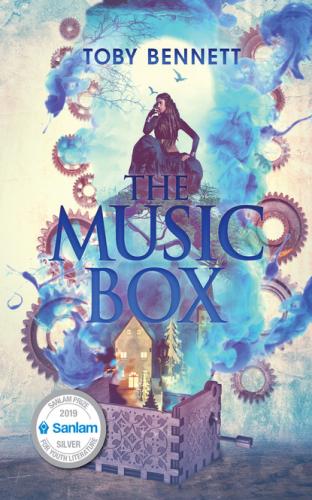

THE

MUSIC

BOX

TOBY BENNETT

Tafelberg

This book was awarded

a Sanlam Prize for

Youth Literature 2019

For those who’ve walked the long road with me and took my weight when I faltered.

The Music Box

The metallic notes ping and echo through the tiny shell,

The dancer makes her endless circuit, around and around –

No one ever wonders if she gets sick of the tune.

CHAPTER 1

Crossed Wires

Maribell Schmitt almost dropped the tray of muffins for the church sale at the sound of the telephone.

“You been fiddlin’ again, John?” She shouted into the gloom.

She set the tray on the nearest table and glared down the ill-lit corridor. The threadbare carpeting had borne the brunt of her broad, sensible shoes for more than a decade and a half; the floorboards beneath groaned in protest as she advanced on the shrill ringing.

“I told you we don’t need that contraption. Nothing but trouble out there and we don’t need that … Not since your father …” The strain of sustaining a one-sided argument over the insistent rattle of the old phone’s decrepit bell had already become too much. She grabbed the handset with one oversized mitt.

“Hello?” She hollered into the mouthpiece, squeezing the masking tape on the handle until the plastic beneath popped and the earpiece squealed, hissing static.

“Hello? Is this Mrs Schmitt?” A tentative voice.

“You sellin’ something, mister?” Maribell asked, immediately distrustful of the quiet, affected voice.

“Not as such. You are Mrs Schmitt, I take it?” There was an unpleasant firmness to the question.

Maribell hated people who asked questions when they already knew the answers.

“Well, I’m not mister, am I?”

“Quite.” The caller had found his feet and was plunging ahead with the conversation, seemingly indifferent to Maribell’s reluctance. “My name is Laurence Carter. I’m phoning to inform you that your son, Jonathan Schmitt, has gained acceptance to our scholarship programme.”

“Thought you said you weren’t sellin’ anything,” Maribell growled. Her eyes flicked back down the hall.

What had John been up to?

“I assure you I’m not selling a thing. Jonathan is probably one of the highest-scoring candidates we have ever had; tuition at Rosewood Academy would be at almost no cost to you, and certainly of a completely different standard to …” There was a rustle of papers and a crackle on the line. “St Martin’s.”

“And what’s wrong with my son’s school?” Maribell asked.

What had he done now?

“Nothing, I’m sure, but there’s no way a school of that calibre can properly nurture a talent like your son’s. It is only a publicly funded school, after all.”

“It’s a good church school, is what you mean. Not some fancy book-worshippin’ place where people get above themselves, thinkin’ they can tell us all what’s what,” she sputtered.

“Please, Mrs Schmitt, our religious facilities are not –”

“Any of my goddamned business, just like my son is none of yours. Jonathan’s father, God rest him, went to St Martin’s and he turned out smart enough. If my boy’s as smart as you say, then he don’t need help to make his way!” Maribell was breathing hard and she felt an immense weight pressing against her heavy chest.

“Mrs Schmitt, please listen to me. This is about what’s best for Jonathan –”

“You’re saying his own mother doesn’t know what that is?” she shrieked.

“Not at all,” Mr Carter protested, “but …”

Anything else he had to say was lost in the sound of the handset being repeatedly slammed against the wall and the scream transmitted by the broken entrails of the receiver in Maribell Schmitt’s hand.

“Let’s see you fix it this time, you miserable son of a …”

* * *

John didn’t hear the last word. He didn’t need to; he’d heard the accusation many times before. As usual she said it without any sense of irony. He could guess what had set her off. He should never have fixed the phone, but it bothered him to leave things broken. He’d resisted the urge for as long as he could, but it was as if the battered device had been calling to him.

It didn’t do to scare his mother though, and nothing scared Maribell like her son’s uncanny talent with broken things. She was never happy when he repaired something around the house; instead, she said he was cursed. No doubt his latest work would lead to hours of repentant prayers and admonitions. John wished he could make his mother happy, but certain problems tugged at his awareness like an aching tooth until he had to fix them. The phone, for instance, had bothered him every time he’d walked past, until he’d had no choice but to set it right, even though he’d known how Maribell would react.

The Devil’s work! That was what she called his talent.

John did his best not to remind his mother what he could do.

Even when he tried to pretend he was normal, she treated him as though he were possessed. When he was younger John had felt shame, but more recently a sliver of resentment had begun to prick at his mind.

John had sat through his fair share of sermons, but nothing he’d heard in Dowdale’s small church or St Martin’s chapel was more than a dull echo of his mother’s fervour. She claimed she saw the Devil in him. That was why he could only leave the house to go to school, and why she always insisted he come straight home. John knew that she wouldn’t have allowed him to leave at all if she could help it, but Dowdale was small enough that she couldn’t have kept him entirely cooped up without the town talking – apparently when it came to facing the Devil or the neighbours, the neighbours won out.

As he’d grown older, John had realised that no one else saw the Devil, but Maribell did seem to have an uncanny knack for knowing when her son had used his talents. She claimed her bones ached every time he fixed something tricky.

Even now his mother was twice his size, and it didn’t do to make her bones ache.

It was tempting to imagine that it was all in his mother’s mind. The kids at school laughed at some of the things their mothers said and would have mocked any suggestion that mad old Mrs Schmitt was anything more than two sticks shy of the full basket, but John knew better – he felt it.

He couldn’t explain how his mother felt it too but there was something unnatural to his talent. The truth was, John could fix anything if he tried hard enough. The few times he’d attempted to explain that to someone else, he’d been met with disbelief and confusion. Others seemed incapable of understanding that “anything” wasn’t simply an expression; he was being quite literal. When he sat down to repair something, the process felt just short of magic. He didn’t understand how, but he always knew what needed to be done when he saw something broken. It was almost like he could see into whatever he was looking at – like X-ray vision in the comics he wasn’t supposed to read.

It was the kind of gift that should have made someone happy, but it never seemed to work that way. It was one thing to know how to repair a watch or a toy, another to see everything that went wrong