Copyright © 2015 by Steve Himmer.

All rights reserved.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission of the publisher. Please direct inquires to:

Ig Publishing

392 Clinton Avenue

Brooklyn, NY 11238

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Himmer, Steve.

Fram / Steve Himmer.

pages ; cm

ISBN 978-1-63246-001-1 (ebook)

1. Spouses--Fiction. 2. Quests (Expeditions)--Fiction. I. Title.

PS3608.I49F73 2015

813’.6--dc23

2014045365

To Sage

Everything is burning. What is burning?

—The Buddha

…everything happens but nothing goes on.

—Dominique Jullien

Contents

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Acknowledgments

1

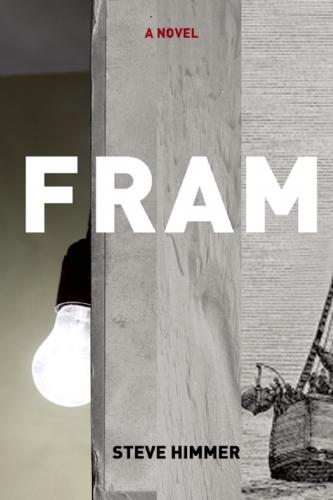

Rumor had it the lightbulb was already there when the Bureau of Ice Prognostication was founded at the height of the Cold War—the first one, the one that was actually cold, not the one with the bombs and Berlin Wall that came later. Oscar had held that line ready for years in case he was ever allowed to talk about what he did for a living.

That bulb had crackled and hissed through his years in BIP’s office, hanging from the same few inches of cloth-wrapped cord it had in the early days long before Oscar’s time. It persisted despite losing some luster, despite ancient filaments fraying and sizzling and threatening to snap. In winter it took longer to warm to a glow and on hot days in summer the bulb darkened so slowly it never quite dimmed overnight, their very own Arctic sun deep in the bureau’s basement domain. Without any windows, that varying light was the only sign of seasons passing. But the bulb reported for work every morning and had outlasted decades of prognosticators and their supervising directors. Policy stated it could not be replaced until it actually failed and heaven help the traitor who tapped at the glass or jerked the lamp’s chain or otherwise caused that noble, inspiring star to exhaust itself prematurely. Men above Oscar’s pay grade had been fired for less, for cursing the bulb when its light was too weak to get on with their work.

“Efficiency,” Director Lenz told Oscar and his partner Alexi in their weekly productivity lectures, first thing each Monday morning. “Efficiency and perseverance! That lightbulb can teach us all something about commitment and making do. You should spend a whole day—your own day, not ours, not for pay!—staring into that lightbulb to learn what it knows. Stare until you are blinded by its inspiration.”

Director Lenz could make anything sound like a slogan.

In Oscar’s first weeks at BIP, at his first productivity lectures, he’d nodded along vigorously. But after noticing the scant attention paid by Slotkin, his partner then, he realized how little it mattered to the director if his subordinates listened at all. So he aped Slotkin’s slight motions, his minimal nods reminiscent of the bulb at sway on its cord and always in motion despite the absence of wind in the office. Stirred by warm air rising from humming computers and working bodies, perhaps, or the hot air of directors’ lectures still circling the basement with no way out.

Sometimes supervisors from other departments brought their own charges down, to stand under the lightbulb and deliver their own inspirational talks. Such visits required careful concealments to make the Bureau of Ice Prognostication look more like the Bureau of Informational Policies it was known as to everyone not in the know. Files and paperwork had to be hidden and the big map of the Arctic turned around on the wall to instead show a colorful hierarchy of interdepartmental and interagency color code schemes—the work BIP was publicly responsible for.

Whenever it happened, the anxiety of being colonized even for a few minutes hung on Oscar for days, a lingering feeling of someone looking over his shoulder, even though one of the first things he’d done at BIP was to drag his desk—it had been Wend’s desk until then, Slotkin’s previous partner—away from the wall to sit facing the door. Slotkin had assured him no one would mind because not even Director Lenz made his way down the hall more than one or two times per year and they rarely heard from him at all between Monday lectures unless he leaned on his intercom’s button by accident. Oscar had assured Alexi of the same thing, when his time came after Slotkin’s was up.

Other than those rare visits, it was easy to forget the world existed apart from themselves and their work, apart from the Arctic they explored daily from the privacy of a cinderblock cellar. The world shrank to a pair of prognosticators, working in twos per tradition, and the lightbulb above with that long history of its own. They were a trio as cut off for a few hours each day as the men of Franklin’s first expedition had been while crossing the Canadian wild, though without yet resorting to eating their shoes or each other. Oscar brought his lunch from home on most days and Alexi preferred to go out. Director Lenz’ eating habits were a mystery to them.

The bulb wasn’t bright but its wan glow was faithful and always enough by which to stare at the minimal map of the Arctic spread on their wall and to think about what should be there and what, perhaps, already was. Enough to make notations and to write reports and to file them for Director Lenz to inspect or not bother at the end of each day. Any more light risked reminding the prognosticators their basement room had no windows. Any more and they