Mithraism is in fact a primordial form of sun worship whose Roman version ultimately worshipped Sol Invictus, “the Unconquerable Sun.” Mithras was believed to have “slain the bull of heaven”—perhaps a reference to the timing of his appearance with the close of the zodiacal age of Taurus. There are several hundred monuments or ruins connected with Mithraism in and under Rome, including more than one Mithraeum, or cultic shrine. These were built over a cave or hole in the rocks. In other words, the saving light was thought of as having been “born” in the womb of a cave. Mithras was believed to have had a virgin birth and twelve followers or disciples. He was viewed as a saviour figure who died and rose again from the dead; his birthday was December 25; he performed miracles of healing, laid down a high standard of personal morality and was called, among other things, the Light of the World. Mithraism had its sacred meal of bread, water and wine, and these elements were consecrated by priests who were called Fathers.

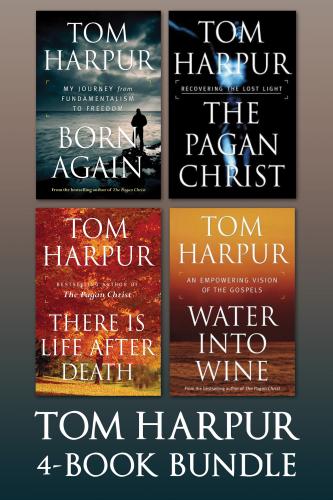

In the light of all of this, it is not surprising that the great African Church Father Tertullian (c.160–c.220 CE) was so disturbed by the similarities that he tried to explain them away by the highly unconvincing dodge of saying that the devil had inspired them to parody the Christian counterparts or “originals.” In any case, I knew that Mithraism had had considerable appeal for soldiers in Rome’s armies and that its monuments could still be found today in abundance all along Rome’s ancient and far-flung frontiers. The time I spent in first-hand examination of some of these remains while awaiting the funeral of Paul VI played an important part in my research over a decade later for what became The Pagan Christ. The influence of Mithraism and the other Mystery Religions upon earliest Christianity cannot be denied.

Rome, which is always thronged with eager tourists in the summer months, was filling up even more with every passing day. Meanwhile, the blazing heat of August baked the streets and squares relentlessly. In St. Peter’s, where the body of the pontiff was beginning to emit an increasingly distinct odour, making it plain that the limited embalming and the hidden ice beneath the flowers were no longer adequate to the task, large fans were installed and the crowds filing past were kept at a greater distance than earlier. There were still three days to go before the funeral itself. The 116 cardinals who were eligible to vote in the upcoming conclave (after the death of a Pope a conclave to elect his successor must be held not fewer than fifteen days or more than twenty days following) were already flying in from around the world, and speculation about the likeliest candidate was the sole topic of lively journalistic debate over the wine and pasta in the trattorias flourishing in the streets surrounding the Vatican. Rumours of all kinds were flying, but the consensus was that the next Pope would be Italian as well, given the more than four hundred years of tradition—the last non-Italian to be elected Pope was Adrian, a Dutchman—and the fact that with a total of thirty-three candidates the Italians were by far the largest single bloc.

In his will Paul VI had made it plain that he wanted his funeral to be “pious and simple,” with no elaborate catafalque—a raised platform to facilitate public viewing to the end—or other special frills. So the man in charge, Cardinal Villot, the Secretary of State, did his best. Nevertheless, the decision was made to have the funeral Mass outdoors in the Piazza di San Pietro itself. On the day, the TV cameras rolled and the Vatican choirs, the scarlet-robed cardinals and the hundreds of white-surpliced priests, against the magnificent backdrop of Bernini’s great colonnades and the Basilica of St. Peter, accompanied by some of the most sublime music on earth, combined to make the day indelibly memorable. The following day I left for Toronto and a brief return to the Star before preparing to come back again for the papal election two weeks later.

