As is apparent, this complexity made the Rifle very expensive to produce. This flaw was exasperated by the high cost of American labor. Worse yet, the Winchester factory had developed around the rise of the traditional lever-action repeater, which hardly required modern production technology: the competing Winchester 94 and Marlin 336 were much simpler to produce. Even the Savage 99 had significantly fewer and larger, easier-to-manufacturer parts and thus offered a much higher profit margin, which, after all, was and is the name of the game.

Perhaps the biggest reason for the cessation of production of the 88 was a matter of demand. Apparently the generation that had just witnessed the development of the jet plane and the atomic bomb was not ready for a truly advanced design but rather preferred the nostalgia of the classic lever-action Rifle. These, based on the traditional Browning-derived styling with external hammers and lesser degrees of technical sophistication, continue to sell well. For example, the Winchester Models 1892, 1895, and 1886 have been reintroduced; the Model 1894 lasted until 2006; and sales of the Marlin Model 336 continue unabated. The ultramodern Browning lever action Rifle and Savage 99, regrettably discontinued, sell somewhere in between. The Model 88 has nevertheless achieved a cult status amongst enthusiasts, which keeps interest in it at a high level. As with Parker shotguns and pre-Model 70 Winchester Rifles, the Model 88 is in constant demand by collectors and, hence, gun dealers.

Those who recognized the technical merits of the 88 back in the ‘50s and ‘60s and were smart enough to purchase one may have actually cheated time. Winchester produced a Rifle that was not only a half-century ahead of itself in technology but was also one of the all-time great lever-action Rifles.

Now the question is whether Winchester will ever reintroduce the Model 88. The answer, as we see, it is likely “no,” since the Winchester product line has been greatly scaled back and its parent company Browning still offers the competing Model 81 BLR. But then, why not have two good levers available from one company?

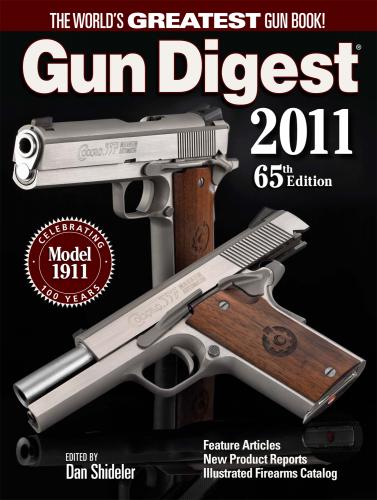

THE COLT 1911 The First Century

BY JOHN MALLOY

New names keep coming up for companies offering new 1911s. Legacy Sports now offers their Citadel 45 in full-size and compact versions.

Students of firearms are aware of the significance of the year 1911. In that year, a century ago, the Browning-designed Colt Model 1911 was adopted as the sidearm of the United States military forces. Perhaps no single semiautomatic handgun is better known, has had more influence on pistol design, or has had more influence on pistol design, than the 1911. Now, 100 years later, the Colt/Browning 1911 design lives on, little changed, and it remains amazingly popular.

Since its introduction, the 1911 proven itself as the United States military pistol in two World Wars and a number of other conflicts. Other countries produced the Colt/Browning design, made under license. Still other countries made unauthorized close copies of the pistol.

Civilian use of the big Colt pistol reinforced its value. By the midpoint of the 1900s, the 1911 was on its way to becoming one of the winningest target pistols use. In the latter part of the century, enforcement agencies were won over law enforcement agencies were won over to the semiautomatic pistol, and many went with the time-tested 1911.

For almost half its history, the 1911 reigned supreme as the premier semiautomatic pistol in America. During that time, no other big-bore pistol was even produced in quantity in this country. In latter part of the 20th century, other companies made competing semiautomatic pistols of more modern design, but the 1911 retained its popularity. With patent protection long gone, other firms began to make nearly exact copies-part-for-part-interchangeable 1911-type pistols-under their own names. New names, some now almost forgotten, entered the firearms lexicon. By the closing decade of the 1900s, other producers such as Springfield, Para-Ordnance and Kimber achieved major positions as 1911 manufacturers.

