Coastal Sailing

Coastal sailing in unprotected waters normally involves longer voyages. A small crew soon tires of steering and it is here that the steering quality of the autopilot starts to matter. Sea state and factors such as tidal streams, shallows, narrow channels and winds from forward of the beam all impair the performance of autopilots. Rough seas make life difficult for them and as the waves increase in height and frequency the limits of a particular system quickly become apparent. Not surprisingly, intelligent and adaptive systems cope better with trying conditions than factory-set units which cannot be adjusted.

The general standard of equipment in this type of sailing is very high. The importance of good steering performance means that powerful inboard pilots connected directly to the main rudder are much more common; underpowered systems are soon exposed on the open sea. Although more powerful autopilots are inevitably hungrier, this rarely leads to battery problems since coastal sailing includes fairly regular motoring.

Blue Water Sailing

An autopilot stands or falls on its blue water performance. An underpowered system on the ocean reacts too slowly, too weakly and with too much delay to keep the boat on course, with increased yawing the result. The fear of losing steerage, of rounding up into the wind or worse and damaging the rig or boat, gives every sailor nightmares. If your autopilot is untrustworthy in a sea you could find yourself at the helm for a very long time.

The choice of autopilot becomes a survival issue for short-, double- or singlehanded sailing: a thousand miles at sea is more than enough to reveal the gulf between theory and reality, and choosing the wrong system could jeopardise the whole voyage. This is evidenced by the large number of would-be passage sailors who, reminded of the enormous importance of good self-steering on the initial leg of their voyage, stop off at Vilamoura, Gibraltar or Las Palmas to fit back-up systems, buy spare parts or add a windvane gear to supplement their autopilot. It is no coincidence that companies like Hydrovane and Windpilot deliver so many of their windvane steering systems to these strategic European jumping-off points!

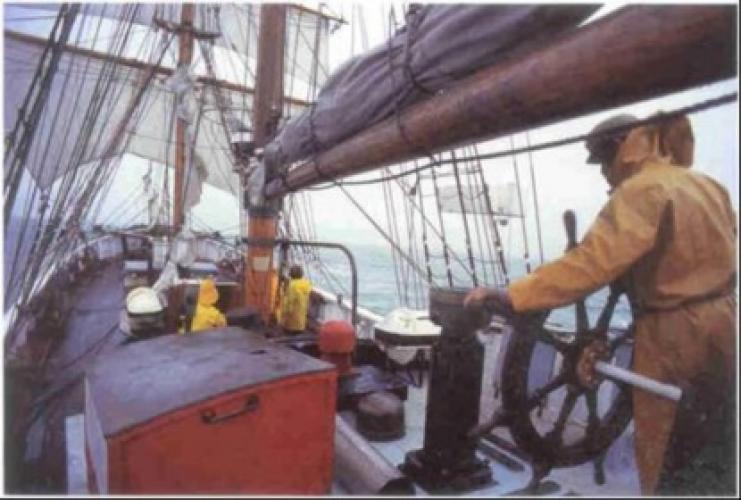

Although autopilots are standard on blue water yachts, the limitations of the different models (underpowered system, mechanical failures) dictate that they do not in fact steer continuously. A certain amount of manual steering is therefore unavoidable, something which is not always pleasant for the person on watch and which disrupts life aboard. The performance of electric autopilots drops sharply as wind and waves increase, so heavy weather steering often falls to a human helm as well. He or she of course has the advantage of being able to see (and hopefully avoid!) breaking waves.

Jimmy Cornell, organiser of races for long-distance recreational sailors, established in his debriefing after the EUROPA 92 round the world race that automatic systems steered for only 50% of the total time at sea. Manual steering was preferred the rest of time, either to improve speed and carry more sail area or because self-steering systems just were not able to cope with the conditions. Some crews simply did not trust their technology. Almost all the skippers used the autopilot when motoring through calms even if they chose to steer by hand when there was enough wind to sail.

