He pulled something from his waistcoat pocket. A flash of a sparkle glistened above his fingers as he held it out toward her. It was a ring, an engagement ring. The delicate filigree platinum setting held a large round-cut diamond encircled by smaller diamonds. It was stunning. She didn’t know what to say. The viscount laughed.

“You find this funny?”

He shook his head. “Funny, no. Amusing, yes.”

“Aren’t they the same thing?”

“No, indeed. This marriage arrangement is not ‘funny’ at all. I, too, had no choice in the matter. It was marry an heiress or give up everything. I, for one, have no intention of forfeiting my ancestral home, my title, or those lovely horses your father brought. So, unless you know a better way, we must abide by our families’ wishes.”

Stella didn’t know a better way. What would Daddy do if she disobeyed him? Would he disown her, deny her an inheritance? But there had to be a way out of this, didn’t there?

“As to your frankness, as you call it, it is most refreshing and, dare I say, amusing,” Lord Lyndhurst said. “I’ve been bored to distraction by English heiresses. Do you have anything else you wish to say?”

“No. I think I’ve said quite enough already.”

“Then follow me.”

After leaving the music room, he led her through the grand central hall, or grand saloon, as he called it, an expansive room with carpeted parquet floors, marble pillars, and a forty-foot-high fresco-painted vaulted ceiling that was more reminiscent of one in a cathedral than in a home. Stella resisted the urge to look up. The viscount stopped in front of one of several closed doors leading off the main hall.

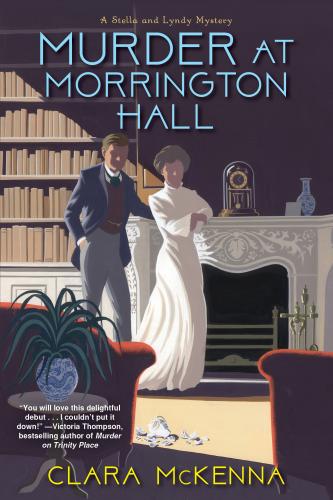

“This is the library.” He opened the door.

Stella, drawn in by the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, entered the room first. Her home in Kentucky had a library. The room had once been the log cabin Grandpa Kendrick built before Daddy had it incorporated into the bigger house. But as Daddy collected books, as he collected everything, exclusively buying the rare and most expensive ones, Stella hadn’t been encouraged as a child to peruse them. But she’d persisted in getting her hands on less expensive volumes, nagging first her mother, then her governesses, and then Aunt Rachel to satisfy her insatiable appetite, especially for adventure stories and romance novels. Daddy would respect the cost of such an extensive, and presumably priceless collection. Stella couldn’t wait to see what treasures it held.

“He’s not here,” Stella said, glancing around.

She could see why the vicar had asked to wait in this room. It was a masculine room, decorated with leather chesterfield chairs and couch, dark red walls, and a dark red and gold carpet, and was by far the warmest in the house. The glowing embers in the fireplace glinted off the gilded frame of a bird painting above the mantel.

“That’s probably his,” she said, noticing the empty cup and saucer on the square side table. “He must’ve already left.”

A few steps farther in, she caught a glimpse of a glass-paneled mahogany display case, against the side wall, filled with dozens of exotic birds of all shapes and sizes, many mounted on perching limbs. She eagerly strolled toward it. A glass dome filled with colorful butterflies sat in the front parlor at home. Each specimen had been collected and mounted by her mother before she died. Stella had peered into it every day when she was little, more often than not leaving behind fingerprint smudges, much to the maids’ chagrin. Yet no one had ever scolded her. The collection was one of the few reminders of Katherine Kendrick left in the house.

Stella stopped short. A wave of regret threatened to overwhelm her. She’d left so much behind. Tully and the trunks Daddy had allowed her, packed with the usual clothes, hats, shoes, jewelry, gloves, books, and the souvenir spoons she’d bought in Southampton and Hythe for a collection she no longer owned, were all that was left of her belongings, of her life back home.

I have to figure a way out of this.

“Where do you think the vicar is?” she asked, with a glimmer of hope. Perhaps the vicar could help her. Maybe he could dissuade Daddy and Lord Atherly from insisting on this ill-conceived marriage. If only she could talk to the vicar before Daddy did.

“Perhaps he’s fallen asleep on the sofa. I do hope he thought to remove his shoes.” Lord Lyndhurst frowned. “Reverend Bullmore,” he called, “you are late for tea, dear fellow.”

Stella and the viscount approached the high-backed couch from opposite sides. It was empty. But there on the carpet, a dark blotch seeping into the fibers that cushioned his graying head, was a gaunt man lying on his side. His unblinking eyes were open, and cookie crumbs clung to one corner of his upturned mouth.

“Oh!” Stella gasped, her hand covering her mouth. “Oh my God. Is that . . . ?”

“The vicar?” Lord Lyndhurst said. “Yes, I’m afraid it is.”

CHAPTER 5

“At what time did you discover the body, Lord Lyndhurst?”

Stella stared at the worn bottom of Inspector Brown’s left shoe as the kneeling policeman examined the body of Reverend Bullmore, crumpled on the library carpet. From where she sat, leaning against the bird display case, the couch hid the unfortunate vicar from view. But close her eyes and Stella could see every minute detail of the scene: the cookie crumbs on the vicar’s lips, the strands of gray hair sticking to the damp blood on his forehead, his left pant leg pushed up enough to expose his sock garter, his right eye partially open and staring at her, the starkness of the white collar around his neck. When had she first noticed the smear of blood on the side table? When had she moved from the couch to this distant chair? While Lord Atherly had been there, she’d stayed with the vicar, planting herself on the couch and nearly sitting on an open copy of the Sporting Life. She prided herself on having a strong constitution. She wasn’t one to faint at the slightest sight of blood or injury. Hadn’t she been the one who assisted when Tully was born? Hadn’t she nursed Daddy when he was thrown from Onondaga the day the stallion lost its shoe? How was this any different?

“Bloody hell. I don’t know,” Lord Lyndhurst said, combing his fingers through his hair. The other policeman, Constable Waterman, stood off to the side, near the fireplace, pad and pencil in hand, scribbling down whatever was said. He looked at the viscount expectantly. “I don’t remember.”

“Fulton had called us to tea,” Stella said. “It must’ve been around four o’clock.”

Lord Lyndhurst walked away from his position near the vicar’s body to stand next to Stella.

The inspector sat back on his heels and looked over the couch at them. He had a round, weathered face with a high forehead. Gray peppered his tidy mustache. He regarded Stella for a moment, a flash of anger in his wary eyes. Yet his tone was respectful and restrained when he spoke.

“Why is this young lady here? Shouldn’t she be with the others, my lord?”

“Yes,” Lord Lyndhurst said. “But she insisted, and she can be quite persuasive. Even Papa couldn’t get her to leave.”

When Lord Atherly had insisted she leave when he did, Stella had refused. Now she looked up at the viscount, standing with his hand resting on the back of her chair, almost protectively. He’d supported her decision to stay. Why?

“Miss Kendrick is my fiancée. We discovered the body together,” he said, as if answering her unspoken question.

“I wanted to . . . I needed to . . .” She stumbled over the words. “I thought . . .” She didn’t know what to think. A dead man lay on the other side of the chesterfield couch. “I couldn’t leave him alone. Not until you arrived. Not until someone could stay with him.”

“Right! Well, we’re here now. We’ll see to the vicar,” Inspector Brown said, not unkindly. “Any questions I have for you can keep.