Introduction

Eleanor of Aquitaine (French) Aliénor d'Aquitaine, Éléonore, was Queen Consort of France (1137–1152) and England (1154–1189) and Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right. As a member of the Ramnulfids (House of Poiters) rulers in southwestern France, she was one of the most powerful and wealthiest women in western Europe during the High Middle Ages. She was a patron of literary figures such as; Robert Wace, ( c. 1110 – after 1174), was a Norman poet, Benoit de Sainte-Maure (wrote two historical poems, or estoires: the Roman de Troie (ca. 1165) and the Chronique des ducs de Normandie) and Bernart de Ventadorn who was a prominent troubadour of the classical age of troubadour poetry, like the rappers today but much more eloquent and literate.

She led armies several times in her life and was a leader of the Second Crusade with the understanding that she never drew blood and her personal staff was nearly as large as the army she led. There was no question that she utilized her natural talent in the bedroom to become a feminine icon and power broker as juxtaposed to a future heroine St. Joan of Arc. Had Eleanor lived in the 21st century she no doubt would have led the vanguard of women suing all the men she bedded for sexual duress.

As Duchess of Aquitaine, Eleanor was the most eligible bride in Europe. Three months after becoming duchess upon the death of her father, William X, she married King Louis VII of France, son of her guardian, King Louis VI. As Queen of France, she participated in the unsuccessful Second Crusade. Soon afterwards, Eleanor sought an annulment of her marriage, but her request was rejected by Pope Eugene III who ostensibly coined the phrase, "You made your bed, now sleep in it!" However, after the birth of her second daughter Alix, Louis agreed to an annulment, as fifteen years of marriage had not produced a son. The marriage was annulled on 11 March 1152 on the grounds of consanguinity (within the same blood or origin; specifically : descended from the same ancestor in the fourth degree.) Their daughters were declared legitimate and custody was awarded to Louis, while Eleanor's lands were restored to her. Proving once again Eleanor to be an outright whore, preferring wealth granted to her over precious blood given in child birth.

As soon as the annulment was granted, Eleanor became engaged to the Duke of Normandy (with whom she had conjugal activity during her marriage and may have fathered one of her daughters), who became King Henry II of England in 1154. Henry was her third cousin and eleven years younger. The couple married on Whitsun, (Which is the seventh Sunday after Easter and is the name for the Christian festival of Pentecost among Anglicans) on 18 May 1152, eight weeks after the annulment of Eleanor's first marriage, in Poiter's Cathedral and the bride wore white, of course! Over the next thirteen years, she bore eight children: five sons, three of whom became kings; and three daughters. However, Henry and Eleanor eventually became estranged. Henry imprisoned her in 1173 for supporting their son Henry's revolt against him. She was not released until 6 July 1189, when Henry died and their second son, Richard the Lionheart, ascended the throne.

As Queen Dowager, (is a title or status generally held by the widow of a king) Eleanor acted as Regent, (is a female monarch, equivalent in rank to a king, who reigns in her own right, in contrast to a queen consort, who is the wife of a reigning king, or a queen regent, who is the guardian of a child monarch and reigns temporarily in the child's stead), while Richard went on the Third Crusade; on his return Richard was captured and held prisoner. Eleanor lived well into the reign of her youngest son, John. She outlived all her children except for John and Eleanor. But, forgive me, please...I am well ahead of my story and must provide a historical review (a bit dry) but necessary in order that my dear readers know and feel the scope of this woman's life...frankly, I loved this part of the work since I have a learning disability and must not only read but write each word in order to remember the history lesson.

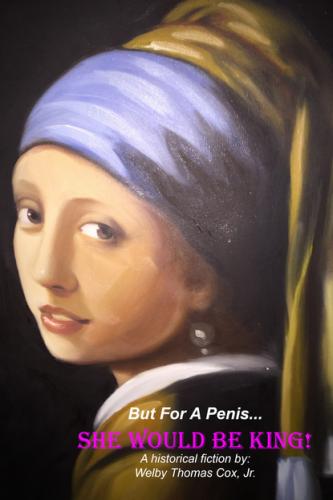

...But For A Penis

SHE WOULD BE KING!

