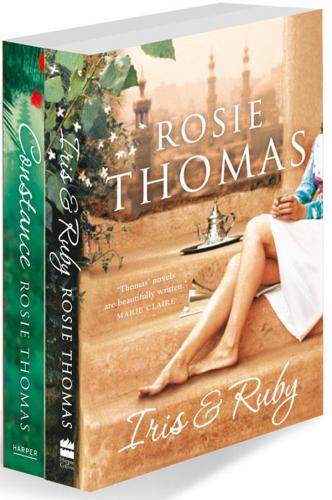

Iris and Ruby

Constance

Rosie Thomas

Table of Contents

Extract from The Kashmir Shawl

ROSIE THOMAS

Iris and Ruby

For Louis, Solomon and Misty. The new generation

Contents

I remember.

And even as I say the words aloud in the silent room and hear the whisper dying away in the shadows of the house, I realise that it’s not true.

Because I don’t, I can’t remember.

I am old, and I am beginning to forget things.

Sometimes I’m aware that great tracts of memory have gone, slipping and melting away out of my reach. When I try to recall a particular day, or an entire year, even a damned decade, if I’m lucky there are the bare facts unadorned with colour. More often than otherwise there’s nothing at all. A blank.

And when I can remember where I have lived, and who I was living with and why, if I try to conjure up what it was like to be there, the texture of my life and what impelled me to wake up every morning and pace out the journey of the day, I cannot do it. Familiar and even beloved faces have silently melted away, their names and the dates of precious initiations and fond anniversaries and events that once seemed momentous, all collapsed and buried beyond reach.

The disappearing is like the desert itself. Sand blows from the four corners of the earth and it builds up in slow drifts and dun ripples, and it blurs the sharpest, proudest structures, and in the end obliterates them.

This is what’s happening to me. The sands of time. (It is a no less accurate image for being a cliché.)

I am eighty-two. I am not afraid of death, which after all can’t be far away.

Nor do I fear complete oblivion, because to be oblivious means what it says.

What does frighten me is the halfway stage. I am afraid of reduction. After a lifetime’s independence – yes, selfish independence as my daughter would rightly claim – I am terrified of being reduced to childhood once more, to helplessness, to seas of confusion from which the cruel lucid intervals poke up like rock shoals.

I don’t want to sit in my chair and be fed spoonfuls of pap by Mamdooh or by Auntie; much less do I want to be handed over to medical professionals who will subject me to well-intentioned geriatric care.

I know what that will be like. I am a doctor myself and as well as remembering too little, I have seen too much.

Now Mamdooh is coming. His leather slippers make a soft swish on the boards of the women’s stairway. There is nothing wrong with my hearing. The door creaks open, heavy on its hinges, so that I can see a corner of the pierced screen that hides the gallery from the celebration hall. A light shining through the screen stipples the floor and walls with crescents and stars.

‘Good evening, Ma’am Iris,’ Mamdooh softly says. The deferential form of address has become so elided, so rubbed with usage that it is a pet name now, Mum-reese. ‘Have you been sleeping perhaps?’

‘No,’ I tell him.

I have been thinking. Turning matters over in my mind.

Mamdooh puts down a tray. A glass of mint tea, sweet and fragrant. A linen napkin, some triangles of sweet pastry that I do not want. I eat very little now.

The shiny coffee-brown dome