular evidence whatsoever for Jesus from the first century unless one ignores the fact that what Josephus, a Jewish historian who lived and wrote at that time, seems to say has been judged from earliest times to have been an egregious forgery. As pointed out in The Pagan Christ, the Jesus Story itself has a history. Indeed, it is woven into the very fabric of Western culture, its art, music and literature. It has been repeated and read literally so many myriads of times that it is the supreme meme of all time. The virtually total absence of any truly reliable hard historical evidence for the story has seldom been noticed because that’s the very essence of a meme; it is simply a unit of information repeated and repeated over and over again without question, indeed without the beginning of any thought of a question. While I don’t agree with the position of atheist Richard Dawkins, he is certainly right about this phenomenon in our culture, as outlined in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene. One of the most interesting aspects of the response to The Pagan Christ (which is continuing as I write) is that to date none of the critics who unanimously affirm Jesus’s historicity has come up with a single bit of solid evidence to support their position. Yet clearly theirs is the burden of proof. It rests upon their shoulders to establish their case. They have not done so.

What is truly significant, considering the important ramifications of this vital question, is that in the United States, in the fall of 2009, it was announced by the Scientific Committee for the Examination of Religion that the Jesus Project has been established. Noting that previous inquiries—most recently the Jesus Seminar—had not directly addressed the central issue of the historicity of Jesus and also that such undertakings in the past have always been largely directed by those with some professional ties to churches and various hierarchies, the founders of the project stated that they planned to bring together some fifty scholars from different but closely related fields over a five-year period. They have promised that the research will be done with no a priori assumptions one way or another. The total commitment is to objectivity and truth. The prevailing standards for all peer-reviewed historical investigation will be scrupulously followed and upheld. The simple question will be: “Did Jesus exist?”

While obviously it is too early to guess what the project’s findings will be, the fact that, after nearly two thousand years, such an endeavour is deemed by a scholarly body to be reasonable, academically legitimate and of some urgency says a very great deal. Clearly the matter is anything but the firm, settled and obvious “gospel truth” that a popular majority would have it believed to be.

To tell the full story of the response to The Pagan Christ would take a book of its own. There has been an incredible outpouring of letters to this day witnessing to the joy and sense of relief experienced