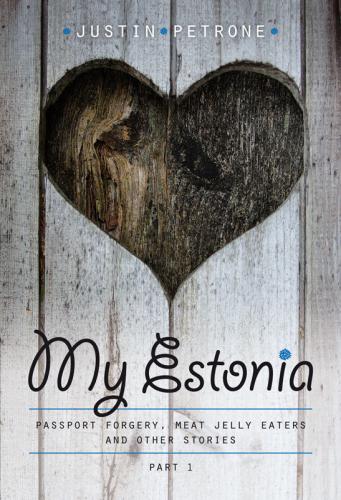

My Estonia

A MOMENT IN ZAVOOD

I met Epp in Helsinki. Usually when Estonian ladies ask where we met – and only ladies ask – they respond with interest in this fact. “Helsinki!?” they say in surprise. “Why, what were you doing there?”

Could Helsinki really seem so distant to some Estonians? Were they really that local in their mindset? All one had to do is take a ferry north from the capital of Estonia, Tallinn and they’d be in the Finnish capital, Helsinki, surrounded by moi1 and moi moi2. Other foreigners must have been lured to Estonia by its womanhood via this route. Other foreigners like me.

Having met Epp in Helsinki has allowed me to extract myself from some awkward conversations. Once in Zavood, the basement-level bar that stays open the latest in the Estonian university town of Tartu, two muscular, sweaty, blondhaired townies – let’s call them Hardo and Janar – decided to make something of the fact that I had stolen “their” table, where their empty beer glasses had stood for 5 minutes or more.

“This is our fucking table,” swore Hardo, clearly looking for an excuse to hit somebody, anybody. In the background, young co-eds played pool and sipped beer. The cacophonous sounds of a local rock band blasted from the speakers.

“I’m so sorry,” I replied nervously, in Estonian. “I thought that this table was free.”

“You have a weird accent,” said Janar, who also seemed itching to punch somebody. “Where are you from?” he demanded. Janar’s heavy hands were covered in dark marks, perhaps from fixing bicycles or car engines. Or strangling people.

“I’m from New York,” I said, quickly moving to explain my situation, “but my wife is Estonian, so I can speak Estonian.”

“Your wife is Estonian?” Hardo exploded in jealousy. He clearly didn’t have his own eesti naine3. Hardo looked at Janar as if this fact – a foreigner making off with one of their women – was enough to try and convict me in the name of southern Estonian justice. Not only had I stolen their table; I had stolen one of their women as well.

To Hardo and Janar, I was surely just another undeserving wealthy foreign man who had decided to take an Estonian girl as a trophy wife. When it came to women, multicultural marriages always moved West. Finns, Brits, Dutch, and Americans married Estonian girls, while Estonian guys settled down with Russians or Ukrainians. Or so I had heard.

“Yeah, but don’t worry, guys – we actually met in Helsinki,” I explained in a calm voice.

“Helsinki?” they looked at each other in curiosity. “What would a nice Estonian girl be doing in such a faraway place?” Janar asked.

I thought he was kidding. But then I realized that, for a lot of Estonians, Helsinki – only 80 miles from Tallinn – was some far-off metropolis. Anyway, Janar and Hardo suddenly calmed. Two minutes later we were deep into a conversation about the challenges of learning the Estonian language.

“Do you know,” Hardo admitted as we sipped our beers, “that you speak Estonian really well.”

Janar agreed. “There are people who have lived here for fifty years,” he gestured with his meaty fists, “and they don’t even know one word!” In the sweaty air of Zavood’s underground bar, I blushed from the compliment, even though I had heard it a few times before.

However, Janar and Hardo had understood that I did not come to their land with the specific intent to make off with one of their women. The first time I had come to Estonia, it was only supposed to be for one day.

Tartu, July 2009

PS. While most of the names used in this book are genuine, some have been changed to respect the privacy of certain individuals. All the events, though, are true to the best of my recollection.

HELSINKI IS NOT ROMANTIC

Helsinki is not romantic. For most people the ferry docks in the Finnish capital do not evoke the sensual feelings of the Mediterranean.

Yet whenever I find myself anywhere near the Esplanaadi – the long walking street that terminates in a fresh food market near the ferries that go to Tallinn – I am overcome. It was here that I met Epp for the very first time.

I had stood there one gorgeous August day, my body pummeled by jetlag, staring at this young Estonian woman and her mane of curly hair. She wore red pants, a red corduroy jacket, and orange tinted sunglasses. The little waves of the Gulf of Finland lapped the docks, and Epp had stood there smiling in the sunlight, set against a backdrop of happy-looking ships and people selling fresh fish.

“My name is Epp and I am 28,” Epp said, approaching me. “I just got back from India. It’s so weird to see the Baltic Sea again.”

I nodded and introduced myself. Justin, from the United States, aged 22, glad to be far away from home. Glad to be far away from anything. I listened as Epp spoke, and watched her hair flapping in the wind. I watched her smooth tanned body, lithe fingers, and high cheekbones.

Then from somewhere in my body, a tiny voice commanded me to make babies with her – sorry, Janar and Hardo. I instantly felt vulnerable. “Shut up,” I told the little voice. “Whatever you do, don’t get me into any more trouble.”

After my eight-hour plane ride, Epp to me might as well have been some Baltic aphrodite. I couldn’t hold a conversation because I was so tired and delirious. From time to time, it literally seemed as if my vision would wrinkle from fatigue. Supposedly, it was 2 pm here on the docks, but it might as well have been 7 am or 9 pm or 25 o’clock. My body didn’t know what time it was anymore.

And I didn’t know what to expect from Finland, but I knew instinctively that coming here would be an emotional milestone. I was thousands of miles away from most of the people I knew and yet, for some reason, I didn’t miss them. I had watched already as people in our international program had scurried like rats to the Internet cafes to e-mail friends at home. But I sent no messages to my friends, and I only used a pay phone one time to let my mother and father know I was still alive.

I wanted to be detached. I wanted to disconnect. I wanted to be here in Helsinki. I needed to replenish my soul, I told myself, given all the messed up things that had happened in the past year. And the replenishment of one’s soul did not include romantic intrigues with anyone, not even Epp and her red pants.

Besides, I came to Helsinki not for love, but because I was in the Finnish foreign correspondents’ program. I had been searching for a job online during my last semester of university in Washington, DC, and I found Finland instead. I rattled off an essay about my desire to see the northern lights, and managed to impress the interviewer at the ultramodern Finnish embassy enough that I was one of two Americans selected to go. Maybe the interviewer had sensed how desperate I was when she met me.

My life, by that point, had turned into something resembling The Real World, an American TV series that followed the messy personal lives of individualist twenty-somethings as they tried to find themselves against a threatening urban backdrop of nihilism and sexually-transmitted diseases.

My college romance had burned out in a maelstrom of infidelity and emotional upheaval. As much as I had loved her, the garden of love we tended had been mowed down and salted so that nothing could ever grow again. To kill the pain I fell in with ne’er do well bohemians, who ate hashish like candy. Why, some of them even mixed it in their food every night.

They were on the same sad carnival ride to nowhere as I, and no doubt as deeply miserable. Misery does love company. And what was it that that some girl had said to me at a party one night? She said that I had no ambition and she was right. In hindsight, Finland really was my last hope. It was calling me in my sleep from Helsinki: an open-air mental institution on the other side of the world.

Our program, organized by the Finnish foreign ministry, had basically one objective: to entice promising foreign journalists to Finland, brainwash them about how great Finland was, and then send them back to their home countries, where someday, when they became heads of