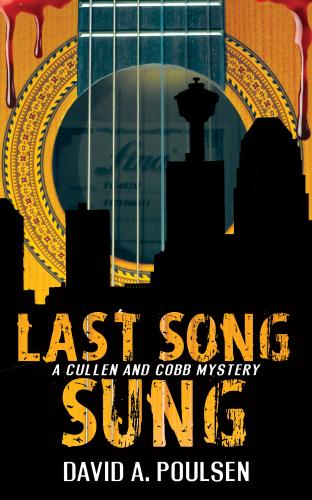

Cover

OTHER CULLEN AND COBB MYSTERIES

Serpents Rising

Dead Air

In memory of my dad,

Lawrence Allen (Larry) Poulsen,

who shared with me the joy of reading

In memory of Wayne Lucas,

who shared with me the joy of friendship

And always … for Barb

Prologue

February 28, 1965

The cigarette smoke stung her eyes. She threw the cigarette down, regretted it right away — hated to do that to a Lucky Strike, damn good smokes — and looked around.

Looking for Joni. Joni Anderson, who said she’d be there for the last set before taking the stage herself. But Joni wasn’t there. Not yet. Or at least not here in the alley, smoking, laughing, tuning her guitar in one of those crazy, brilliant, completely open-string, Joni-esque ways that few could follow, let alone play.

She rubbed her eyes, trying to drive the sting away, and squinted at the back of the building. Not old, not new, just one more building in a row of structures that offered no more or less than this one.

The Depression. She’d always felt it was a weird name for a folk club. First of all, people often mistakenly thought the name referred to the mood, not the social and economic shock that had devastated so many of the world’s economies in the 1930s. This Depression was that Depression; it had nothing to do with the state of mind. The old newspaper clippings that dotted the walls, virtually the only decorations to be found in the place, provided the proof as to which Depression was being referred to.

Instead of Joni, the only other people in the alley were her two band guys: Jerry Farkash, who’d been with her from the beginning twenty-one months ago, and Duke whatever-the-fuck his name was, surely to God the worst bass player to ever stride on stage with an Airline electric around his neck.

She glanced at her watch. 10:50. She’d begin her last set at 11:00. Joni would take the stage just after 11:30, play for an hour and a half with barely a break, and everyone would love her. Like they did every night.

She really wanted Joni to catch her last set. Especially the new song, the one she’d co-written with the shitty bass player. The guy could write lyrics. That was the only reason she’d kept him around this long. But even with his ability as a lyricist, she knew he’d have to go. He was killing them on stage.

And the guy was weird. What kind of name was Duke? And his last name was just as crazy. Prego, that was it. Prego. You’re welcome in Italian, for Christ’s sake. Not his real name, obviously. Who calls himself Duke You’re Welcome? The guy had to go, and before her Vancouver date at The Bunkhouse. She’d pay him something for the lyrics and then send him on his way. She’d rather play The Bunkhouse without a bass player than have Duke fucking Prego on that stage.

She looked at her watch again. Just time for one more Lucky Strike. She turned away from the biting wind to light it and didn’t see the car come up the alley. She heard it, though, and once her cigarette was lit, she turned to see if it was Joni. Maybe she’d caught a ride with some guy, or —

As she turned, she heard the screeching of brakes. The car doors were flung open. Then pop, pop, pop — not loud like you’d expect gunshots to be, but they were gunshots. She realized that when first Jerry, then Duke went down clutching his chest, groaning, then gasping like he was trying to get air. Then two men — one of them holding a gun — were racing toward her.

She tried to run, but it all happened so fast. There was one fleeting moment of recognition. A scream … a curse. Then the first man, not breaking stride, hit her with his fist, and it was all over.

One

There was something Holmesian about it.

Cobb and I were sitting in his office, drinking Keurig Starbucks, me looking out the window at 1st Street West below us and watching a beautiful twenty-something blonde cross the street and head toward Cobb’s building.

My memory told me that was how several Holmes stories began — except, of course, it was Holmes’s apartment on Baker Street that he and Watson were in and Holmes was either playing the violin or reading the newspaper. Cobb had spent the last hour invoicing clients and telling me in general terms the nature of their cases. To my knowledge, Cobb did not play the violin.

There was, however, a bit of a similarity between Watson and me. Although Holmes’s companion was a doctor and I had spent most of my adult life as a crime writer, first for the Calgary Herald and then as a freelancer for the last several years, the fact was that, like Watson, I was something of a chronicler of the cases Cobb and I had worked on together. I was, at that time, working on a couple of articles I hoped to shop to magazines — articles that recounted the details of our recent investigation into the violent deaths of a number of right-wing media luminaries. That was the reason my computer sat at the ready on a small table in one corner of Cobb’s second-floor space on the corner of 12th Avenue and 1st Street West in the Beltline, an elder statesman among Calgary neighbourhoods.

“You’re about to have company,” I said, not looking away from the street or the young woman, who had clearly favoured denim when she had made the day’s fashion decisions. I was confident of the correctness of my assertion because at the moment, Cobb was the lone tenant of the building, all the others having been temporarily evacuated while renovations were taking place. I’d asked him how it was that a private detective was not inconvenienced with having to vacate his office when other firms with more office space and several actual employees had been. Cobb had smiled as he told me that, as soon as the building manager had mentioned Cobb would have to leave the building for a couple of weeks, Cobb made as if to begin the packing process, pulled several firearms from his closet, and set them on his desk. The manager, apparently not certain whether the weapons were part of the move or had been taken from the closet for some other purpose, decided that Cobb’s office looked “okay as it is” and backed out the door with considerable dispatch.

“Male or female?” Cobb asked, without looking up from his own computer.

“Decidedly female,” I told him.

“And you know she’s coming here because …?”

“Because (a) there’s bugger all else on this side of the street, (b) she keeps looking up here as she gets closer, and (c) she’s now entering the front door of the building.”

“Ah … that last one’s a dead giveaway.”

He closed up his computer in an apparent attempt to look more detective-like for the new arrival and had just completed that task when the knock came at the door. I turned from the window, crossed the office, my slippery city shoes (as Ian Tyson called them) drumming on the aged hardwood, and opened the door. My closer look at the young woman confirmed what I had been fairly certain of from my window view of her. Though the September wind had done her mid-back-length blond hair no favours, she was striking. Young — twenty-ish, I guessed — and … striking.

“Is this the office of Michael Cobb, private detective?” she said in a voice that was breathy but firm. My first impression of her was that she was no-nonsense.

“It is,” I said, and stepped back to allow her to move into the office.

She stepped inside, and Cobb stood up to greet her. There was a momentary look of confusion on the young woman’s face as she looked from me to Cobb and back at me.

I gestured in Cobb’s direction to allay further confusion.

“I’m