ELEANOR OF AQUITAINE: EARLY LIFE

Eleanor was born in what is now southern France, most likely in the year 1122. She was well educated by her cultured father, William X, Duke of Aquitaine, thoroughly versed in literature, philosophy, and languages and trained to the rigors of court life when she became her father’s heir presumptive at the age 5. An avid horsewoman, she led an active life until she inherited her father’s title and extensive lands upon his death when she was 15, becoming in one stroke duchess of Aquitaine and by far the most eligible single young woman in Europe. She was placed under the guardianship of the king of France, and within hours was betrothed to his son and heir, Louis. The king sent an escort of 500 men to convey the news to Eleanor and transport her to her new home.

But let us fast forward some thirty odd years to see what transpired making her one of the most prolific dam's of leaders in the world for all times.

In January 1169, Henry II and Louis VII met at Montmirail in Maine to negotiate (it was hoped) a lasting peace settlement. For two years both kings had been engaged in a futile war that, while being both expensive and destructive, had gained no advantage for either. Among other matters an attempt was made to reconcile Henry with Thomas Becket, but both king and archbishop were incapable of compromise. The principal business, however, was to secure Louis’s agreement to Henry’s plans for a dynastic settlement that would divide the Angevin empire among his sons and enable him to ensure the local barons’ recognition of their right to succeed. The settlement would also help the English king to subdue rebellious vassals who, in almost every part of his French domains, had recently been so troublesome. Louis agreed readily, only too pleased to guarantee the future division of his overmighty neighbour’s empire. Eleanor, of course, was not consulted. But she must have seen in Montmirail her opportunity to overthrow her husband and to regain complete independence.

The eldest surviving Plantagenet son, Henry, was to have England, Normandy, Maine and Anjou — his father’s own inheritance — together with the overlordship of Brittany. To ensure his undisputed succession, the Capetian custom was adopted of crowning the fifteen-year-old boy king in his father’s lifetime. The coronation took place on 24 May 1170 in Westminster Abbey and was performed by the archbishop of York (Thomas Becket having refused an invitation to return to England to do so). No pomp was lacking, the crown made by the London goldsmith William Cade costing nearly forty pounds... an enormous sum for the period. His wife Margaret — Louis’s daughter — was not crowned with him, a strange and insulting omission. At the coronation banquet the old king, as he was henceforth to be known, waited on the young king. The archbishop of York commented unctuously that no prince in all the world was waited on by a king. The youth replied, ‘It is not unfitting that the son of a mere count should wait on the son of a king’. The retort tells us a good deal about the young king, who was both conceited and ungrateful. From now on he had his own household, and contemporary writers refer to him as ‘Henry III’, an eloquent testimony as to how seriously they took his kingship. It is said that Eleanor was delighted by her son’s elevation. There was, it is clear, considerable affection between her and the young king, who sometimes visited Poitiers with his wife. No doubt the queen was already working to make him her ally against the old king.

We know nothing about Eleanor’s relations with her children during their childhood. According to the custom of the age they would have been brought up away from her, first by foster-mothers and then in the households of trusted magnates, although she must have seen them all from time to time. Nevertheless it is possible that she saw more of Richard, the fourth child of her second marriage, and from a very early age, because...as the heir to Aquitaine from his cradle... he was the very center of her hopes of regaining power. From the time of Montmirail at least, when he was still only twelve, he was Eleanor’s constant companion. In view of his later reputation for homosexuality, it is not too much to suppose that the queen was one of those excessively dominant mothers who transform their sons into little lovers; and it is likely that Richard was the only man in her life and she the only woman in his.

At Montmirail Louis both recognized Richard’s claim to Aquitaine and betrothed him to Alice, his daughter by his second marriage, who was sent to England to be brought up. No doubt Eleanor rejoiced when, in that same year of 1169, king Henry ordered that Richard be proclaimed count of Poitiers; and in the summer