DISCOVER INDONESIA

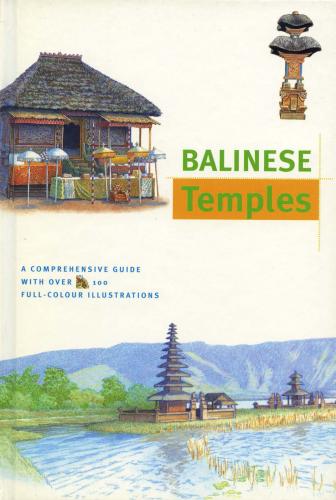

BALINESE

Temples

JULIAN DAVISON

& BRUCE GRANQUIST

Copyright © 1999 Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

All rights reserved

Printed in Singapore

ISBN: 978-1-4629-0705-2 (ebook)

Publisher: Eric M. Oey

Text: Julian Davison

Illustrations: Bruce Granquist, Mubinas Hanafi, Nengah Enu

Production: Mary Chia,Violet Wong & Agnes Tan

Distributors

Indonesia:

PT Wira Mandala Pustaka

(Java Books-Indonesia)

Jl. Rawa Gelam IV No. 9

Kawasan Industri Pulogadung

Jakarta 13930, Indonesia

Singapore and Malaysia:

Berkeley Books Pte. Ltd.

61 Tai Seng Avenue, #02-12 Singapore 534167

United States:

Tuttle Publishing USA

364 Innovation Drive

North Clarendon, VT 05759-9436

Tel 1 (802) 773 8930

Fax 1 (802) 773 6993

Contents

Of Gods and Men

Unlike their Indian counterparts, Balinese shrines and sanctuaries do no: generally include a physical representation of the deity to whom they are dedicated. There are, however, exceptions, as i the case of the Pura Penulisan, situated high on the crater walls surrounding Gunung Batur, where one finds this fine example of a stone lingga (below). In Hindu iconography, the lingga is a representation of the god Siwa, the phallic symbolism of the image being a celebration of the creative aspect of the deity. The veneration of the Hindu god Siwa plays an important role in Balinese religion, but lingga are usually found only in the oldest sanctuaries. Evidently the disappearance of a physical representation of the deity is something that happened after the introduction of Hinduism to Bali.

There are literally tens of thousands of temples and shrines on the island of Bali, a proliferation of religious architecture which probably is not equalled anywhere else in the world. Glimpsed through a screen of trees, or.across a swathe of verdant rice fields, the Balinese temple seems almost to be a part of the natural order of things. Closer to hand, the crumbling brick work and lichen-cohered statuary convey a sense of considerable antiquity, while the astonishing sculptural repertoire of demonic masks, multi-limbed deities and lurid depictions of sexuality that confront the Western eye, conjure up an exotic otherness of 'lost' civilisations and licentious natives—the 'Mysterious East' of all good Orientalist fantasies.

But Balinese temples need not be quite so mysterious if one takes an informed look at the underlying logic which determines the layout of the sanctuary and the symbolic significance of individual structures in the temple precincts.

Balinese Religion

The religion of Bali represents an eclectic blend of Hindu and Buddhist beliefs laid over a much older stratum of indigenous animism, and it is this combination of native and exotic influences which informs so much of Balinese life. The introduction of Indian religious beliefs to Southeast Asia began about the time of Christ and represents not so much a story of conquest and colonisation as one of cultural assimilation which followed in the wake of burgeoning trade links with the subcontinent. In the case of Bali, bronze edicts, written in Old Balinese, testify to the existence of an Indian-style court by the end of the 9th century, but Balinese Hinduism, as we know it today, owes more to East Javanese influences between the 14th and 16th centuries. The latter have subsequently been shaped by local traditions to create a singular form of Hinduism peculiar to the island.

Reincarnation and a Cosmic Order

Hinduism is founded on the assumption of a cosmic order which extends to every aspect of the universe right down to the very smallest particle. This organising principle, or dhama, manifests itself in the persona of the gods, while demonic figures represent agents of disorder and chaos. As far as man is concerned he must try to conduct himself in a manner which is in keeping with his own personal dharma, the ultimate aim here being to gain liberation (moksa) from the endless cycle of reincarnation or rebirth to