“Hazel,” said Jane Samuels. She’s the resident director of Penn House. In her perennial uniform of navy blue skirt and white blouse, she looks like a nun in street clothes. She was a nurse in Vietnam, and did jail time for pouring blood on the draft files in Catonsville.

I slipped into a seat at the long mahogany table, polished and gleaming despite stains from years of meetings. Marilyn Bartlett, head of tiny Hilleston Friends in Virginia, sat down beside me. Ted was already there, across the table.

“Good morning, friends,” said Jane. “A moment of silence.”

Ted bowed his head. He has thick, salt-and-pepper hair. I closed my eyes. It would be second period by now at school. How was Jacques managing?

Jane cleared her throat “So, it is my pleasure to welcome our keynote speaker. Dr. Bledsoe is on sabbatical from Oxford, teaching at George Washington University. Many of you are familiar with her research on cultural identity among children, so helpful as you include children of different nationalities in your student bodies. Please join me in welcoming her.”

Polite applause greeted the speaker as she stood and moved to the podium.

She was slender, wearing a simple, expensive linen suit. Eurasian—part Japanese, I thought.

“Thank you. I am delighted to address Quaker educators, for I have experienced the kindness of Friends. As Jane said, I study the development of national identity—with a special interest in trans-national children, children with feet in two cultures.” Her voice was low, the accent neither BBC nor Oxbridge. “My topic chose me, as is often the case. My mother was English, my father Japanese.” She adjusted fragile, gold-rimmed glasses with small, delicate fingers. “Complicating my own question of identity, I spent the first years of my childhood in Berlin, during the war, as my father was attached to the Japanese Embassy. In 1945, we were detained in the States at the Bedford Springs Hotel, in Pennsylvania. I was thirteen.”

It was like skidding onto unexpected black ice. I had known her, known her parents. Closing my eyes, I saw a small hand waving good-bye, flickering from the rear window as a black limousine drove away down the hotel’s driveway.

At the coffee break, I chatted with Marilyn and then retreated into the ladies lounge. The room was furnished with wicker and lined with age-spotted mirrors dating from when Penn House had still been a private home.

Dr. Bledsoe stepped into the room and slipped into a toilet stall. Twisting the faucet, I splashed cool water on my face and blotted it dry. She emerged and stood beside me, dusting her cheeks with powder. Our eyes met in the mirror. Hers were unchanged: almond-shaped, smoky gray-green.

“Cha-chan,” I said, “Charlotte—I’m Hazel. From the Springs.”

She froze.

Jane popped through the door. “Oh, here you are. Wonderful! Dr. Bledsoe, I wanted to be sure you met Hazel Shaw. Head of Clear Spring Friends—she’s developed a Peace Studies course. You two should talk.”

Charlotte Harada Bledsoe turned and smiled at Jane, perfectly poised. A diplomat like her father. A performer, like her mother. “Thank you. In fact, we’re old friends.”

“Really? What a small world it is! Find us at lunch, Hazel. You can catch up.”

But at lunch, I did not eat with Charlotte. She was besieged; everyone had questions.

“You knew her when you worked there?” Ted asked softly as we stood in line for chicken salad.

I nodded.

We ate with Marilyn, balancing plates on our laps, sitting in the narrow garden behind the townhouse.

“At my school, we haven’t ever had a foreign student. Unless you count the family that moved from New York,” said Marilyn.

“I get the occasional U.N. kid,” said Ted.

“How about you, Hazel? Diplomats’ kids?” asked Marilyn.

“They go to Sidwell,” I said. “We’re like Avis. We try harder. I have a Republican though. How’s that for cultural diversity?” Louisa Wilson, my Sweet Briar girl.

At the end of the afternoon, Jane sought me out. “Join us for dinner. Just Dr. Bledsoe and me. There’s a Japanese place near the Cathedral.”

The restaurant was small. The kimono-clad hostess exchanged a few words with Charlotte in Japanese, and seated us at one of the traditional low tables. The green tea hit my blood stream like elixir.

“Now how is it you two know each other?” asked Jane.

A pause. “Hazel worked at The Bedford Springs, where my family and I—stayed.” Polite euphemism, stayed. Diplomat’s daughter.

“Where is that, exactly?” Jane’s eyes sparkled with gentle curiosity.

“Bedford’s about half-way between here and Pittsburgh,” I said.

“I’m going there tomorrow,” said Charlotte. “To the Springs.”

“Could I come with you?” I asked, surprising myself.

“I would like that.”

Jane ordered sake. “A toast to your reunion,” she said.

We touched our porcelain sake cups together.

I drove the fifteen familiar miles back to campus. Turning between the brick bollards marking the school drive, I noticed our sign had been vandalized again. Clear Spring _ _ _ ends School, it read. A practical joke by one of my seniors, most likely.

I called Sally. “So, how was it today? Anything more from Louisa’s dad?”

“Not a peep,” she said. “Try and get some rest over the weekend.”

“Actually, I’m going away tomorrow. Just overnight. I met an old friend at the conference.”

Sally, my Quaker Angel, sees right through things with her bi-colored eyes. She may suspect, about me and Ted. Perhaps that’s why she didn’t press for any details about my plans.

“Good,” she said, “That’s good. Try not to worry. Way will open.”

“Could you tell Thomas the sign needs to be re-painted again? Wish we could figure out who’s doing this, bring him to P&D.” The Head, the Dean, two teachers, and two students sit on the Procedures and Discipline Committee. Louisa had been brought before us, after trying to hire another student to write a paper. The boy had totally misunderstood her request, she said. I just meant for him to proofread, check my spelling!

I started to pour my bourbon, but selected the unopened bottle of Suntory instead.

“I thought you didn’t like whiskey,” Ted had said when I bought it in Manhattan.

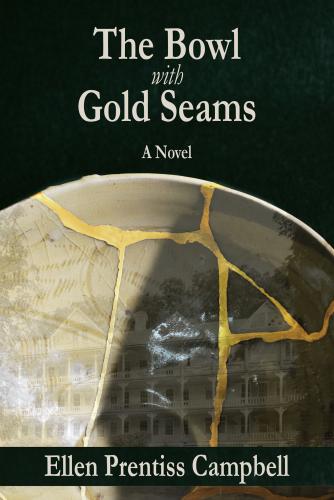

I retrieved something else from the very back of the cabinet, carried the small package to the table and unwrapped layers of tissue paper. The black pottery bowl had been broken and mended, the shards joined together with golden glue. The bowl’s design of blossoms and Japanese characters seemed caught in a net of shining gold seams. The long-ago artisan who fused the fragments with seams of lacquer dusted with powdered gold had transformed breakage into beauty, highlighting the damage as part of the bowl’s history rather than hiding its repair.

I used to display the bowl on the mantel beside my mother’s clock. One year, at my Head’s reception for entering students, a new parent said, “That bowl is a glorious specimen of kintsugi. Where ever did you get it?”

“A gift from a friend,” I said.

Afterward, I had it appraised at the Freer Gallery and learned kintsugi was born of a serendipitous accident in the fifteenth century. A shogun sent a broken tea bowl to China for repair. Dissatisfied with the way the mending’s visible staples