Salvatore, known as Salvo, has been living in Pisa with his family for years. He, too, is affected by the sicilitudine, a disease that makes us exiled children torn from our roots but always tightly linked to our native land.

I've known him since my days in the marching band when we both lived in the village. We had a good time between concerts, laughter, drinking and lots of friends. It was a lifetime ago.

For an unknown reason, I have always had a good feeling towards him, as if only beautiful things orbited around him. It is an irrational belief that comes out of my unconscious thoughts, so illogical that I feel it crystal clear! I am in this way. I follow instinct and live with passions.

Salvo told me that he wanted to publish on Facebook, through the successful Tuttogalatimamertino page, some videos about his grandfather, the homonymous Salvatore di Nardo (born in 1921), an Alpine in Russia with the Armir during the Second World War.

Nino Serio, the page administrator, raised some concerns as the material was complex and lasted more than three hours! It was a long interview with his grandfather about that tragic adventure, full of documentaries.

I could not stand that this story could end like this! It was the sparkle of that boy that did not give me peace. I suddenly felt within me a big craving to see that material, to know that story that had stayed buried for almost seventy years.

Those videos were like sparks that light a fire. The creative clapper set in motion, making my soul buzz. In me, the uncontrollable urge that I had already felt in my life and that I knew very well: to write.

I called Salvo Di Nardo.

“I’ll write a novel about it!” I told him point-blank.

He, touched, replied, “In my heart, that was what I wanted!”

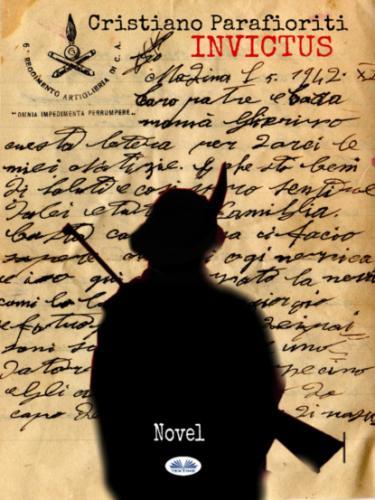

This novel is, therefore, based on a true story. Nevertheless, some characters, organizations, and circumstances may be the fruit of the author's imagination or, if they exist, used for narrative purposes.

Almost.

INTRODUCTORY ESSAY

THE ITALIAN CAMPAIGN OF RUSSIA

OF 1941-1943

AND ITS MEMORY

I’ve still in my nose the smell of grease on a red-hot machine-gun. I’ve still in my ears and even in my brain the crunching of snow under my boots, the coughs and sneezes from Russian lookouts, the sound of dry grass swept by the wind on the banks of the Don. I’ve still in my eyes the stars of Cassiopeia which hung above my head every night, and the bunker props above my head every day. And when I think about it all I feel the terror of that January morning when their gun Katiuscia first let off its seventy-two rocket-shells.1

This is the incipit of a famous autobiographical novel, The Sergeant in the snow, written by the Alpine Mario Rigoni Stern, soon destined to become the best-known literary testimony of the disastrous Italian campaign in Russia during the Second World War.

When, in June 1941, Hitler decided to wage war against the Soviet Union, triggering Operation Barbarossa, Mussolini responded by offering his willingness to support the German troops. The establishment of a Corps of Italian expedition to Russia (CSIR) left in mid-July for the eastern front under the orders of General Giovanni Messe.

The following year, combined with new corps in the Armir (Italian Army in Russia), it was deployed on the Don and couldn't resist the Soviet offensive that, between December 1942 and January 1943, would have decimated it. Numbers show the extent of the disaster.

Out of 230,000 Italians who left for the eastern front, one-third of these – about 95,000 – had lost their lives: dying in combat, dying of hardship and cold, during the retreat or the stages of transfer to the prison camps, sadly known as Davaj marches (from the term used to solicit the passage by the Russian escort soldiers). Without forgetting how many perished during the same imprisonment and the high number of those missing.

An event so fatal and fraught with consequences for thousands of Italian soldiers – swallowed up by the Russian steppe, plagued by tough Soviet resistance, as well as by adverse climatic conditions – and for their families, often destined to remain unaware of the fate of their relatives, ended up feeding a copious memoir, stimulated by the desire to account for a unique and devastating experience.

It is no coincidence that the Russian campaign – as the historian Maria Teresa Giusti, author of a valuable volume on the subject, pointed out – ended up as “one of the twentieth-century war events with the biggest impact on Italian collective memory”2.

A memory that is certainly uncomfortable, on the one hand, if we consider the fact that the war campaign was still an expression of the aggressive policy of Mussolini, but so disruptive due to the suffering and dramatic conditions of the retreat as to reveal the profound disillusionment with the regime. The bitter acknowledgment of the lack of training marked the participation of the Italian soldiers in the enterprise, which was opposed by the undoubted acts of heroism of those who were lucky enough to survive that terrible experience and return home. In this regard, it is interesting to re-read the authoritative testimony of another veteran, Nuto Revelli, among the first to denounce the dramatic conditions of the soldiers on the Russian front in his memorial writings:

Everything was unsuitable for the environment. Even the uniform, so green, made us targets. We had wagons of mountain warfare equipment, from ice crampons to avalanche ropes and rock ropes.

We were Alpine soldiers made for slow warfare, for walking. We had 90 mules for each company and four lorries for the whole battalion. Our weapons consisted of the Model 1891 rifle that had one advantage for its age: it was not muzzle loading. The equipment for the department was the Breda machine gun, which fired when well cleaned and oiled. We couldn’t, however, fire too many volleys, lest the barrel turned red, or the gun jammed, or fired on its own. The accompanying weapons – Brixia mortars, Breda machine guns, 81 mortars, and 47/32 cannons – were, for the most part, outdated and, in any case, not enough. Our only anti-tank weapon – the 47/32 cannon – could only pierce Italian tanks. Against Russian tanks, there was nothing to do.

Artillery in the divisional area consisted of museum equipment: the 75/13, the 100/17, utterly harmless and safe hand grenades, which did not always explode.

Means of a connection made for mountain warfare, unsuitable for long distances; the old faded flags, the heliographs, were of no use on that undulating terrain. The few radios, heavy and battered, were sometimes less fast than the order carriers.

No mines, no flares, no reticulates, no tracer bullets. And little ammunition, almost depleted.

The equipment was the same as on the Western Front from the battle of June 1940. Uniforms made of the worst wool, shoes of stiff, dry leather that looked like paper. The foot cloths seemed to have been made on purpose to block the blood circulation, favouring heating or freezing.

We were not tanks. We were mountain troops, poorly armed, poorly equipped for mountain warfare. Throwing ourselves into the plains, where armoured warfare was running fast, meant going in blind.3

Historiographical research confirmed it was a disaster. A disaster made worse by the grave shortcomings of the Italian army's war equipment and the laxity with which the military commanders and Mussolini approached the enterprise.

The Duce was sure that the war would be over soon, mainly due to the training and firepower of the German ally. Therefore, he had refrained from mobilising the country for the campaign – as had happened during the conquest of Ethiopia. The affair resulted in the worst collapse suffered by the Italian army.

To be