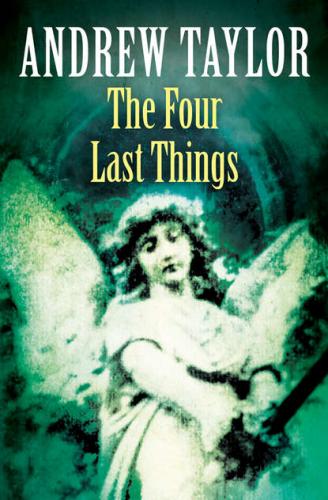

ANDREW TAYLOR

THE FOUR LAST THINGS

CONTENTS

‘In brief, we all are monsters, that is, a composition of Man and Beast …’

Religio Medici, I, 55

All his life Eddie had believed in Father Christmas. In childhood his belief had been unthinking and literal; he clung to it for longer than his contemporaries and abandoned it only with regret. In its place came another conviction, another Father Christmas: less defined than the first and therefore less vulnerable.

This Father Christmas was a private deity, the source of small miracles and unexpected joys. This Father Christmas – who else? – was responsible for Lucy Appleyard.

Lucy was standing in the yard at the back of Carla Vaughan’s house. Eddie was in the shadows of the alleyway, but Lucy was next to a lighted window and there could be no mistake. It was raining, and her dark hair was flecked with drops of water that gleamed like pearls. The sight of her took his breath away. It was as if she were waiting for him. An early present, he thought, gift-wrapped for Christmas. He moved closer and stopped at the gate.

‘Hello.’ He kept his voice soft and low. ‘Hello, Lucy.’

She did not reply. Nor did she seem to register his use of her name. Her self-possession frightened Eddie. He had never been like that and never would be. For a long moment they stared at each other. She was wearing what Eddie recognized as her main outdoor coat – a green quilted affair with a hood; it was too large for her and made her look younger than she was. Her hands, almost hidden by the cuffs, were clasped in front of her. He thought she was holding something. On her feet she wore the red cowboy boots.

Behind her the back door was closed. There were lights in the house but no sign of movement. Eddie had never been as close to her as this. If he leant forward, and stretched out his hand, he would be able to touch her.

‘Soon be Christmas,’ he said. ‘Three and a half weeks, is it?’

Lucy tossed her head: four years old and already a coquette.

‘Have you written to Santa Claus? Told him what you’d like?’

She stared at him. Then she nodded.

‘So what have you asked him for?’

‘Lots of things.’ She spoke well for her age, articulation clear, the voice well-modulated. She glanced back at the lighted windows of the house. The movement revealed what she was carrying: a purse, too large to be hers, surely? She turned back to him. ‘Who are you?’

Eddie stroked his beard. ‘I work for Father Christmas.’ There was a long silence, and he wondered if he’d gone too far. ‘How do you think he gets into all those houses?’ He waved his hand along the terrace, at a vista of roofs and chimneys, outhouses and satellite dishes; the terrace backed on to another terrace, and Eddie was standing in the alley which ran between the two rows of backyards.

Lucy followed the direction of his wave with her eyes, raising herself on the toes of one foot, a miniature ballerina. She shrugged.

‘Just think of them. Millions of houses, all over London, all over the world.’ He watched her thinking about it, her eyes growing larger. ‘Chimneys aren’t much use – hardly anyone these days has proper fires, do they? But he has other ways in and out. I can’t tell you about that. It’s a secret.’

‘A secret,’ she echoed.

‘In the weeks before Christmas, he sends me and a few others around to see where the problems might be, what’s the best way in. Some houses are very difficult, and flats can be even worse.’

She nodded. An intelligent child, he thought: she had already begun to think out the implications of Santa Claus and his alleged activities. He remembered trying to cope with the problems himself. How did a stout gentleman carrying a large sack manage to get into all those homes on Christmas Eve? How did he get all the toys in the sack? Why didn’t parents see him? The difficulties could only be resolved if one allowed him magical, or at least supernatural, powers. Lucy hadn’t reached that point yet: she might be puzzled but at present she lacked the ability to follow her doubts to their logical conclusions. She still lived in an age of faith. Faced with something she did not understand, she would automatically assume that the failure was hers.

Eddie’s skin tingled. His senses were on the alert, monitoring not only Lucy but the houses and gardens around them. It was early evening; at this time of year, on the cusp between autumn and winter, darkness came early. The day had been raw, gloomy and damp. He had seen no one since he turned into the alleyway.

Traffic passed in the distance; the faint but insistent rhythm of a disco bass pattern underpinned the howl of a distant siren, probably on the Harrow Road; but here everything was quiet. London was full of these unexpected pools of silence. The streetlights were coming on and the sky above the rooftops was tinged an unhealthy yellow.

‘You look as if you’re going out.’ Eddie knew at once that this had been the wrong thing to say. Once again Lucy glanced back at the house, measuring the distance between herself and the back door. Hard on the heels of this realization