1

SURPRISED

BY GOD

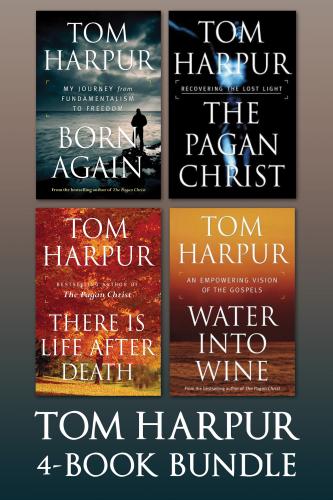

MANY READERS of this book will be aware that in the spring of 2004, just before Easter and within days of my seventy-fifth birthday, my world was rocked by the publication of The Pagan Christ. I was thrown suddenly into the centre of a whirling vortex of controversy, praise, criticism and media attention such as I had never experienced before. Already a bestseller even before its official “pub date,” the book remained at the top of several Canadian bestseller lists for many months, and the Toronto Star and the Globe and Mail later judged it to be the number-one bestseller of the year. The book and its author were attacked with vitriol by conservative critics in all camps, while emails of gratitude and congratulation began to flow in by the hundreds from an ever-widening circle of avid readers whose primary emotions seemed those of joy at release from old, religion-induced fears and of renewed spiritual energy at now being freed to get on with a rational trust in God. My publisher and chief editor, forty-year publishing veteran Patrick Crean at Thomas Allen Publishers, said publicly that The Pagan Christ “is the most radical and important book I have ever worked on.” We could scarcely keep up with media requests for interviews, while simultaneously several TV producers were vying for the film rights. Eventually, CBC and an independent producer, David Brady Productions, won out. There was also a behind-the-scenes tug-of-war for foreign rights. The book went on to sell in the United States, Australia and New Zealand, and in translation in France, Holland, Germany, Japan and Brazil.

Put in its simplest form, the message of The Pagan Christ is that the Christian story, taken literally as it has been for centuries, is a misunderstanding of astounding proportions. Sublime myth has been wrongly understood as history, and centuries of book burnings, persecutions and other horrors too great to be numbered were the result. The light crying out to be rediscovered is that every human being born into the world has the seed or spark of the Divine within; it’s what we do with that reality that matters. Building upon the work of earlier scholars, I set out my reasons for being unable to accept the flimsy putative “evidence” for Jesus’s historicity. In its stead I made the case for the Isis–Osiris–Horus myth of ancient Egypt as the prototype of a much later Jewish version of the same narrative. The media jumped on that as their leading theme. The message of my follow-up book Water into Wine leads on from there. Its thesis is that the “old old story” is indeed the oldest story in human history, and it focuses upon us. The story of the Christ is the story of every man, woman and child on the face of the earth. The miracles, rather than being snipped out of the text with scissors à la Thomas Jefferson (who did it to solve the problem of their otherwise seeming to contradict the very laws of physics said to be God’s own creation), are shown to be allegories of the power of the divine within us all. Read as historical, they border on the ludicrous. Read as allegory and metaphor, they shine with contemporary potency for one’s daily life.

Obviously, for a theologian who had become a freelance journalist with the express objective of reaching the greatest possible number of people with a genuine message of faith and hope in terms they could readily comprehend, it was an exciting, even thrilling moment in which to be alive. Everything before that took on the aura of a guided preparation for this peak adventure. But it was a very stressful time as well. I had challenged traditional religious doctrines and taboos in a wholly radical way and the guardians of orthodoxy were not about to take that without a fight. While there were many clergy of all denominations among the enthusiastic readers of The Pagan Christ, and subsequently of Water into Wine, there were also those who felt it their duty to attack these books vigorously in print, on TV, in the lecture hall or from the pulpit. A few former clerical friends disappeared into the woodwork altogether, while many admitted they had no intention of upsetting their beliefs by exposing themselves to “heresy.” In other words, they were afraid to have to rethink in any way what they have chosen always to preserve “as it was in the beginning, is now and evermore shall be, Amen.”

Looking back to even my earliest memories, I realize how deeply rooted was the impulse to search for and know God—and at the same time to possess a reasoned, reasonable faith open to everyone and not just to holy huddles of specially chosen ones. This is far from saying that I held reason alone to be the sole path to that ultimate mystery. As the familiar words of Blaise Pascal in his Pensées remind us, “The heart has its reasons which reason knows nothing of.” However, our greatest gift as human beings is our faculty of self-reflective consciousness (our ability to think about what it is we are thinking and feeling)—in other words, our ability to think rationally. What we hold to be true about God must never contradict or oppose reason. Thus, for example, while I believe the current mushrooming crop of atheists, however vocal or eloquent they may be, to be very mistaken, I have a great deal of sympathy for their sense of exasperation or even disgust at much of the pious, popular religion of our time that has little use for reason at all.

This morning I received a letter from a young New Zealand woman who has just written her first novel. Speaking of The Pagan Christ and Water into Wine in particular, she wrote: “Your work gave me the courage to journey where I felt my soul had always been.” Interestingly, that has been the overwhelming message carried by the response to both volumes. I say this with the greatest sense of humility because of my commitment to the belief that the Holy Spirit of God does indeed guide and inspire us all the days of our lives no matter how often we stumble or fall. Indeed, one of the things I believe the discerning reader will find in the narrative that follows here—and may well recognize from a similar phenomenon in his or her own life—is that events or insights which initially seem isolated and perhaps unconnected to anything else often can suddenly become pregnant with meaning, linked together, illumining a far larger landscape than was anticipated at first.

Reflection since the momentous happenings of Easter 2004 and then Easter 2007, when Water into Wine first appeared, has shown me very dramatically that neither of these books dropped from the sky. As what follows illustrates, they came as the product of many years of study, travel and experiences of many kinds. Yes, there was much immediate, painstaking research in the laborious months before publication, but all the major themes were already there, percolating throughout the length of an eventful life. My editors encouraged me to digest the research but above all to use my own “voice” in the light of a lifetime of experience, and that is eventually what happened. I had finally found a way to make sense of the traditional Christianity in which I had been reared and professionally trained and to which I owed so much in a way that resonated with my heart as well as my intellect.

To my mind, the process I’m describing is somewhat like that of the prospector of an earlier era who spent his entire lifetime searching for an elusive treasure. There were moments when his journey up winding creek beds and over mountain trails seemed bleak and void of purpose. But from time to time he would catch amidst all the debris and seeming chaos around him a tiny gleam of gold, the promise that the reality was there somewhere to be found. Then one day, perhaps when and where he least expected it, the true mother-lode was revealed to him and he rushed to share the good news. Using this as an analogy, I now see that the creation of The Pagan Christ and Water into Wine was a kind of spiritual alchemy. The dross of weary-making traditionalism and the emptiness of outworn and in some cases enslaving dogmas had in spite of themselves been carriers of a buried wisdom. There truly was some spiritual gold to be found buried and hidden in “them there tired ecclesiastical hills.”

When I was preparing for my final examinations in Classics at Oxford, my tutor in philosophy, Richard Robinson, called me to his study for a brief chat. He was a man who made a habit of taking long pauses for thought before he ever spoke a word. At times it was almost alarming, as if he’d forgotten what he was going to say. But he definitely had not. It’s a habit many of us could well emulate, to everyone’s profit! On this somewhat solemn occasion he said to me: “Harpur, let me give you a word of advice. When you get the examination paper, study it well for a few moments. If you see a question you can write something intelligent about, do so. If you don’t see such a question, then pick out a question that is itself questionable. Examiners are not infallible. They can be wrong. In any case, you have nothing to lose by taking the