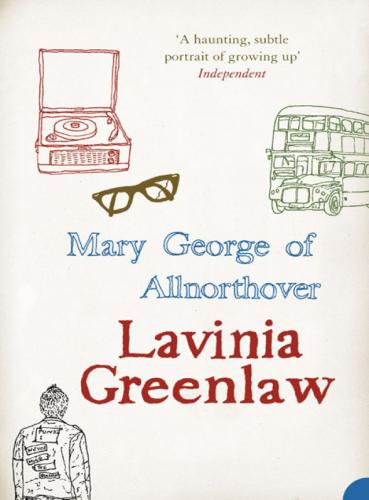

LAVINIA GREENLAW

Mary George of Allnorthover

for my daughter, Georgia, turning thirteen

The death of earth is to become water,and the death of water to become air,and of air, fire, and the reverse …

HERACLITUS

CONTENTS

On 28th June 197–, Mary George of Allnorthover was seen to walk on water. It has to be said that the only witness was Tom Hepple, who was mad and had been away from the village for ten years until he turned up that very day, shouting. Mary had always been thought of as a peculiar child, but not one to seek attention. She had neither grace nor mystery and could not have wanted to become Tom Hepple’s angel, especially not the restoring angel he was looking for.

The house that Mary George woke up in was not one she knew. It was part of a straggle of Victorian cottages leading down to the station in Crouchness, built quickly from cheap brick that had now vitrified. The walls resisted hammers and drills, shed plaster, spat out nails and picture hooks. The rooms were low and dark. The front door led, in two steps, to a squat staircase at the top of which were two bedrooms Mary never saw. She had slept in a corner of the living-room, which was sallow and square.

The night before had been someone’s party. There were half a dozen people on the floor around her, including the boy who had been holding her hand as he closed his eyes. The others lay at odd angles, not touching, bent to whatever space they had found between the slippery three-piece suite, upon which nobody had attempted to rest, and the smoked-glass coffee-table. Where the shaggy carpet had been scorched, its nylon thread was gluey and fused. The floor was scattered with crumpled cans and plastic cups half full of dog-ends and vinegary dregs. There was a bowl of cornflakes someone must have thought they wanted.

Mary sat up and reached into the bag she had used for a pillow. The right lens of her glasses was cracked but she put them on anyway, and moved towards the boy. He lay on his front, sweating gently inside what might have been his grandfather’s pinstripe suit. Mary crouched over him, her left eye squinting behind the one good lens. He had pulled up his right leg and stretched his right arm forward. As if swimming or flying, she thought. Mary studied the bones of his wrist and ankle, exposed by the too-short suit. His long fingers had a delicacy at odds with their large, rough knuckles.

The boy’s hair was thick and wavy, both dark and fair. It was brown where it was shaved high at the back of his neck and blond in the matted fringe that obscured most of his face. He was flushed and open-mouthed. Mary concentrated hard and, steadying her glasses with one hand, moved the other towards his cracked lips. In the sour still air of the room, the rush of his breath startled her. She lost her balance and fell back, knocking over a tower of beer cans. Their clatter was surprisingly dull and Mary had stuffed her glasses in her pocket and left before anyone else had properly opened their eyes.

Crouchness sat on the point of the estuary where clay gave way to mud. It was the first or last stop on the London line, a town built on fishing and coastal trade, now propped up by light industry – packaging, canning and printing. The clapboard sail-lofts perched on stilts along the shore were empty, too high to live in and too draughty to use as stores. The locals had been expert sailors in these shallow waters. They had known how to navigate the narrow passages between the sandbars that riddled the low-lying east coast. They had hauled in so much herring, some had been barrelled, salted and exported to Russia. In the summer they had crewed on yachts, their local knowledge keeping the gentry from getting stranded. They had earned enough to buy their own homes.

There were boats still, a handful of dinghys owned by local lawyers and doctors, a couple of dredgers and a light-ship that had become obsolete five years ago and was left moored in the docks, a heavy-bottomed ark slumped in the mud at low tide.

Mary walked down to the shore and out along a path on top of the dike. The ground here was neither earth nor mud, but something in between, greasy, compacted and dark. It was five o’clock in the morning, bright and warm in a tired, dusty way like the end of a hot day rather than the beginning. Soon, this heat would concentrate itself once again and people would get out of bed to open windows that were already open.

Mary had slept in all her clothes: a heavy ink-blue twenty-year-old dress and a stringy dark-red cardigan she had knitted out of synthetic mohair on the biggest needles she could find. It had no buttons and so she habitually clutched its edges together in her fist. She pulled the cardigan off and stuffed it in her bag, an army-surplus knapsack with a slipping strap. It came loose and banged around her knees as she walked. Her feet sweltered in heavy boots. She tried wearing her glasses again but seeing the cracked path and wilted grass made her feel even hotter, so she put them away. Squinting back inland, Mary could not tell the creeks and the banks apart, they ran in and out of one another so and nothing shone in a way that suggested water. The town was a blur of grey, like a model waiting to be painted. It had long been stripped of its colour by salt and the winds that blew in ‘straight from Siberia’, as everyone said, not wanting to think such icy cold could be local.

The mud gave off a stink of burning tyres, ammonia, diesel and harshly treated sewage, nothing natural. What life there was, was amorphous, useless: lugworms and silted shrimp. Further up where the coast broadened out into the sea and the edge of dry land was definable, there were lobsters, samphire and crab. Boats put out to sea and did battle with Icelandic fishermen over cod. That was where people went to open their lungs. Crouchness had the only kind of sea air Mary really knew and she tried hard not to breathe it.

It was almost six o’clock. Mary turned back towards the town, hoping for the milk train. When she got to the top of the station road, she found she