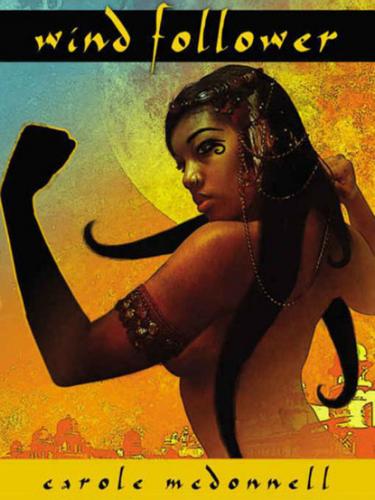

WIND FOLLOWER

CAROLE McDONNELL

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copryight © 2007 by Carole McDonnell

Cover art copyright © 2007 by Tim Lantz

Cover design copyright © 2007 by Stephen H. Segal

Published by Wildside Press LLC.

www.wildsidebooks.com

DEDICATION

In memory of my mother, Louise Stewart

*

For Luke, Logan and Gabe

QUOTATIONS

He gave them power and authority over all devils, and to cure diseases.—Luke 9:1

I write unto you, young men, because you have overcome the wicked one.—I John 2:13

Little children, keep yourselves from idols.—I John 5:21

FOREWORD

These are the words that Loic tyu Taer and Satha tya Monua spoke to our ancestors on the day the Angleni gathered us to this place. How briefly that bright light shone—yet how powerfully! Nevertheless, all is not lost. Tell your children this prophecy, and let your children tell their children, and those children must tell the future generations—because the prophesied time will come. In the last days, the light will shine again with power and permanence. Use these memories as a beacon, my children, for the time will come when the Great Chief will return to us our land and all that is ours.

LOIC: The Reaping Moon-First Harvest Moon

I will tell you first how Krika died. Okiak, his father and the chief shaman of our clan, brought Krika before the elders at the Spirit Shrine, the sacrificial mound we called Skull Place. My friend was bound, hand and foot, and the skin of his face had been flayed away so that all the muscles and bones beneath his right eye were exposed and glistening. He was weeping and crying out for mercy, choking on his tears. This surprised me, but I forgave it. Who could bear such pain without weeping?

Okiak lifted the shuwa, already reddened with his son’s blood, and there—surrounded by bones and burned flesh, remnants of the monthly sacrifices—he shouted, “My son has not obeyed me. I have warned him time and times to pay obeisance to our spirits, but he has refused.”

The spirits had ordered his death. I stood far off, struggling with my father and Pantan. Their hands held me fast and kept me from racing to Krika’s side.

Nevertheless, I called out, shouted aloud for everyone to hear. “Are the spirits so puny and helpless they must force people to worship them?”

All eyes rebuked me, yes, all the elders of the Pagatsu clan, and Father yanked me back by my arm. “Be careful, son,” he said, “lest the spirits also demand your life.”

I glared at him. “And if they did, would you be so weak as to comply?”

He turned away. “The spirits have not asked for your life. Why ponder a demand that has not been asked?”

I hated him for that. Yes, although I loved him with all my heart, I despised him for those words.

Krika continued pleading for his life. Okiak aimed his vialka and let it fly through the sky toward his son. Krika’s wail sounded over the fields and the low-hanging willows and past the Great Salt Desert. But no one spoke for him, not my father, not the other shaman, and not the Creator. He died, battered beneath a hail of stones; all eyes but mine witnessed his last breath. Father had pulled my face into his chest, and I hated my weakness for allowing it. My tears soaked his tunic. He gently stroked my head and played with my braid, and told me that I should forget, forget, forget, for death—however it comes—is the destiny of all men.

They left Krika’s body where it fell. Unburied, he was to be devoured by wild wolves and bears. Worse, his lack of a burial meant he could not enter the fields we long for. He could not hunt with the Creator. His father had damned him to everlasting grief.

Krika had been my age-brother, taught with Prince Lihu as I was. While he lived, his presence colored my life as a wolf’s continuous howl or a woman’s singing might color the night. He seemed to rage against the spirits while yet singing to the Creator. This was a strange thing, for at that time no one in the three tribes sought the Creator; we thought those shadow gods were his servants. Even I, who was suspicious of the spirits from my birth, had never warred against them as Krika had.

That night, as the sun set over my father’s Golden House, I escaped to the shrine. There lay Krika, broken on the ground. With many shuwas, I warded off the wolves and lions that had sniffed out my friend’s blood. But the spirits fought against me, calling from the east, west, north and south, all creatures of earth and air. How black the field and night sky grew with their descending shadows. In the field, only two men: Krika and I, one living and one dead. All my father’s so-called Valiant Men were nowhere to be seen. Although they had battled mightily against the Angleni, on the night of Krika’s death they hid in the compound trembling in fear of the spirits.

Then, all at once, I understood the spirits had arrayed themselves in battle against me, that I would always battle them alone, for I had no ally ... no, not one among my clan.

SATHA: Sowing Moon—First Cool Moon

In those days, I could not sleep, for grief had rolled into grief: a dear cousin slain, a sister kidnapped, our clan destroyed and scattered. The last sorrow—a harrowing journey to a far region where comfort of family and friend could not be found—was the worst of all. My mother changed, growing more sullen than before. She wept continually, crying aloud and begging the Good Maker to roll back time and to bring back her lost youth, her lost fortune, lost clan, and stolen child. So as I paced outside the college courtyard, listening to the songs of the young men inside, I could not help but be overwhelmed with grief.

Many young warriors had died during the forty-year war, and as the songs floated upward and away from me, I imagined their lives also flying away from us. Because of the war, I had not had the privilege of education. I had not studied the dead languages, as one should. Born to wealth but reared in poverty, I did not long for what I did not have. But often I found myself wondering about my lost education. Which language is being sung? I wondered now. Paetan or Seythof? What are the words of the song? As I pondered this, Mam raced up to me.

“What are you doing here, Satha?” She peered out at the marketplace. “Didn’t I tell you to meet me in front of the sword seller’s shop? Standing here, listening to men sing the day before the Rose Moon, a day when love is on the minds of all! People will say Monua’s daughter is so poor and lonely, she went searching for a man.”

The college lay on the western arc, opposite the Rock Gate and a stone’s throw from the sword seller’s shop. I gestured toward the courtyard wall. “I heard the collegians, so I came closer to hear the song. Do you think Father can tell me what this song means? Do you think they’re singing about the Angleni wars?”

“The Angleni!” She spat out the invaders’ names with such venom I feared the afternoon would be filled with her recounting of bitter memories. “I don’t want to hear about them, even in songs bewailing their cruel deeds. Come, hurry to the sword shop.”

“But Father doesn’t trade swords. Why should we—”

She glanced back over her shoulder as we sped along. “You’re asking too many questions, Satha. Hurry! We have little time.”

“Why should not I ask? You ordered me here and then took so long getting here—” I noticed newly applied kohl around her eyes. She had changed her kaba too. The kaba she had changed into was torn and ragged along the hem, far worse than the one she had worn earlier. The gyuilta thrown over it had been relegated to the scrap heap. I understood then that she had determined to appear both lovely and destitute at the same time. This decision provoked even my curiosity—and I was not one who was naturally curious. I tried to ignore this wonder beside me fearing that asking questions would only drag me into affairs I wanted nothing to do with.

Her eyes busily