By the time I arrived back in Rome, August was all but over and the city was recovering slowly from the “tourist shock” of midsummer. I was able to book into my favourite hotel, the De La Ville, on the Via Sistina close to the top of the Spanish Steps and not far from the Villa Borghese, with its classical artifacts including sculptures by Bernini and Michelangelo. The roughly half-hour walk from there down the steps to the Piazza d’Espagna, along the Corso to the Piazza del Popolo, across the Tiber and along its bank past Castel St. Angelo to the Vatican press office just off St. Peter’s Square was one of the joys of being in the Eternal City.

The assembled cardinals met briefly on the evening of August 24 to prepare for the conclave, and the first session in the Sistine Chapel was held on the following morning. A Vatican press officer pointed out the quaint, somewhat frail-looking metal chimney now sticking out from the roof of the chapel and told the large crowd of reporters crushing around him in the piazza that after each ballot it would emit black smoke if there was no clear winner and white in the event of an election. The tension around St. Peter’s was palpable as banks of TV cameras were mounted and uptight journalists stood around in buzzing knots on every side swapping rumours and floating theories about a liberal–conservative split among the cardinals. The first ballot was cast before noon the next day. The first wisps of smoke that emerged were a pale grey, causing some confusion. However, it soon changed to black and everybody relaxed. In the afternoon there was a similar flurry of excitement but with the same result.

On the Saturday morning, a very hot and sunny day, I met Ken Briggs, religion editor of the New York Times and a former Methodist minister, and we had coffee at a sidewalk table on the Via Conciliazione, just outside the Piazza di San Pietro. Our location afforded an unobstructed view of the roof of the Sistine Chapel. Our work had thrown us together a number of times in unusual places around the world, and there was a lot to discuss and learn from one another. Eventually there were some puffs of black smoke again; the third ballot was over. We agreed to meet at the same spot later that day.

It was a sleepy, simmering kind of afternoon, and we were again at the sidewalk café enjoying a cold drink while speculating that nothing would now likely happen until Monday when suddenly a plume of white smoke billowed up and everybody began running around and shouting at one another. A Pope had been elected on the fourth ballot! Almost miraculously the word spread and thousands of excited people began streaming through the colonnades and streets into the square. By the time the official announcement “Habemus Papam”—“We have a new Pope”—was made from the loggia above the entrance to St. Peter’s, the piazza was filled to overflowing. The sense of anticipation as we awaited the name of the new pontiff was a unique experience for nearly everyone there. Then it came: Albino Luciani, the Patriarch and Cardinal of Venice—a man not on anyone’s list of likely contenders—was the surprising choice. The crowd, chiefly Italians though heavily laced with representatives of virtually every country, roared its approval as the man who would shortly be known far and wide as Il Papa di Sorrismo, “the Smiling Pope,” was introduced and waved his greeting to a sea of upturned faces.

I have seldom worked harder in my life than I did for the rest of that Saturday and well into the early hours of Sunday, reading up on Luciani, writing and rewriting the story of who he was and how surprised everyone was at his being chosen. He was the total opposite of Paul VI and in every way a breath of fresh air for Christians of all backgrounds everywhere. What made it doubly difficult was that my right arm had become sore and inflamed during the day, and it was soon clear as I typed away that an infection of some kind was making the elbow red and badly swollen. When he saw me the next day, Briggs thought it was clear I was running a fever and he persuaded me to go to a small clinic near the Colosseum run by some Irish Catholic nuns. I stayed there for two days receiving wonderful care, minor surgery and an eventual clean bill of health. The important thing was that the account of the election was filed in time and ran on the front page at home that Sunday.

With regard to Luciani, I was startled from the outset at how much this man resembled my own father, especially when the latter was showing his kindliest, most winsome side. Their backgrounds could not possibly have been more different, but I truly liked Papa Luciani from the start. Perhaps what was most appealing about the man was his complete lack of any pretence or side. He was open, unassuming and apparently bent upon a fully reformist approach to the papacy. Luciani had already scandalized some Church authorities