“Oh, Zephie,” she squealed, “come down here! Come down right this second!”

“Cherry,” he said, pulling himself onto a higher branch.

Sophie clambered after him, but he just giggled. He thought it was a game, so he climbed even higher to where the branches were thinner and bent under his weight.

“No, Zephie! Stop! Don’t go any higher. You’re going to fall and break your neck!”

Then she heard Maman from the back porch. “Sophie! Zephram! Where are you? Oh, no! Not up in the tree! Hold on tight, mes enfants! Don’t fall! You’ll break your necks!”

She ran under the tree branches and held out her skirt as if to catch them if they fell. Sophie stared down at her mother, then back up at Zephram. She knew she had to get to him before he crawled any farther. The branch was so thin that it could snap under his weight at any moment.

Suddenly he seemed to realize the danger. “Fall?” he said, his voice quavering, his eyes huge.

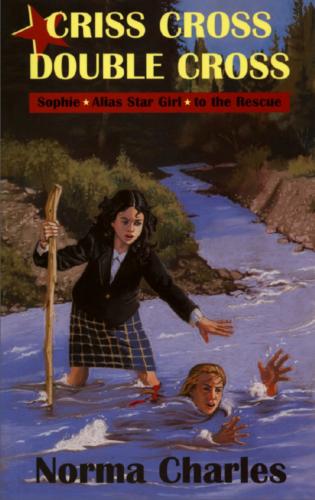

“Come on, Star Girl,” Sophie muttered to herself as she cautiously eased herself up to where she could reach him. “Hold on tight, Zephie! I’m coming to get you.” She clutched a branch with one hand and leaned way over. “Got you!” she said, grabbing the back of his romper with her free hand.

“Hold on there!” Maman cried. “I’ll get the ladder.”

As her mother raced across the backyard to the chicken pen, Sophie held her brother’s romper in such a tight grasp that her hand throbbed, but she didn’t dare let go.

He stared down at her, his eyes filling with tears. “Fall,” he whimpered. “Fall down.”

“No, you won’t fall, Zephie. I’ve got you really tight.” But she wasn’t sure how long she could hold on to him. Or hold herself on to the tree, for that matter. She didn’t dare look down. She stared straight ahead at the fluttering green leaves.

Maman dragged the ladder across the yard and frantically set it up under the tree, leaning it against the branch just below Zephram’s legs. She gingerly climbed the ladder and reached into the branches for her little boy. “Pass him down to me, Sophie.”

Before Sophie could pull her brother loose, he leaped at his mother, squealing, “Maman, Maman!”

“Oof!” Maman grunted as he descended upon her. The ladder lurched and swayed. For a second Sophie thought it was going to topple, but Maman managed to grasp a branch to steady herself. “There now. There now, mon petit.” She took a deep breath and shifted Zephram under her arm, holding him like a football. “We’ll just go back down the ladder.” When she stepped onto the grass, she put Zephram down and gave a great sigh of relief, wiping her face, shiny with perspiration.

Sophie swung out of the tree like Star Girl and landed at her mother’s feet.

Maman shook her head, her hands on her hips as she looked at Sophie. “I don’t know where my children get it. You two must be part monkey. Always climbing, climbing...”

“Sorry, Maman. I was watching Zephram every minute. Really I was. I don’t know how he got up that tree so fast.”

Raising her eyebrows, Maman gave Sophie a cross look. Then she carried Zephram inside the house for his afternoon nap. Sophie trailed behind her.

After Zephram was safe in bed, Maman went back into the living room to continue practising the piano. “Monsieur le Curé said that the regular organist will be away on Sunday, so he asked me to play at High Mass,” she said. “The music has to be perfect.”

Sophie took a pile of her Star Girl comics out to the shady front steps to read. She’d write a letter to Marcie later. It was much too hot to do it now, even in the shade. She raked her fingers through her curly hair and wiped the sweat from the back of her neck. She thought about how lucky her brothers were, diving and swimming in the beautiful cool, clear water at Deer Lake.

She opened her favourite Star Girl comic. It was the one where Star Girl saves a train loaded with vacationers from crashing over a cliff by flagging down the engineer with her star-studded cape in the nick of time. That was what she needed! A star-studded cape. Then she could rescue somebody, too.

A boy appeared at the front gate. “Hey, Sophie, want to play?” It was her next-door neighbour, Jake. He had red hair and freckles like her brother, Henri.

“Sure thing,” Sophie said, dropping her comics on the top step. “I thought you were gone away on holidays.”

“We got back last night. We were on Vancouver Island looking for a new house in Port Alberni where my dad got a new job at the mill.”

Sophie’s stomach lurched. “You’re moving away from Maillardville?”

“Not until the end of the summer.”

That was a couple of weeks away, so Sophie wouldn’t have to worry yet about losing her friend. “So what do you want to do?”

“Want to play marbles?”

“I forget where I put mine. How about hopscotch? You can go first.”

“Sure.”

They drew the hopscotch squares with sharp sticks in the dried dirt path in front of the hedge. Jake found a piece of white china for his marker, and Sophie found a grey speckled rock that was flat enough not to roll away when she threw it.

“Look,” she said, showing Jake. “This rock has a wishing ring.” A narrow white band went right around the whole rock.

“So make a wish, why don’t you?”

Sophie shut her eyes. Now that she didn’t have to wish for a friend to play with, she wished hard for her very own bicycle, one with balloon tires and shiny fenders. “Okay,” she said, opening her eyes. “Let’s play. You’re first, remember.”

Jake stood on one foot and hopped through the squares. Before he had finished his turn, Elizabeth Proctor rode up on her shiny new bicycle. Again! Four times in one day! It was as if she were haunting Sophie or something.

“Wow!” Jake squeaked. “Love your new bike!” His eyes shone as he stared at Elizabeth. Sophie’s stomach felt very tight. Jake was her friend, not Elizabeth’s.

“Thanks, Jake,” Elizabeth purred, batting her eyelashes at him. “Can I play with you?”

For a second Sophie thought Jake might go off and play with Elizabeth and she would have no friend to play with. She grabbed her stick and scratched a big, deep cross into the dirt beside their hopscotch squares.

“Criss cross, double cross,” Sophie chanted at Elizabeth. “Nobody else can play with us. If they do, we’ll take their shoe and beat them till they’re black and blue. Criss cross, double cross.”

She stuck her hands on her hips and glared at Elizabeth with her angry Star Girl stare.

“Humph!” Elizabeth sniffed, rubbing her nose with the back of her hand. “Who’d want to play with you two dimwits, anyway?” She flicked back her hair, got on her bike, and rode away, her nose even higher in the air than usual.

“Gosh,” Jake said. “She sure does look mad.”

“I don’t care,” Sophie said. “She’s nothing but a mean old snob.” But she didn’t feel very good about what she had done. She was the one who had been mean.

“Yeah,” Jake said, “but what a beaut of a bike!”

The following morning Sophie