This book is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a foundation established to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals.

The cuneiform inscription that serves as our logo and as a design element in Liberty Fund books is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash.

Introduction, editorial annotations, and index © 2011 by Liberty Fund, Inc.

The text of this edition is the translation by Thomas Jefferson, published in 1817 by Joseph Milligan.

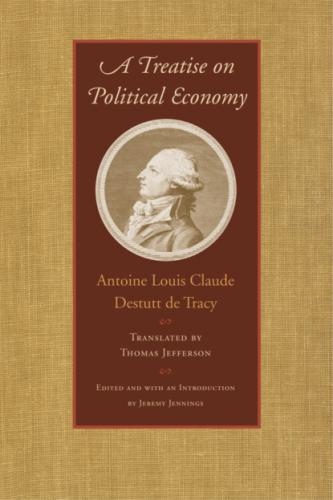

Cover image is an engraving, circa 1761–1790, by Victor Texier after Charles Toussaint Labadye, from the Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY.

This eBook edition published in 2012.

eBook ISBN: E-PUB 978-1-61487-241-2

Contents

Introduction to the Liberty Fund Edition

A Treatise on Political Economy

Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Joseph Milligan

Prospectus, by Thomas Jefferson

Supplement to the First Section of the Elements of Ideology

First Part of the Treatise on the Will and Its Effects: Of Our Actions

CHAPTER 2: Of Production, or of the Formation of Our Riches

CHAPTER 3: Of the Measure of Utility or of Values

CHAPTER 4: Of the Change of Form, or of Manufacturing Industry, Comprising Agriculture

CHAPTER 5: Of the Change of Place, or of Commercial Industry

CHAPTER 7: Reflections on What Precedes

CHAPTER 8: Of the Distribution of Our Riches amongst Individuals

CHAPTER 9: Of the Multiplication of Individuals, or of Population

CHAPTER 10: Consequences and Developments of the Two Preceding Chapters

CHAPTER 11: Of the Employment of Our Riches, or of Consumption

CHAPTER 12: Of the Revenues and Expenses of a Government, and of Its Debts

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to the staff of Liberty Fund for their invaluable support and encouragement and wish, in particular, to thank Christine Henderson. In addition, I would also like to thank Henry Clark for his helpful suggestions with regard to the introduction and translation of the text. Finally, my thanks go to the staff of the Rare Books Room at the British Library.

Introduction to the Liberty Fund Edition

Antoine Louis Claude Destutt de Tracy was born in 1754, the son of a distinguished aristocratic and military family that traced its lineage back to 1419, the year in which four Scottish brothers named Strutt joined the army of the future Charles VII of France to fight against the English. At his father’s deathbed, the young Antoine promised to pursue a military career. This he duly did, joining the company of the Black Musketeers at the age of 14, later attending the school of artillery in Strasbourg, and eventually serving in the Revolutionary army as second-in-command of the cavalry under Lafayette in the war against Austria. After inheriting the lands of his family estate, in 1779 he married Emilie-Louise de Durfort de Civrac, a cousin of the Duke of Orleans. The king and queen of France signed their marriage certificate.

As the first stages of the French Revolution began to unfold, Destutt de Tracy was elected to represent the nobility of the Bourbonnais at the Estates General, called by Louis XVI to meet at Versailles in May 1789. We know little of his actions or views at this time, but it seems that he was in favor of the reform of the old monarchical and feudal system. This became clear in April 1790, when, first in a brief parliamentary speech and then in a short pamphlet, he sought to refute Edmund Burke’s charge that the Revolution would end in bloodthirsty disaster.1 Contrary to the claims of his illustrious adversary, Destutt de Tracy maintained that France was in the process of establishing a constitutional and hereditary monarchy that would guarantee the liberties of the individual. He was not of the opinion that France should slavishly imitate English institutions.

This early optimism was quickly dissipated as the Revolution pursued a course closer to the one predicted by Burke. On the grounds of his aristocratic birth, Destutt de Tracy was arrested and imprisoned in November 1793, securing his release the following October in the wake of the overthrow of Maximilien Robespierre and the end of the Reign of Terror. He had been lucky to escape the guillotine. It is in this experience that the origins of Destutt de Tracy’s attempt to outline what he came to describe as the science of “ideology” can be first discerned.

Despite pursuing a military