The combination of off-the-wind sailing and long following seas characteristic of blue water passage making sets the stiffest challenge to any autopilot. The need for quick and forceful corrective rudder movements drives up the pilot’s power consumption and saps away at the vessel’s energy budget. This once again highlights the fundamental importance of responsible energy planning for any vessel intending to rely solely on an autopilot. The average power consumption of the autopilots used in the EUROPA 92 race was approximately 4.9Ah (average boat length 42 to 50 feet).

We must add at this juncture that the electromechanical reliability of autopilot systems still leaves something to be desired, particularly under the conditions likely in blue water sailing. This means in practical terms that sooner or later every autopilot is going to fail completely and manual steering will be unavoidable. One look at the list in the Las Palmas ARC office of the skippers requesting autopilot repairs is enough to set anybody thinking. Not surprisingly, bigger electric circuits with a larger number of components are more susceptible to gremlins, and the failure of a single, tiny component can be enough in some cases to cripple a whole system. Autohelm’s choice of black for its cockpit autopilots is particularly problematic in tropical climes since the colour causes thermally-induced operating temperatures to rise to the point where faults can occur. The sailor’s only remedy here is a tin of white paint!

It is striking that those who live aboard their boats tend to revert in the end to the most basic level of equipment, dispensing with any unnecessary gear and reducing clutter aboard; that a good self-steering system still merits a place underlines its importance. One-time pharmacist Lorenz Findeisen has been roving the Caribbean for years. His answer to the question of how his level of equipment has evolved?: “...Most of it broke a long time ago, but I’m not really bothered. As long as the anchor tackle, cooker and my windvane gear keep going I can carry on sailing.”

Autohelm is the market leader for inboard autopilots. Robertson has considerable experience as a system supplier for merchant vessels and is probably second. B&G, which concentrates mainly on precision transducers for racing boats, supplies quite a few of its NETWORK and HYDRA 2 systems to boats in this sector.

Racing

For our purposes races fall into two categories:

A. Fully crewed boats:

These are always steered by hand. This applies in all races, from round-the-buoys to the most famous of all, the Whitbread Round The World Race. Whitbread boats and others for the same kind of racing are extreme in all respects: extreme in their ultralight construction (ultralight displacement boats or ULDBs) which allows them to surf at great speed; extreme in their rigs, which are oversized and infinitely tweakable; and extreme in their aim of constantly maintaining absolute maximum speed. Extreme racing is an exhausting sport which pushes crews to their limit and, in the biggest races where expectant sponsors demand success and publicity, often beyond. When autopilots are used on boats of this nature (on delivery passages, for example), only computerised systems with ‘intelligent’ steering measure up (e.g. B&G HYDRA/HERCULES, AUTOHELM 6000/7000, ROBERTSON AP 300 X).

B. ULDBs in singlehanded races:

Competitors in the Vendée Globe, the singlehanded non-stop sprint around the world which starts from Les Sables d’Olonne in France every four years, rely exclusively on electric autopilots. The race, which includes 50 and 60-foot classes, is viewed by autopilot manufacturers as the ultimate test; the harshest conditions are guaranteed and the use of windvane steering systems is virtually out of the question (see Ocean racing section). Some older, slower vessels in the BOC Race (singlehanded around the world in stages) carry windvane steering systems as back-up, but here too autopilots do most of the steering.

ULDBs, which rarely have any kind of engine, rely on generators, solar cells or wind generators to maintain the power supply. The boats can reach speeds of 25 knots, so only the most powerful, ‘intelligent’ computerised systems are strong and fast enough to keep them on course. Autopilots are installed on every boat and steer most of the time. Although competitors in the long singlehanded races tend to follow a

10 minute waking/sleeping cycle, they never for one moment stop thinking about safety and boat speed. Nandor Fa lost about 12 kg in one Vendée Globe and knows only too well how the effects of this kind of