By the beginning of the 21st century, even companies that were making pistols with more modern features decided to get on the gravy train and began making their own 1911 pistols. Companies such as Smith & Wesson, SIG-Sauer and Taurus introduced 1911s.

The 1911 design, now a century old, seems to be at a peak of popularity.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

In the 1890s, the semiautomatic pistol was successfully introduced to the firearms world in Europe. In 1893, the Borchardt became the first commercially-successful autoloader, followed by designs of Mauser, Bergmann, Mannlicher and Luger. To these European developments was added one with an American name — Browning. John M. Browning’s 32-caliber pocket pistol was introduced in 1899 by Fabrique Nationale (FN) in Belgium. Early developments were relatively small in bore size, ranging from less than 30-caliber to an upper limit of 9mm. Around the turn of the 20th century, the concept of a larger-caliber semiautomatic pistol had been experimented with in several countries, including Great Britain. However, it took a design of American inventor John M. Browning to bring a truly successful big-bore pistol into being. Browning, along with his handgun work for FN, had provided designs to Colt. Colt saw promise in military sales and introduced a Browning-designed 38-caliber automatic in 1900. This caliber appeared to be a favorable one, as the US military was by then using 38-caliber revolvers.

However, the need for a largercaliber handgun became evident during the Spanish-American war of 1898 and the subsequent Philippine Insurrection. When the United States acquired the Philippine Islands from Spain as a result of the war, it was an unpleasant surprise to find that many Filipinos did not like American control any more than they had enjoyed Spanish rule.

The resulting insurrection was officially over in 1901, but deadly conflict, especially in the southern islands, continued well into the next decade. These southern islands were inhabited by fierce Moro tribes that had been converted to a form of Islam. The service sidearm of the time, the double-action .38 Long Colt revolver (marginal even in “civilized” warfare), proved to be inadequate to stop a charging Moro. Old Single Action Army 45-caliber revolvers were withdrawn from storage, had the barrels shortened to 5-1/2 inches, and were sent back into service. A quantity of 1878 double-action Colts, modified with a strange long trigger and enlarged guard, were also issued.

The stopping power of the old bigbore .45s proved to be far superior. However, they were stopgap measures. An effective standard modern handgun was needed.

What was needed? The famous Thompson-LaGarde tests, which involved shooting live stockyard cattle and human cadavers, provided one part of the answer: the new handgun would be a 45-caliber. Thus, the search for a new sidearm began in the early 1900s. Although semiautomatic pistols were coming into use, the cavalry still firmly favored the dependable revolver. The stage was set that any “automatic” considered must have reliability equal to that of the revolver and be a .45. A series of tests, to begin in 1906, was contemplated by the Army.

PRIOR TO THE TEST TRIALS

Two 45-caliber cartridges would be used: revolver use, and a rimless one for the automatic The rimless version was essentially similar

The rimless version was essentially similar to a commercial round produced by Winchester for Colt since the spring of 1905. The Winchester ammunition was made for Colt’s new 45-caliber autoloading pistol, which had been introduced in the fall of 1905.

The 1905 Colt .45, developed by John M. Browning, was a logical development of the locked-breech 38-caliber Colt/Browning pistol. The new .45 had a five-inch barrel, which gave it an overall length of about eight inches. It weighed about 33 ounces. Capacity of the magazine was seven rounds. The cartridge, in its original loading, pushed a 200-grain bullet at about 900 feet per second. It was a potent load for a semiautomatic pistol of the time.

To today’s shooters, the 1905 pistol might seem strange. It had no grip safety and no thumb safety. The shooter just cocked the hammer when he was ready to shoot. The hammer itself was of a rounded burr shape. The recessed magazine release was at the bottom of the