His voice droned on, inaudible, except to the intent group facing him, above the subdued roar with which the voices of the crowd filled the building. And up and down the alleys between the stands flowed the human stream, now pursuing a slow and steady course, now eddying about some exhibit of special interest. The incident of Mr Pershore’s collapse had been witnessed by perhaps a couple of dozen people, none of whom knew that it had been fatal. So trivial a matter was scarcely a subject for comment. It may be that two acquaintances met by chance at one of the refreshment bars. ‘Hallo, Jimmy, what’s yours?’ ‘Mine’s a double whisky and a splash. Seen that new contraption of the Comet people’s yet?’ ‘Yes, I’ve just been having a look at it. Terrible crush on their stand. An old boy fainted just as I got there.’ ‘I don’t wonder. Felt like fainting myself when I was there this morning. Well, here’s luck!’ And the subject of Mr Pershore would be forgotten.

That evening, soon after ten, when the last of the public had been shepherded from the hall, and the exhausted staffs were clearing up for the night, the sales manager of the Solent Motor Car Company was fussing about his stand. He was not in the best of tempers. Solent and Comet cars were in much the same class, and an intense rivalry had always existed between them.

As it happened, the Solent people had made very few alterations to their models for this particular year, with the result that there was nothing startlingly novel exhibited on their stand. Since novelty is what attracts a very large percentage of visitors to the show, this had resulted in comparatively few inquiries. And yet the Solent stand, number 1276, was very favourably placed to attract notice. It was close to the entrance, almost the first thing to catch the visitor’s eyes as he entered the building.

The sales manager had a definite sense of grievance against his directors. If they hadn’t been such a sleepy lot of fatheads, they would have seen to it that the works got out something new, and not left it to the Comet people to steal a march on them like this. How the devil could a fellow be expected to sell cars to people if he had nothing out-of-the-way to show them?

He happened to glance through the window of a resplendent Solent saloon, and something lying on the floor at the back caught his eye. He opened the door, and picked up a mushroom-shaped piece of steel. ‘What the devil’s this?’ he exclaimed, frowning at the unfamiliar object.

One of his assistants, standing near by, answered him. ‘It looks like one of the exhibits from the Comet stand,’ he said.

‘What? One of those people’s ridiculous gadgets? How do you know that?’

The assistant, realising that he had given himself away, looked uncomfortable. ‘Well, I just took a stroll round their stand in my lunch hour,’ he replied sheepishly.

‘Oh, you did, did you? And I suppose you’ve been recommending people who come here to look at our stuff to follow your example. And how did this damn thing get on our stand? Perhaps you brought it back with you as a souvenir?’

The assistant attempted the mild answer which turneth away wrath. ‘I didn’t do that. But I’ll take it back to the Comet stand, if you like.’

‘Take it back? Let them come and fetch it if they want to. I’d have you know that employees of our firm aren’t paid to run errands for the Comet people. And see that you’re here sharp at nine tomorrow morning. I want some alterations made on this stand before the show opens.’ And, without vouchsafing a good-night, the sales manager departed.

His assistant watched him leave the hall. Then, since he had a friend in the Comet firm, he picked up the pressure valve, for such it was, and carried it to stand 1001. There he encountered the demonstrator who had been holding forth when Mr Pershore collapsed. ‘Hallo, George, this is a bit of your property, isn’t it?’ he said.

George Sulgrave recognised the pressure valve at once. ‘Where did you get that from, Henry?’ he asked suspiciously.

‘My Great White Chief found it inside one of the cars on our stand. Somebody must have picked it up, and then, finding it a bit heavy to carry about, put it down in the most convenient place.’

Sulgrave glanced round the stand. There was certainly a gap in the row of gadgets which bordered it. ‘Yes, that’s right,’ he said. ‘Some of these blokes would pinch the cars from under our very noses, if they thought they could get away with them. Thanks very much, Harry. We shall have to have these things chained to the floor, or something like that. How’s business on your stand?’

‘Simply can’t compete with the orders we’re getting,’ Harry lied readily. Loyalty to one’s firm is a greater virtue than truthfulness to one’s friend, as Sulgrave would have been the first to agree. ‘We’ve sold all our output for next year already.’

‘Same here,’ replied Sulgrave, no more truthfully than Harry. ‘You must come down and look us up when this confounded show is over. Irene will be glad to see you.’

‘Thanks very much. I’d like to run down one evening. Good-night, George.’

‘Good-night, Harry. Much obliged to you for your trouble.’

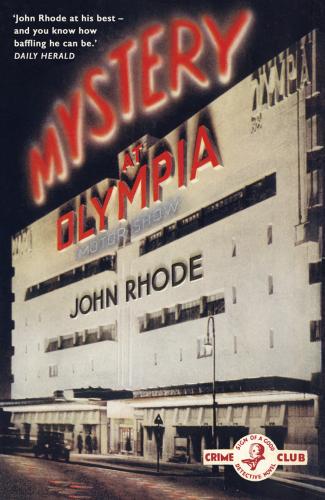

The attendants on the various stands completed their labours and went home. An almost uncanny hush settled upon the vast and now dimly lighted expanse of Olympia. Wrapped in a similar hush, and an even dimmer light, the body of Mr Nahum Pershore lay on a slab in the mortuary, rigid and motionless.

Mr Nahum Pershore had purchased all that messuage and tenement known as Firlands, Weybridge, some five years before his death. He had got it cheap, since, as the agent who had sold him the place had observed, it wasn’t everybody’s house.

This was quite true. Firlands was an outstanding example of the worst type of Victorian domestic architecture. One felt that the designer’s aim had been to achieve the maximum of pretentiousness without, and discomfort within. Still, nobody could deny that the house was ostentatious, and Mr Pershore liked ostentation. Besides, as Mr Pershore, who had amassed a considerable fortune by speculative building, could see at a glance, the house was solidly built and in excellent repair.

Mr Pershore was a bachelor, and he brought with him to Firlands his housekeeper, Mrs Markle. Long ago, fifty years at least, Nahum Pershore and Nancy Beard had played together in the builder’s yard belonging to Nahum’s father. They had grown up together, and perhaps, but for a series of events which had long ago lost their importance, they might have married. But, somehow, Nancy had drifted into matrimony with the son of Mr Markle, who kept the tobacconist’s shop over the way.

Nahum had risen in the world, thanks to a certain pertinacity and acumen. Nancy had not. After twenty years of married life, during which she had encountered many vicissitudes, she found herself a childless widow with nothing but her wits to support her. For a time she eked out an existence by obliging one or two families in the neighbourhood. In fact, she had achieved the status of a charwoman. And then one day, casting about for something more lucrative and less exacting, she thought of her old companion Nahum Pershore. She sat down and wrote him a letter. It was indicative of the gulf which had opened between them that in this she addressed him as ‘Dear Sir.’

Had she been inspired with some form of second sight, she could not have posted the letter at a more favourable moment. Mr Pershore was suffering from a profound weariness of housekeepers. They had come and gone, each more unsatisfactory than the last. Some had been young, and these had displayed tendencies which seriously alarmed the bachelor instincts of their employer. Others had been old, and these had been incompetent, and allowed the servants to do what they liked with them. He had just terminated the unpleasant business of giving notice to the last of them, when Mrs Markle’s letter arrived.

Nancy Beard, or Nancy Markle, as she was now! He