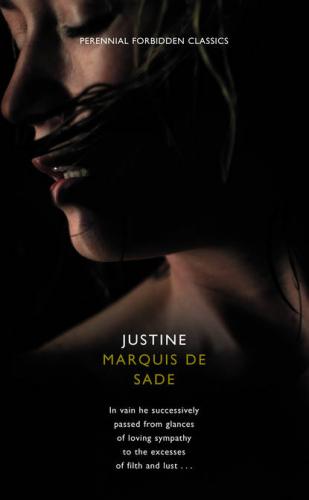

Justine

or The Misfortunes of Virtue

D. A. F. Marquis De Sade

Table of Contents

Harper Perennial Forbidden Classics

…A little less debauchery and he would have had his will of me; but the fires of Dubourg’s ardour were extinguished by the effervescence of his attempts.

The triumph of philosophy would be to reveal, amply and lucidly, the means by which providence attains her ends over man; and, accordingly, it would trace those lines of conduct which might enable this unfortunate biped individual to avoid, while treading the thorny path of life, those bizarre caprices of a fate which has twenty different names, but which, as yet, has never clearly been defined.

For although we may fully respect our social conventions, and dutifully abide by the restrictions which education has imposed on us, it may unfortunately happen that through the perversity of others we encounter only the thorns of life, whilst the wicked gather nothing but roses. Things being so, is it not likely that those devoid of the resources of any firmly established virtues may well come to the conclusion suggested by such sad circumstances – that it were far better to abandon oneself to the torrent rather than resist it? Will it not be said that virtue, however fair she may be, becomes the worst cause one can espouse when she has grown so weak that she cannot struggle against vice? Will it not equally be said that, living in a century so thoroughly corrupt, the wisest course would be to follow in the steps of the majority? May we not expect some of our more educated folk to abuse the enlightenment they have acquired, saying with the angel Jesrad of Zadig that there is no evil which does not give birth to some good – adding that, since the imperfect constitution of our sorry world contains equal amounts of evil and of good, it is essential that its balance be maintained by the existence of equal numbers of good and wicked people. And will they not finally conclude that it is of no consequence in the general plan whether a man is good or wicked by preference; and that if misfortune persecutes virtue and prosperity almost always accompanies vice, things being equal in the sight of nature, it seems infinitely better to take one’s place among the wicked, who prosper, than among the virtuous, who perish.

Therefore it is important to guard against the sophisms of a dangerous philosophy, and essential to show how examples of unfortunate virtue, presented to a corrupted soul which still retains some wholesome principles, may lead that soul back to the way of godliness just as surely as if her narrow path had been bestrewn with the most brilliant honours and the most flattering of rewards. Doubtless it is cruel to have to describe, on the one hand, a host of misfortunes overwhelming a sweet and sensitive woman who has respected virtue above all else, and – on the other – the dazzling good fortune of one who has despised it throughout her life. But if some good springs from the picture of these fatalities, should one feel remorse for having recorded them? Can one regret the writing of a book wherein the wise reader, who fruitfully studies so useful a lesson of submission to the orders of providence, may grasp something of the development of its most secret mysteries, together with the salutary warning that it is often to bring us back to our duties that heaven strikes down at our side those who best fulfil her commandments?

Such are the thoughts which caused me to take up my pen; and it is in consideration of such motives that I beg the indulgence of my reader for the untrue philosophies placed in the mouths of several of my characters, and for the sometimes rather painful situations which, for truth’s sake, I am obliged to bring before his eyes.

The Comtesse de Lorsange was one of those priestesses of Venus whose fortune lies in an enchanting figure, supported by considerable misconduct and trickery, and whose titles, however pompous they may be, are never found save in the archives of Cythera, forged by the impertinence which assures them, and upheld by the stupid credulity of those who accept them. Brunette, vivacious, attractively made, she had amazingly expressive dark eyes, was gifted with wit, and possessed, above all, that fashionable cynicism which adds another dash of spice to the passions, and which makes infinitely more tempting the woman in whom it is suspected. She had, moreover, received the best possible education. Daughter of a very rich merchant of the rue Saint-Honoré, she had been brought up, with a sister three years younger than herself, in one of the best convents in Paris; where, until she was fifteen years old, nothing in the way of good counsel, no good teacher, worthwhile book, or training in any desirable accomplishment, had been refused her. Nevertheless, at that age when such events are most fatal to the virtue of a young girl, she found herself deprived of everything in a single day. A shocking bankruptcy plunged her father into such a cruel situation that all he could do to escape the most sinister of circumstances was to fly speedily to England, leaving his daughters in the care of a wife who died of grief within eight days of his departure. One or two of their few remaining relatives deliberated on the fate of the girls, but as all that was left to them totalled a mere hundred crowns each, it was decided to give them their due, show them the door, and leave them mistresses of their own actions.

Madame de Lorsange, who at that time was known as Juliette, and whose wit and character were already almost as mature as they were when she had reached the age of thirty – which was her age at the time of our story – felt only pleasure at her freedom, and never for an instant dwelt on the cruel reverses which had broken her chains. Justine, her sister, however, just turned twelve, and of a sombre and melancholy turn of mind, was endowed with an unusual tenderness accompanied by a surprising sensitivity. In place of the polish and artfulness of Juliette, she possessed only that candour and good faith which were to lead her into so many traps, and thus felt all the horror of her position.

This young girl’s features were totally different from those of her sister. The one held just as much of artifice, flirtation, and guile, as the other did of delicacy, timidity, and the most admirable modesty. For Justine had a virginal air, great blue eyes gentle with concern,